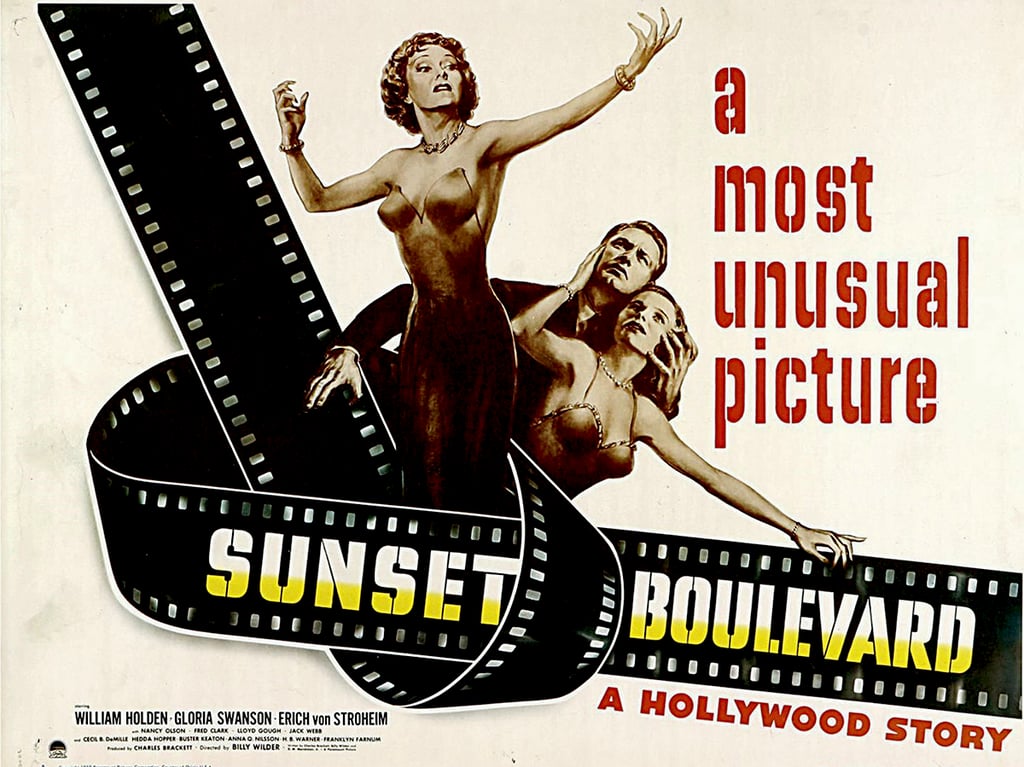

Sunset Boulevard: The Dark Side of Hollywood

One of the greatest films of dark cinema, Gloria Swanson's portrayal of an aging and forgotten silent film star morphs into a study of obsession, manipulation, and insanity. 1 HR AND 50 MINS 1950 Paramount

FILM NOIR/DARK CINEMA

written by Gary Svehla

8/26/202520 min read

The transparent Paramount logo shows a sidewalk with “Sunset Blvd” painted on the curbside as the camera pans downward, accompanied by rousing dramatic music by Franz Waxman. As the music continues, the camera moves further down the street while credits roll. After these credits, we hear sirens from emergency vehicles speeding along the same road. A voice narrates: “Yes, this is Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, California. It’s about five o’clock in the morning. That’s the homicide squad, complete with detectives and newspapermen. A murder has been reported in one of those great big houses in the ten thousand block. You’ll read about it in the late editions, I’m sure. You’ll get it over your radio, see it on television. Because an old-time star is involved, one of the biggest. But before you hear it all distorted and blown out of proportion, before those Hollywood columnists get their hands on it, maybe you’d like to hear the facts, the whole truth. If so, you’d come to the right party. You see, the body of a young man was found floating in the pool of her mansion with two shots in his back and one in his stomach. Nobody important, really, just a movie writer with a couple of B pictures to his credit. The poor dope, he always wanted a pool. In the end, he got himself a pool, but the price turned out to be a little high. Let’s go back about six months to the time of day when it all started. I was living in an apartment house above Franklin. Things were tough at the moment. I hadn’t worked in a studio for a long time. So I sat there grinding out original stories, two a week. Only I seem to have lost my touch. Maybe they weren’t original enough. Maybe they were too original. All I know is, they didn’t sell.” During this narration, the police drive up to a mansion and find Joe Gillis (William Holden) lying face down, dead in the pool. When we return to the past, the same Joe Gillis is typing away, seated on his bed in a robe.

