The Vampire

The first film released by the Gardner, Laven, and Levy production team remains one of the better 'B' films of the 1950s. 1 HR 15 MINS 1957 United Artists

HORROR/SCIENCE FICTION

by Gary Svehla

1/13/202611 min read

Story

Just another house in a settled neighborhood, with a kid on a bike delivering an animal to Dr. Matthew Campbell (Wood Romoff). The teenager finds the doctor in distress, face down on his desk, begging for help. He tells the boy to get Dr. Beecher right away.

Dr. John Beecher (John Beal) arrives and finds Dr. Campbell in the same condition. Beecher helps Campbell to his couch, where Campbell talks about dying and about his experiments proving true. Campbell hands Beecher a bottle of pills, telling him to hold them. Then Campbell slumps and dies.

George Ryan (Herb Vigran), Police Sergeant, is speaking with Sheriff Buck Donnelly (Kenneth Tobey) when Dr. Beechen enters the office. Beechen brings Matt Campbell’s medical report to the sheriff, telling Buck that Campbell died from “a simple coronary.” Dr. Beaumont (Dabbs Greer) is being called down from the university to take over Campbell's position.

Dr. Paul Beecher returns home, greeted by his young daughter, Betsy (Lydia Reed). The doctor complains to his nurse about another headache and asks Betsy to fetch his migraine pills from his coat pocket. Beecher is seeing his next patient, Marion Wilkins (Ann Staunton), who is worried about living alone with a heart condition. Beecher abruptly rises, squirms in pain, and puts a hand to his head, telling Marion he’ll see her tomorrow morning.

The next morning, Sheriff Buck Donnelly goes to Dr. Beecher’s office. Buck warns Paul of a prowler in the neighborhood. The housekeeper reports that Marion Wilkins is terribly ill, and Beecher says he’ll be right over. Dr. Beecher says her heart is acting up and asks the cleaning woman to call an ambulance. Marion lapses in and out of consciousness, telling the doctor to go away, “Leave me alone! Don’t touch me!” From exertion and fear, Marion apparently suffers a fatal heart attack and dies. The doctor observes two bite marks on her neck. While speaking to Carol (Coleen Gray), he pulls two vials of pills from his coat pockets and is perplexed about whether he really took his migraine pills.

Dr. Beecher goes to Campbell’s home/lab and finds all the animals dead in their cages, except for the bats. At that moment, Dr. Beaumont arrives with his assistant, Henry Winston (James Griffith), who will eventually take over Campbell’s job. Beecher warmly welcomes his old friend. Beecher asks Beaumont what Campbell was researching. Beaumont answers, “We’ve been subsidizing scientists to work on regression to see whether it’s possible chemically to revert the animal mind to a primitive state. And if it is, whether we can reverse the process and advance human intellect … He claimed he developed a pill … They’re supposed to induce these primitive instincts by temporarily draining the blood from the brain.” Beecher is concerned he may have taken some of these pills by accident. Beaumont adds, “But apparently it doesn’t harm the animals as long as they keep getting the pills. You see, they’re habit-forming.” Beaumont says Campbell told him that if the animals don’t get the pills every 24 hours, they go wild.

Returning home, Paul Beecher finds his daughter practicing dance to recorded music. Paul is even more agitated and tells Betsy to turn it off and go to bed, when she is only trying to make him watch what she has learned. Paul rushes into his bedroom and grabs the bottle of pills. He hesitates to take one and falls on his bed exhausted. At 11 o’clock, Betsy awakens. She goes to check in on her father, knocking on his bedroom door. But Betsy never sees that the bedroom window is open and Paul is gone.

Henry is still working in Campbell’s lab as a thunderstorm rages. Beaumont phones him, and Henry says he is starting a chemical analysis of the pills. Suddenly, the lights in the lab go out. Henry tells Beaumont, “Doctor, I think the pills are a control serum … from the bats. They were the only animals immune.” A beast lurking around the shadowy lab suddenly attacks Henry. The next morning, Henry is found dead by Buck. Beecher arrives. He quickly examines the body. He tells Buck about the bites on Henry’s neck, the same wound Marion also had. Beecher soon notices that all the bats are gone from the lab.

