Shadow Readings Part Two

Recent horror genre film books are reviewed.

HORROR/SCIENCE FICTION

written by Gary Svehla

8/5/202512 min read

Queer Screams: A History of LGBTQ+ Survival Through the Lens of American Horror Cinema by Abigail Waldron; McFarlandbooks.com; Order 800-253-2187; 237 pages (6 x 9); 34 photos; softcover $39.95

Revisionist cinema is sometimes rightfully criticized for attempting to re-examine over-examined horror films in outrageous new ways, trying to find something fresh in horror cinema to comment upon. However, every so often, this revisionist analysis is thoroughly necessary, creating a new context through which to view several horror films. Queer interpretation of horror films is not new, but it was also a taboo subject and, therefore, under-discussed and shoved back under the carpet. But with homosexuality rapidly emerging from the closet, horror cinema can be re-interpreted in a queer light, and new truths can be learned.

Abigail Waldron, a fan and student of both American history and American horror cinema, identifies as queer, and she watches and interprets horror films uniquely, informed by her personal history and experiences. What she brings to the critical table is both exciting and, more importantly, valid. Making the old hat new and vibrant keeps these films alive and relevant for this and future generations. In her Preface, Waldron begins by quoting Baltimore’s own John Waters, “Without obsession, life is nothing,” and stating, “Queer Screams is about queer representation in American horror films, and how queer folks can and should reclaim the horror genre as their own ... The main objective of Queer Screams is to show how queer people find catharsis in the horror genre, mainly by using ‘gay sensibility,’ as coined by queer film historian and activist Vito Russo, to identify queer characters and storylines in horror cinema.” Then Waldron reveals how the book will be structured: “I follow the queer experience chronologically through history. Based on the specific decade, horror films reflect the fears of that decade. This includes the fear of the Lavender Menace of the Cold War 1950s, the fear of HIV/AIDS as depicted in homoerotic vampire films of the 1980s, and the revenge through representation of the anti-queer Trump era. I examine films through their historical lens and correlate them to the American queer experience.”

Chapter 1: The Queens of Hollywood (1930s-1940s) found their roots in vaudeville theater, where “theater troupes put on performances often incorporating queer subtext into their shows with the likes of gender-bending and cross-dressing musical and comedic acts.” Such an atmosphere “spawned the careers of numerous queer people who would go on to star on the silver screen.” The Bride of Frankenstein, directed by quirky homosexual James Whale and featuring homosexual co-star Ernest Thesiger, was such an example. Even though director Tod Browning was heterosexual, he “was also an alumnus of vaudeville, who, along with folks like Whale, helped to solidify horror’s vaudeville roots.” To make sure the coarseness of vaudeville theater would not seep into Hollywood productions, Will H. Hays and his Production Code demanded that all films “shall not imply that low forms of sex relationships are the accepted or common thing,” suggesting that adultery and pre-marital sex should not be shown in a positive light.

“Additionally, all references to ‘sexual perversion’ were forbidden ... There is no doubt that sexual perversion included homosexuality. Gay sensibility allowed queer folks to see themselves in a medium such as a film that tried desperately to keep them out. Often, they found themselves in a genre that told stories of outcasts, misfits, and supposed monsters, all of which were representative of either queer feelings, experiences, or societal queer fear that was well understood by queer folks.”

One such movie was Universal’s Frankenstein, the original novel written by Mary Shelley, who was speculated to be queer, as seen in her letter to close friend Edward Trelawny in 1860 after her husband’s death. ‘I was so ready to give myself away—and of being afraid of men, I was ready to get tousy-mousy for women.’ Tousy-mousy sometimes is simultaneously written as ‘tuzzy-muzzy’ and is a slang term for vagina, according to historical lexicographer Jonathan Green.”

“Since its inception, Frankenstein’s Monster has continuously been created and recreated by queer folks.” When well-known homosexual James Whale was assigned to direct the horror classic, ‘Already having earned the epithet, the Queen of Hollywood,’ he deserved not for effeminacy or stereotypical mannerisms but for Whale’s challenge to the system and his eccentric yet nonetheless dignified persona.”

“His vision of a melancholy, misunderstood Monster came from his lover, producer David Lewis, who commented, ‘I was sorry for the goddamn monster.’ And so, Frankenstein became not a tale of a demon, as Dracula had been, but rather the story of a frightened, misunderstood, ostracized, different child.’ The queer Other of Hollywood horror was born.”

Dracula’s Daughter (1936) deals with a forsaken vampire who hopes to lose her obsession with vampirism with the help of Dr. Jeffrey Garth (Otto Kruger) and his friend Dr. Von Helsing (Edward Van Sloan). Zaleska (Gloria Holden) confides to Dr. Garth that “someone ... something [Dracula, her queerness] ... reaches out from beyond the grave and fills me with horrible impulses, to which Garth tells her that her mind has the power to stop these forces. ‘Next time you feel this influence, don’t avoid it. Meet it. Fight it.’ Garth demands Zaleska use her willpower to cure herself of her cursed illness.” But Zaleska must still survive as a vampire and consume blood until she has the ‘will’ to be ‘cured.’”