As Gillis types, the doorbell rings, and two repo men ask where the car is. Gillis is three payments behind. “Well, I needed about $290, and I needed it real quick or else I’d lose my car. It wasn’t in Palm Springs, and it wasn’t in the garage; I was way ahead of the finance company.” Indeed, the car was parked across the street in Rudy’s parking lot.

“I had an original story kicking around Paramount. My agent told me it was dead as a door nail. But I knew a bigshot over there who always liked me. The time has come to take a little advantage of me. His name was Sheldrake (Fred Clark); he was a smart producer with a set of ulcers to prove it. Gillis tries to sell his baseball scenario to Sheldrake, saying Alan Ladd would be perfect for it, and that it could be made for under a million. A woman rushes into the office, saying the baseball story was written for “hunger,” a rehash of an older story, and Sheldrake says you can meet the writer, right here in the office. The woman’s face takes on an embarrassed look. She introduces herself to Gillis as Betty Schaefer (Nancy Olson). “Right now, I wish I could crawl into a hole and pull it in after me.” Gillis responds, “If I could be of any help.” Betty says she did not find it “any good, that it was flat and trite.” Betty exits the room, and Gillis asks for any type of job, writing additional dialogue, or anything. He even asks for a $300 loan.

“After that, I drove down to headquarters, that’s the way a lot of us think about Schwab’s drugstore, kinda a combination office, coffee glatch, and waiting room. Waiting, waiting for the gravy train. I got myself 10 nickels and started sending out a general SOS. Couldn’t get hold of my agent, naturally. So then I called a pal of mine, Artie Green (Jack Webb), an awful nice guy and assistant director. He could let me have 20, but 20 wouldn’t do. Then I talked to a couple of yes men at Metro. To me, they said no. Finally, I located that agent of mine, the big faker. Was he out digging up a job for poor Joe Gillis?” No, he was playing golf. “ So you need $300. Of course, I could give you $300, only I’m not going to,” Marino (Lloyd Gough) says, saying Gillis’ creative juices flow better when he is in need of money. But Gillis interjects, "It's my car; losing it is like having two legs cut off.” “Now you’ll have to sit behind a typewriter, now you’ll have to write!” Marino emphasizes. Gillis walks away in disgust.

As I drove back toward town, I took stock of my prospects. They now added up to exactly zero. Apparently, I just didn’t have what it takes. The time had come to wrap up the Hollywood deal and go home. Maybe if I hocked all my junk, it would be enough for a bus ticket back to Ohio. Back to that $35-a-week job behind the copy desk at the Dayton Evening Post, if it was still open. Back to the smirking delight of the whole office. Okay, you wise guys, why don’t you take a crack at Hollywood?” At that moment, he spots the finance guys in a car headed his way. The repo men turn their car around at the light to pursue Gillis. Gillis tries to speed away, but the men are in hot pursuit. Until his car has a tire blowout and ducks into a driveway, hidden. The finance men drive past. “I had landed myself in the driveway of some big mansion that was run down, deserted.” Gillis notices a big garage at the end of the driveway. “If ever there was a place to stash away a limping car with a hot license plate number.” Gillis eyes another enormous foreign-built automobile … It had a 1932 license. "I figured that’s when the owners had moved out.” Walking around the grounds, Joe surmises this was the kind of house crazy stars built in the 1920s, “It was a great big white elephant of a place. A neglected house gives an unhappy look. This one had it in spades. It was like that old woman in Great Expectations, that Mrs. Havisham and her rotting wedding dress and her torn veil, taking it out on the world because she had been given the go-by.”