Walking the streets and warmly greeted by patients, Dr. Beecher appears almost comatose, ignoring them and momentarily thinking of turning himself in to the police. Buck tells Willie, the mortician, that he plans to exhume Marion’s body. Beecher implores Carol to cancel her date with Buck and stay to watch over him. He tells the nurse he has been depending on his migraine pills and that, if she’s around, he might not take them.

At the Hideaway Supper Club, Paul and Carol are enjoying the revelry at a table, but a telephone call brings him back to reality. He is called away to perform an emergency abdominal, and the resident is awaiting him. Before leaving, he drops Carol’s purse to retrieve his pills, which she is holding. He asks Carol to wait for him here.

At the hospital where the surgery is underway, Dr. Beecher seems fixated on taking another pill, jittery and unfocused. The doctor almost blacks out. Somehow, Beecher completes the surgery, surprising his medical team. Before closing the incisions, Beecher abruptly leaves to call Carol, but she has already left the restaurant to go home.

Meanwhile, Buck and his team open Marion’s casket and discover primary decomposition that shouldn’t have progressed this far. They even consider the possibility that they may have opened the wrong grave, but a quick check confirms it is Marion Wilkens's grave.

Carol walks home on neighborhood streets in the dark. She encounters Mrs. Dietz (Helen Hill), who is walking her dog, Priscilla, and says she needs more exercise. Carol continues walking as crickets chirp. All at once, Carol hears footsteps behind her. She looks back and sees nothing. But when she looks again, she sees a man following her. They both start running, but Carol reaches her house and goes inside before the fiend can reach her.

Meanwhile, Mrs. Dietz cheerfully walks with Priscilla, but the dog looks back in fear. The dog barks, upsetting the elderly woman. From the dark, a fierce beast lurches toward her as the dog runs for safety. The shadowy fiend continues his attack on the woman. Neighbors run out of their houses to help Mrs. Dietz, but it is too late. The gyrating fiend watches from a distance.

Beecher groggily awakens the next morning, fully dressed on his bed, looking worried and calling Carol to see whether she’s safe. Carol tells Paul about the violent death of Carrie Dietz. When Carol says he tried to get to me first, Paul’s face turns to absolute horror. He realizes he is the town’s monster, with no memories of the preceding nights, and unable to control his actions. He buries his face in his hands. He tells Betsy he wants her to live with Aunt Sally for a while.

Beecher is alone in Campbell’s lab when Beaumont enters. Beecher confesses to killing Carrie Dietz last night; Paul’s confession clearly confuses Beaumont. Beecher continues, “I don’t know how. I don’t even remember doing it, but I’m sure I killed her. And I think I killed Henry, too, and Marion Wilkins. I know it has something to do with those pills of Campbell’s. I started taking them by mistake.” Will tries to suggest the pills may have abetted his emotional state, but Will cautions Beecher not to ruin his career. He says he’ll stay with him to make sure he does not take the pills.

Buck is checking with the medical examiner, who says the fiend extracts a small amount of blood from his victims’ throats, but because he carries the virus in his saliva, he contaminates them. However, he remains immune to the virus. The examiner says he has never seen such total cellular destruction.