Suddenly, an old lady’s voice rings out from behind the curtain, a lady wearing sunglasses, “Why have you kept me waiting so long?” Her butler comes out on the porch, inviting Joe inside. He tells Joe to wipe his feet. Max (Erich von Stroheim) tells Gillis he’s not properly dressed for the occasion. Max then tells him to go up the staircase, that Madame is waiting. Then, oddly, Max says if Joe needs any help with the coffin, call him. The woman appears, Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson), saying, “I put him on a massage table in front of the fire. He always wants fire … I made up my mind that we’ll bury him in the garden. Any city laws against that? I want the coffin to be white, and I want it especially lined with satin. Or deep pink. Maybe red, flaming red, let’s make it gay!” As Norma says this, she lifts the blanket covering the corpse, exposing a dead chimpanzee. Joe Gillis is wearing a totally confused look throughout all this, and she asks him how much it will be. “I warn you, don’t give me a fancy price just because I am rich.”

Gillis says she’s got the wrong man, that he only stopped because he had some trouble with his car, a flat tire. “I pulled into your garage until I could get a spare,” Joe awkwardly shares. He says he thought this was an empty house, to which Norma, in outrage, answers, “It’s not … get out!” Then Joe asks, “Haven’t I seen you before? I know your face.” Desmond threatens to call her servant if he does not get out. “You’re Norma Desmond, you used to be in silent pictures, you used to be big,” Gillis remembers. Desmond dramatically states, “I am big. It’s the pictures that got small. There, there, there was a time in this business when they had the eyes of the whole wide world, but that wasn’t good enough for them; they had to have ears to the world too. So they opened their big mouths and out came talk, talk, talk!” Gillis responds, “That’s where the popcorn business comes in. Buy yourself a bag and plug up your ears.” Desmond over-dramatically continues, “Look at them in the front offices, all masterminds, they took the idols and smashed them, the Fairbanks, the Gilberts, and the Valentinos. And what do we have now, some nobody.”

Gillis calmly states he’s not an executive, just a writer, and Norma seems quite interested. “You are writing words, more words. You wrote the words and strangled this business. There’s a microphone right there to catch the last gurgle. And Technicolor!” Joe puts his finger to his mouth and shushes her. He sarcastically says, “You’ll wake up the monkey.” Norma again demands he get out, this time calling Max. He exits, saying next time he comes here, he’ll bring his autograph book or a cement slab for her footprints. As Joe is descending the large staircase, Norma yells down about Joe really being a writer. She asks if he has written pictures. She then invites Gillis back to talk. They walk to a room, a shrine of Norma Desmond’s accomplishments.

Norma asks, “Young man, tell me something, how long is a movie script these days, how many pages? … This is to be a very important picture. About me, I’ll have DeMille direct it. We made a lot of pictures together.” Gillis says sarcastically, “And you’ll play Salome, to which Norma answers matter-of-factly, “Who else?” Gillis, who doubts her veracity, tells her he didn’t know she was making a comeback. Desmond’s face erupts in rage, and she says, “I hate that word, a return to the millions of people who have never forgiven me for deserting the screen.” She gives a script for Joe to read and tells him to sit down. Soon, the actual undertaker with the baby coffin arrives. “He must have been a very important chimp, the great-grandson of King Kong, maybe. Gilis is still reading the script at 11, “Silly hodge-podge of melodramatic plots. However, by then I started concocting a little plot of my own.” Norma, who is still sitting directly next to him, asks, well? Gillis finds the script fascinating, and Demond utters, “Of course it is.” Gillis says, “Maybe it’s a little long and maybe there’s some repetition, but you’re not a professional writer.” Norma says, “I wrote it with my heart,” and Gillis says that made it so great. “What it needs is a little more dialogue … it could use a blue pencil,” Gillis adds, but Norma demands, “I will not have it butchered!” Joe nonchalantly adds,” Just an editing job, you can find somebody.” Norma asks who, and that she has to find somebody she can trust. She asks for his birth sign, and when he utters December 21, she explains he’s a Sagittarius, someone she can trust. “I want you to do this work,” Norma demands. He claims he’s busy, working on a script, and says he gets $500 per week. Norma says she will make it worth his while. Norma says there’s a room over the garage. Why not stay here? Max will take you there.

“I felt kind of pleased with the way I handled the situation. I dropped the hook, and she snapped at it. Now my car would be safe down below while I did a patch-up job on the script. And there should be plenty of money in it. Talking to Max, he says Norma Desmond is quite a character. “She was the greatest of them all. You wouldn’t know her, you’re too young. In one week, she received 17,000 fan letters. Men bribed her to get a lock of her hair.” And Max continues an array of such stories. As Max slowly leaves, Gillis thinks of him as slightly cuckoo, too. “A stroke, maybe. Come to think of it, the whole place seems to have been stricken with a kind of creeping paralysis, out of beat with the rest of the world, crumbling apart in slow motion.” Looking outside, Joe sees a decaying tennis court and an empty, rotting swimming pool. Finally, he sees the last rites for the chimp with the white coffin, Max, and Desmond laying the coffin in a pre-dug hole. “Performed with the utmost seriousness as though she were lying to rest an only child. Was her life really as empty as that? It was all very queer. But queerer things were yet to come.”

That night, Joe had a strange dream about an organ grinder. The organ was all draped in black, and the chimp was dancing for pennies. When he opened his eyes, the music was still there. During the night, somebody brought in all of Joe’s belongings, his books, his typewriter, and his clothes. “What was going on?” Joe rushes into the main quarters of the mansion and finds Max playing organ. Max claims he brought all of Joe’s things to his room himself. Norma, sitting on a couch behind them, says she ordered Max to fetch his things. She felt it was a great idea if they worked together. “There’s nothing in the deal about me staying here,” Joe angrily states. Norma says she has already paid three months' rent on Joe’s apartment. He wanted to get out of the mansion in two weeks’ time, “But it wasn’t so simple getting some coherence in those wild hallucinations of hers. And what made it even tougher was she was around all the time, hovering over me, afraid I’d do injury to that precious brainchild of hers.”

Joe throws several typewritten pages in the trash, and Norma asks what those pages are. Gillis responds, “Just a scene I threw out … the one where you go to the slave market, it’s better to cut directly to John the Baptist …” Norma, in distress, says, “Cut away from me?” Gillis responds, “Honestly, it’s a little too much of you. They don’t want you in every scene.” Ranting, Norma says, “They don’t. But why do they write me fan letters every day? Why do they beg me for my photographs? Because they want to see me, Norma Desmond. Put it back!” And Norma returns to a table signing autographs.

“I didn’t argue with her. You don’t yell at a sleepwalker. He may fall and break his neck. That’s it, she was still sleepwalking among the giddy heights of a lost career, playing crazy when it came to that one subject: her celluloid self. The great Norma Desmond. How could she breathe in that house so crowded with Norma Desmonds?” The camera pans around the room stuffed with photos of Norma and other artifacts.

Two or three times a week, Max would pull on a rope pulley in the living room to reveal a giant white screen behind a painting, to show movies. She claimed that it was so much nicer to see a movie inside the mansion, “The plain fact was she was afraid of the world outside, afraid it would remind her that time had passed … They were silent movies and Max would run the projection machine, which was just as well, It kept him from giving accompaniment on that wheezing organ. She’d sit very close to me, and she would smell of Two Roses, which is not my favorite perfume by a long shot. Sometimes while we watched, she would clutch my arm or my hand, forgetting she is my employer. Just becoming a fan, excited about that actress on the screen. I guess I don’t have to tell you who the star was. They were always her pictures. That’s all she wanted to see.” Norma looks intently at the screen and says, “Still wonderful, isn’t it? And no dialogue. We didn’t need dialogue; we had faces. They don’t design pictures like that anymore. Those idiot producers. Haven’t they got any eyes? Have they forgotten what a star looks like? I’ll show them, I’ll be up there again, so help me.” Desmond’s dialogue develops from intensely low-volume to a standing rage, physically posing, arm outstretched, highlighted by the projector’s light.