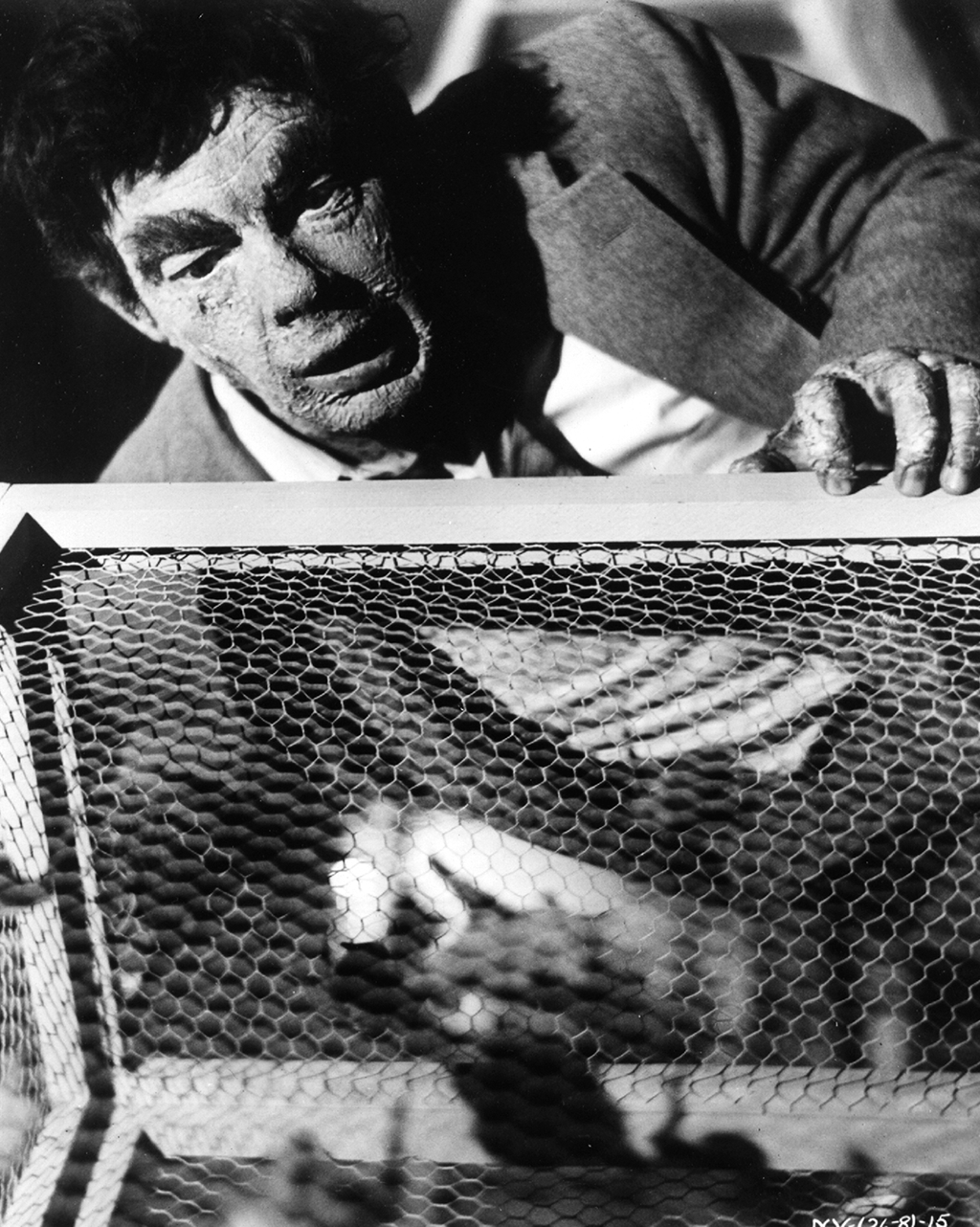

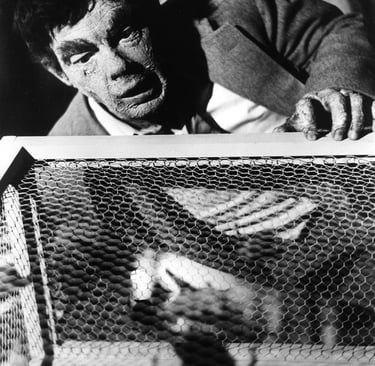

Will asks Paul for his pills, and Paul hesitates. Will locks all the pills in a desk drawer. Paul, seriously addicted, bangs on the drawer to reach his pills. Will prepares to administer a sedative. Paul lays his head on the wooden desk, moaning in pain. Will readies the sedative, but before administering it, he witnesses Paul’s hand turn into something bestial. Then his face transforms. Slowly, Paul rises, stalking and killing Beaumont. Then he burns the body in the lab furnace.

Buck receives the final report on the blood cells from the university, and reminds Buck that Matt Campbell had been working on a rare virus that causes capillary disintegration. Buck, perplexed, asks about Will Beaumont. “Do you think he’d go so far as to do a little experimenting on human beings?” Buck and Sgt. George Ryan return to Campbell’s lab to find the furnace blazing and Beaumont absent. Accidentally, they turn on a recording device that captured the final moments of Beaumont’s life during the attack.