While playing poker with an assembled group of silent film actors, including Buster Keaton, the repo men from the finance company arrive and desire to speak to Joe Gillis. Norma, having great fun playing cards, does not wish to be disturbed by Joe’s request to borrow money to pay the men off. They already have a tow truck and are taking Joe’s car from the garage. Norma comes out just as the tow truck is ready to pull out, and she says not to worry, we already have a car, handmade for $28,000. She entertains herself by having Max, her, and him drive around in the Hollywood hills. She grows tired of his low-rent clothes and buys him new outfits.

In late December, the rains came, “Great big package of rain, over-sized like everything else in California. It came right through my old roof of the room above the garage. She had Max move me to the main house. I didn’t much like the idea. The only time I could have to myself was in that room. But it was better than sleeping in a raincoat and galoshes.” Max says the room was formerly used by her husband, as Norma was married three times. Joe asks about the absence of locks on the doors, and Max states that her doctor recommended it. “Madame has moments of melancholy; there have been some attempts at suicide. We have to be very careful, no sleeping pills, no razor blades. We shut off the gas in Madame’s bedroom.” Joe learns from Max that he has written all her recent fan mail.

As Max leaves the room, Gillis takes another glance at the room filled with Norma Desmond memorabilia. “There it was again, that room of hers, all satin and ruffles, and that bed like a gilded rowboat, the perfect setting for a silent movie queen. Poor devil, still waiting proudly for a parade that long passed her by. It was at her New Year’s party that I found out how she felt about me. Maybe I’ve been an idiot not to have sensed it was coming. That was a sad and embarrassing revelation.” The band is playing and Norma is dancing around, sees Joe, admires his tailored new tux, and orders a drink for both of them. Norma then invites him to dance. Noting the passing time, Joe asks about the other guests, and Norma tells him there are no other guests. “This is for you and me,” Norma shares seductively.

“An hour dragged by. I felt caught like the cigarette contraction on her finger.” Norma gushes, “What a wonderful next year it’s going to be, what fun we’ll have. I’ll fill the pool for you. I’ll open the house in Malibu, and you’ll have the whole ocean. I’ll buy you a boat.”

Then the increasingly distressed Gillis interrupts, “You’re not to buy me anything more … Norma, you bought me enough … abruptly standing, Joe yells, “What right do you have to take me for granted? Has it ever occurred to you that I might have a life of my own, that there might be some girl that I’m crazy about? What I’m trying to say is that I’m all wrong for you! You want a Valentino, someone with polo ponies, a big shot!”

“What you’re trying to say is you don’t want me to love you! Say it! And then she slaps him with her right hand.” The look of outrage is written on her penetrating face. Norma walks away suddenly from Joe, going upstairs. Joe simply looks around, the band playing onward. Max silently polishes glasses. Joe also leaves the party, getting his coat and exiting the front door, walking out into the rain, not knowing just where he’s going. “I just had to get out of there. I had to be with people my own age. I had to hear somebody laugh again. I thought of Artie Green. There’s probably a New Year’s shindig going on in his apartment … writers without a job, composers without a publisher, actresses so young they still believe the guys in the casting office.”

Gillis enters Green’s apartment, crowded with party-goers celebrating the New Year, even if it’s not to get any better. Artie Green (Jack Webb) warmly welcomes him, saying Gillis was so distant that Artie almost reported him to the Bureau of Missing Persons. Artie enthusiastically introduces him to the crowd as the well-known screenwriter. Joe asks if Artie can put him up for a couple of weeks, and Artie immediately offers him the couch. Then, out of the blue, Betty Schaefer appears, most festive. Joe asks Artie about using the phone, but a drunk blonde is using it. Betty fetches Joe’s drink, which he forgot. Betty felt guilty for the Sheldrake incident and got out some of his old stories. Betty read a story of his called Black Windows, which she also admits she does not like, except for about six pages. She asks to talk somewhere quieter. Artie interrupts, kidding about Joe stealing his girl.