Looking grim, the cops rush to Beecher’s office, but Carol is already inside, far ahead of them. Paul looks messy and mentally chaotic. He tells the nurse to go home, saying he hasn’t scheduled any patients. Paul’s hands begin to transform. He punches Carol to protect her as the final transformation completes. As Carol revives on the floor, she sees the monster before her. Paul stalks her as she flees, and the squad car pulls up to the house. Buck and George break into the locked house. Carol flees outside, closely pursued by the vampire beast. Paul hides in the brush, attacking Buck as he passes. Struggling with the fiend, George finally fires three shots into the monster, killing Paul, who reverts to human form.

Critique

The production team of Arthur Gardner, Arnold Laven, and Jules V. Levy created four horror films during the 1950s: The Vampire (1957), The Monster That Challenged the World (1957), The Flame Barrier (1958), and Return of Dracula (1958), before making a Western and turning their attention to television production. The films were all written by Pat Fielder, except for The Flame Barrier, which George Worthing Yates co-wrote. Pat Fielder was one of a few female “B” horror-film writers, and her screenplays were original and frightening. Fielder was a UCLA Theater Arts Department graduate. Three of the films were moderately successful, except for The Flame Barrier, which was co-featured with The Return of Dracula and was terrible.

The Vampire, the production team’s first feature, was one of the better “B” productions of the 1950s, one I continually enjoy. But why does this feature stand out above most of the other double-feature productions presented during the 1950s?

For one thing, this movie brought the vampire film into the modern era, forgoing the supernatural in favor of science. Vampires no longer produce other vampires, lie in coffins, or die only by a stake through the heart. They can walk in bright daylight and see their reflection in the mirror. In this feature, we are told that vampires extract only a small amount of blood from victims, infecting prey with saliva that carries an organ-destroying virus. A pill Matt Campbell discovered reverts the ingestor to a primitive, bestial state, is addictive, and forces that person to ingest even more drugs. The film is closer to being a Jekyll/Hyde picture than an actual vampire film. Not one hint of the Undead remains, but the vampire in this feature film is updated for younger audiences.

Another success of the film is its bevy of solid performances, including star John Beal. Dr. Beecher is a typical small-town doctor and surgeon who makes house calls and allows needy patients to defer payment until they can afford the bills. As a single parent, he always has time for his daughter, Betsy, and is the kind of good friend everyone knows wherever he goes. He may be the town’s most beloved citizen. So when he becomes addicted to the regression pills, few would suspect him of being the town’s prowler/murderer. Except he has one major problem: he was around 46 years old when he made this movie. Gardner, Laven, and Levy had the habit of hiring aging actors who probably worked cheaply. Kenneth Tobey was brought in to be the love interest for Coleen Gray, since it would be awkward for John Beal to be the love interest. But Beal’s distinction between being the town’s most beloved citizen and being a drug addict/monster was performed with cleverness.

Also, in his sequence examining Marion Wilkens in bed, as she thrashes around and ultimately dies, John Beal’s guilt over not helping her last night is palpable. His guilt about his addiction and his inability to remember his nights seem so real and horrific, adding another layer to the performance.

Lydia Reed's performance as Betsy Beecher's daughter adds depth to John Beal's performance, making him even more of a sympathetic lead. Being a single parent and finding time for his daughter shows how much love exists between them. But Gardner, Laven, and Levy had a child play a crucial sympathetic character in their next film, The Monster that Challenged the World, where she accidentally revives the sea monster by raising the temperature of the tank water, putting people at risk, just as Betsy put her father at risk by giving him the regression pills accidentally.

Director Paul Landres confidently imagined and handled the horror sequences, whether it’s the scene in which the beast pursues Coleen Gray down a neighborhood street, with her looking back to see the shadowy, undefined fiend in noirish blacks and whites, or Will Beaumont staying with Beecher in the lab to make sure he doesn’t take any more of the regression pills. His addictive personality makes him beg and quiver for more pills, as he slowly transforms into a primitive monster without taking any more drugs. Priscilla the dog’s performance, as she flees in fear for her life while the beast jumps out of the darkness to kill Mrs. Dietz, is wonderfully conceived. Landres is adequate with the actors’ dialogue, but he is gifted at blocking the horror sequences. His use of shadow and horror is masterful. Perhaps we should also credit cinematographer Jack MacKenzie.