Betty goes on to explain the six pages she likes: “The flashback scene in the courtyard when she tells about being a teacher … it’s true, it’s moving … I got a few ideas.” All Joe is interested in is living it up and partying. The duo playfully flirt harmlessly with each other.

Finally, the phone is free, and Joe telephones Max to ask for a favor, but in solemn tones, Max replies that he cannot talk now. Joe asks for his old clothes to be put into his suitcase, and he needs his typewriter. But Max tells him, “I have no time to do anything now. The doctor is here! … Madame got your razor from your room, and she cut her wrists,” abruptly hanging up. Betty returns to bring Joe a drink, but he’s out of sorts after the phone call and ignores her, breaking away from the party.

Returning to the mansion by taxi, Joe arrives at the front door just as Max is escorting the doctor out. Asking Max how she is, he directs him upstairs but warns him not to tell the orchestra anything. He enters the bedroom and notices two wrapped bandages on her wrists, then erupts, “What kind of a silly thing was that to do?” Norma weakly replies that falling in love with him was idiotic. Joe continues, “Sure would have made attractive headlines—great star kills herself for unknown writer.” And Norma answers, “Great stars have great pride. Go away! Go to that girl …” Joe tells her he was making up a story about having another girl, citing that the relationship with Norma was a mistake. Joe claims he didn’t want to hurt her. ”You’ve been good to me. You’re the only person in this stinking town that has been good to me. Joe will go, but not until Norma begins to act as a sensible human being. But Norma yells that she will do it again, breaking into audible sobs. As Norma cries, the orchestra breaks into a rendition of Auld Lang Syne. Joe walks closer to the bed, pulls her arms from her sobbing face, and says, “Happy New Year, Norma.” She pauses and finally utters, “Happy New Year, darling,” and she clutches his coat as he hugs her.

Betty telephones Max at the mansion, saying that she must speak to Mr. Gillis. Max states he is not here, that nobody here can give him any information, and asks her not to call again, and he hangs up. Norma asks Max who called, and he says it was nothing, somebody inquiring about a stray dog, Madame. Norma tells Max to deliver the script to Mr. DeMille in person. Gillis emerges from the now fully functional swimming pool. “You really going to send that script to DeMille?” Norma is giddy, having consulted with her astrologist, and now is the best time. She said she never looked better because she never felt happier. “A few evenings later, we were going to the home of one of the waxworks. He was rich. She taught me how to play bridge by then, just as she taught me some fancy tango steps and what wine to drink with what fish.” Stopping at Schwab’s Pharmacy to buy Norma cigarettes, he runs into Artie and Betty, where Betty tells him just how difficult it was to find him. She says Joe Sleldrake is all hopped up about Dark Windows, about the flashback with the teacher. He says it can be made into something.” But Betty needs a fully fleshed-out story; it needs work. ”I’m sorry, Miss Schaefer, but I’ve given up writing on spec. As a matter of fact, I’ve given up on writing altogether.” At this point, Max fetches Gillis to the car.

And this is only the first hour, as there are 50 minutes remaining. This is a good sample of the spicy dialogue it features; it continues into the second half.

Sequences show Cecil B. DeMille realizing Norma’s fans are cruel, and DeMille desperately tries to gently tell her that the industry has left her behind. Scenes include Betty Schaefer and Joe working to flesh out a six-minute flashback, Betty reminding him of when he was young and ambitious. There are sequences of characters writing secretly at night, and Norma living in her fantasy world by day, Joe feeding her delusions and receiving profitable kickbacks. Shots depict Norma preparing herself with an intense health and beauty routine to look ready for her comeback, which will never happen. Max, who discovered Norma at age 16, directed her early films and was her first husband, admits these facts. Artie wants Betty to fly to Arizona to get married. Betty tells Joe she loves him and is no longer in love with Artie. Norma finds the unfinished script written by Joe and Betty and realizes they are in love. Norma calls Betty to ask if she knows where Joe lives and with whom. Joe listens in. Norma confesses she bought herself a revolver. Connie and Betty go to Norma’s mansion. Joe explains to Betty why he lives there, allowing Norma to indulge her wildest earthly needs. Betty leaves Joe without a word. Joe packs his bag, saying he’s leaving Norma. He tells Norma the truth—that Max writes the fan letters and there won't be a movie with DeMille. Joe steps outside with a suitcase, and Norma shoots him three times in the back. Joe falls face down into the lighted pool. Norma, delusional after the murder, hears the news cameras are ready and thinks a Hollywood movie is being filmed. She floats down the stairs, poses for the cameras, and thanks her fans one last time. And yes, Norma is ready for her close-up.

In 1950, Sunset Boulevard depicts the dark reality of Hollywood. Initially, it is hard to determine who is the greater villain: the delusional, likely insane silent film star who tries to keep writer Joe Gillis prisoner, or Joe Gillis himself, who fuels her delusions and manipulates her, gaining the benefits that come with being a “kept” man. Essentially, he is a scoundrel who sacrifices his dignity for money. At least Norma was delusional when committing her transgressions.

A thread running throughout the screenplay is the powerful, seductive force of Hollywood’s promise, herding ambiguous, talented people into the mix, sucking all the creativity from them, and leaving them to slowly wither away, unable to make a living anymore, their own delusions cruelly dashed. Joe is reminded that 22-year-old Betty is as wildly enthusiastic as he once was, and now he sees that world as a sham. Norma fails to see or accept that the movie industry has passed her by, that Hollywood’s once-greatest star is simply a forgotten memory, only as good as her last movie.

And Norma Desmond is only 50 years old, showing how soon an expiration date arrives. The myth about a woman’s age and being a star in Hollywood is shown here to be true. Even in today’s Hollywood, how many women’s movie careers dry up after they age a few years? Yes, a few persevere into old age, such as Meryl Streep, Helen Mirren, and Dame Judi Dench, to name a few. But how many women who made movies 10 years ago are still active in Hollywood today, or how many of those have moved from starring roles to supporting ones?

Only Max Von Mayerling fully accepts this Hollywood angle. He discovered Norma at a young age, directed most of her early films, was her first husband, and ultimately gave up his directing career for her. He came back to her as a man-servant, a person constantly at her beck and call. But his main career was protecting her and her fragile delusions, trying to spare her from the cruelties of the world, feeding into her delusions. Even at the end when Norma descends the staircase after the murder, he directs the lighting and cameras to make her think she is acting in a movie directed by Cecil B. DeMille, sparing her from a harsh pubic who views her as an aging film star accused of murder.

And Gloria Swanson’s performance as Norma Desmond is absolutely one of Hollywood’s greatest. She dominates the screen and practically owns it for almost two hours. She is both pathetic and sinister, weird, playing out her life as a silent film performance. She slithers like a snake, all teeth and wild eyes, married to a distorted face and arms that never quit wandering. Unlike Joe Gillis, who lives his life as a phony manipulator and cad, Norma Desmond feels real emotions, though distorted by her delusions, and she is also a manipulator. Two flawed human beings should complement each other, but in this case, they cancel one another out.

Sunset Boulevard is a Hollywood picture telling the dark truth of what lies under the underbelly of the Hollywood Dream. Director and co-writer Billy Wilder has concocted one of the greatest films ever made about Hollywood, a movie narrated by a dead man, featuring a superb performance by Gloria Swanson, who is quite insane. Interestingly, the movie smashes the Hollywood Dream by creating delusions of its own, and Hollywood is depicted as a psychotic fever dream.

What a movie!

NORMA DESMOND DESCENDING THE STAIRCASE, STRIKING A POSE AT EVERY STEP.

WHILE WATCHING A MOVIE, NORMA DESMOND STEPS INTO THE SPOTLIGHT, WHILE JOE GILLIS (WILLIAM HOLDEN) LOOKS ON.

"I'M READY FOR MY CLOSEUP, MR. DEMILLE!" NORMA WORKS HER WAY THROUGH THE NEWS REPORTERS AFTER THE MURDER.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com