Also adding to the chills is Gerald Fries’ dynamic score, which masterfully swells at precisely the right moments. He is the bold craftsman who knows when quiet intensity is required, when to crescendo, and when bombast is necessary. His score complements Landre’s direction.

And John Beal, who actually plays the monster (except for his death scene, in which the beast dies in the mud and a stand-in is used), adds panache to the performance again. Instead of simply wearing the monster’s makeup, John Beal seems able to droop his face, roll his eyes, and twitch at the same time. Instead of leering at his victims, he seems dumbfounded by them. Unlike most 1950s films that keep the monster in the shadows until the climax, John Beal’s beast is revealed pretty early in the production. And the innovative makeup holds up to greater exposure.

As previously mentioned, Past Fielder’s story and screenplay are full of emotion and heart. Her pacing is action-packed, avoiding most of the quieter moments that doom most programmers of the era. Her story never allows the audience to lose interest or become distracted. Whether it is fear or the sense that our doctor is losing control of his life, something meaningful is always happening to draw attention.

The Vampire holds up to repeated viewings and reexamination. Its monster is unique; John Beal's performance is committed and multilayered, remaining surprisingly complex for a “B” picture. All aspects of this low-budget production are solid. It’s one of the rare programmers that seem to rise above most others and still impress almost 70 years after it was made. While communism, women’s empowerment, sexual identity, racism, and the feared Other raged outside, these idealistic small towns throughout America were increasingly invaded by the problems of modern society. Films such as The Vampire illustrated that the comfortable, small-town America wouldn’t reign forever.

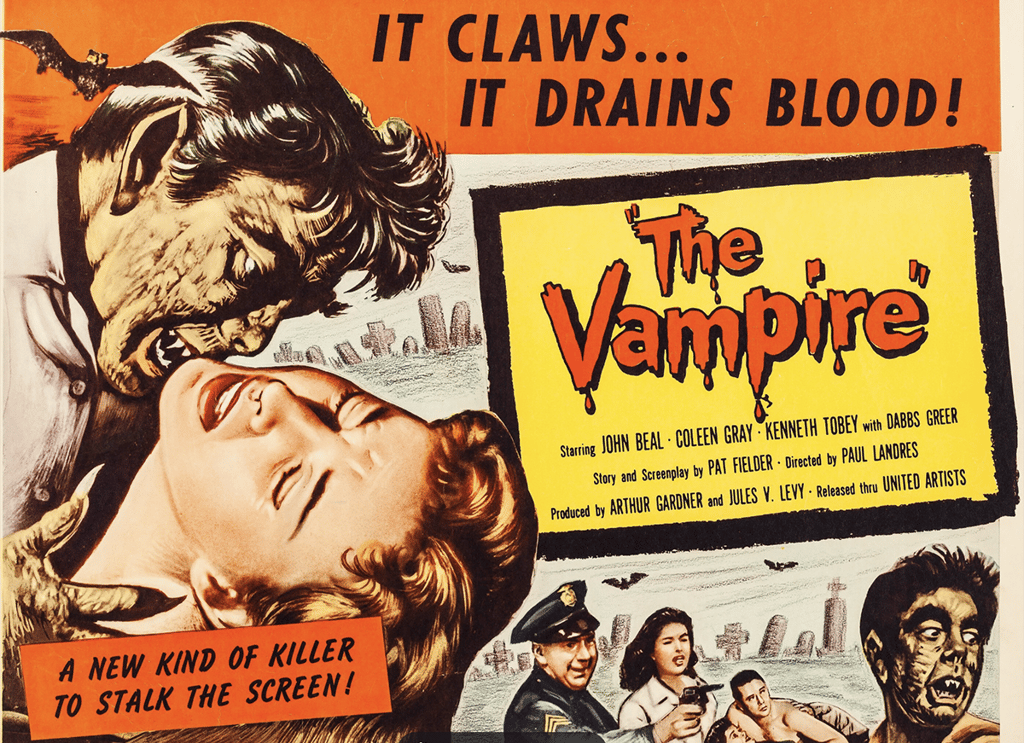

A PUBLICITY SHOT OF THE VAMPIRE BEAST AND FEMALE VICTIM

THE VAMPIRE IN A PUBLICITY SHOT CONFRONTING A CAGE OF VAMPIRE BATS.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com