Zaleska’s manservant, Sandor (Irving Pickle), entices a young woman named Lili (Nan Gray) to pose for a painting for Zaleska for money. As Lili prepares herself, Zaleska asks her to remove her blouse, looking on longingly. It must be noted here that to bite someone’s neck, as with a vampire, there is no need to remove the entire blouse. ‘Why are you looking at me that way?’” Lili questions. In other words, the vampire’s obsession with lesbian sex is more potent than her blood lust. Zaleska approaches the vulnerable Lili as Lily screams from fear, and the scene fades to black. After approving the script, the Breen Office, part of the Production Code of America, “advised that the seduction scene between Zaleska and Lili would ‘need some very careful handling to avoid any questionable flavor ... The whole sequence will be treated in such a way as to avoid any suggestion of perverse sexual desire on the part of [Zaleska] or of an attempted sexual attack by her upon Lily.”

Yes, the sexual undertones of both Frankenstein/Bride of Frankenstein and Dracula’s Daughter have been suggested and written about, but not so much the horror films released in the 1940s and beyond, right through 2021. This is virgin territory to tap. And more than 80 years of horror film history are reinterpreted under the queer spotlight, making for both controversial reading and some thought-provoking history. Besides the chapters on movie decades and discussions of social norms during that decade, Waldron includes Chapter Notes, a Bibliography, and an Index. For people with an open mind, whether you agree with her or not, Waldron explores a new avenue of film study that deserves to be read. And she does so brilliantly!

The Horror Comic Never Dies: A Grisly History by Michael Walton; McFarlandbooks.com; Order 800-253-2187; 178 pages (6 x 9); not illustrated; softcover $29.95

In his Preface, author Michael Walton tells us, “Titles like Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror were the grandfathers of the genre, but just like the mainstream comic industry has changed and evolved from the 1950s until today, the horror comic genre has had its own set of twists and turns. Driven almost to the brink of extinction, villainized, demonized, and practically staked in the heart, the horror comic genre managed to cling to life in the shadows and eventually clawed its way back to the surface.” This book tells the involved story.

Walton divides his book into the following chapters: The History of the Comic Book, The Birth of the Horror Comic Genre, Seduction of the Innocent, The Comics Code Authority, Horror Comics in the Silver Age [1956-1970], Horror Comics in the Bronze Age [1970-1985], The Modern Resurgence of the Horror Comic, and Crossover Hits. The author also includes an Afterword: Whatever Happened to ...?, Chapter Notes, a Bibliography, and an Index.

Looking for education? Let's examine Chapter 2, 'The Birth of the Horror Comic Genre.' “Horror comics can trace their origins back to pulp magazines or ‘the pulps,’ which were fiction and published as quickly and as cheaply as possible ... 128 pages in length and mostly 7 x 10 inches in size. The fiction contained within was ‘sensational,’ ‘lurid,’ and ‘exploitative,’ which led to the term ‘pulp fiction’ to mean any low-brow, low-quality literature.” After the science fiction, adventure, detective/mystery, fantasy, crime, humor, romance, and spicy pulps emerged, introducing such characters as Doc Savage, Hopalong Cassidy, Nick Carter, the Shadow, Buck Rogers Conan the Barbarian, John Carter of Mars, Tarzan, and Zorro, it was easy to notice that horror pulps did not exist at the time. Known as “shudder pulps,” they originated from the detective pulp genre. In the early 1930s, detective pulps published stories with eerie, weird, or supernatural elements. As the stories grew in popularity, pulp magazines were launched to print the new ‘weird menace’ stories ... The stories published in many of the shudder pulps eventually became so lurid and graphic that people began speaking out against the increasingly disturbing content, and the shudder pulp genre began to lose popularity (and circulation numbers) in the early 1940s.”

However, this was not the end of the horror comic, as it continued to emerge in regular comics published during World War II. “Batman even had a run-in with the supernatural about this time. In Detective Comics #31, Batman meets a hooded villain, the Monk. As it turns out, the Monk was Niccolai Tepes—a vampire. Tepes is never revealed to be related to Vlad Tepes—Dracula himself—but the reader can only assume some relationship.”

But if we are to confront a vampire, what about the Frankenstein Monster? “Early comics would draw from classic literature for horror elements as well. Prize Comics #7 ran the eight-page feature, ‘New Adventure of Frankenstein’ ... [taking] Mary Shelley’s famous creature and setting him loose in 1930s New York City.” As Walton notes, the Monster is called Frankenstein. “In 1945, the title was converted to a humor series with the publication of Frankenstein Comics #1. The humorous take on Frankenstein ran through Prize Comics #68 (March 1948) and through Frankenstein Comics #17 (February 1949). The creature was now known as “The Merry Monster,” who ‘buys a house in the suburbs and sits about adjusting to peacetime life, complete with homeownership woes and backyard barbecues.’ The title was revived, similar to The Monster, and returned to its horror roots in 1952.

In June of 1943, Classic Comics adapted literary classics to comic book form, starting with “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” followed in the next issue with “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” According to Walton, these were the first horror comics to feature horror as a “full-length” story.

Before the James Warren comic magazine emerged, “Eerie Comics #1 was a 52-page, full-color comic book published in 1946. The cover featured a sinister-looking fiend (bearing no small resemblance to Count Orlok from the movie Nosferatu) wielding a wicked-looking knife while a young woman lies helplessly bound in front of him ... The full moon behind them silhouettes the entire scene... The book is an anthology of six different stories of the supernatural and macabre.” It sounds very similar to the EC horror line of publications, which resulted in several more years. Walton says it is considered the very first horror comic.

This book discusses actual horror comics, both before and after EC Comics, including one-offs and short-lived titles. Some cover illustrations or interior panels would have been excellent, but no illustrations are included here. Sometimes, I felt as though I was reading a history of the comic industry, with a focus on horror. The book is well-researched and reveals many things I did not know, but I felt the focus wasn’t narrow enough in some sections. The book does come recommended for what it does well.

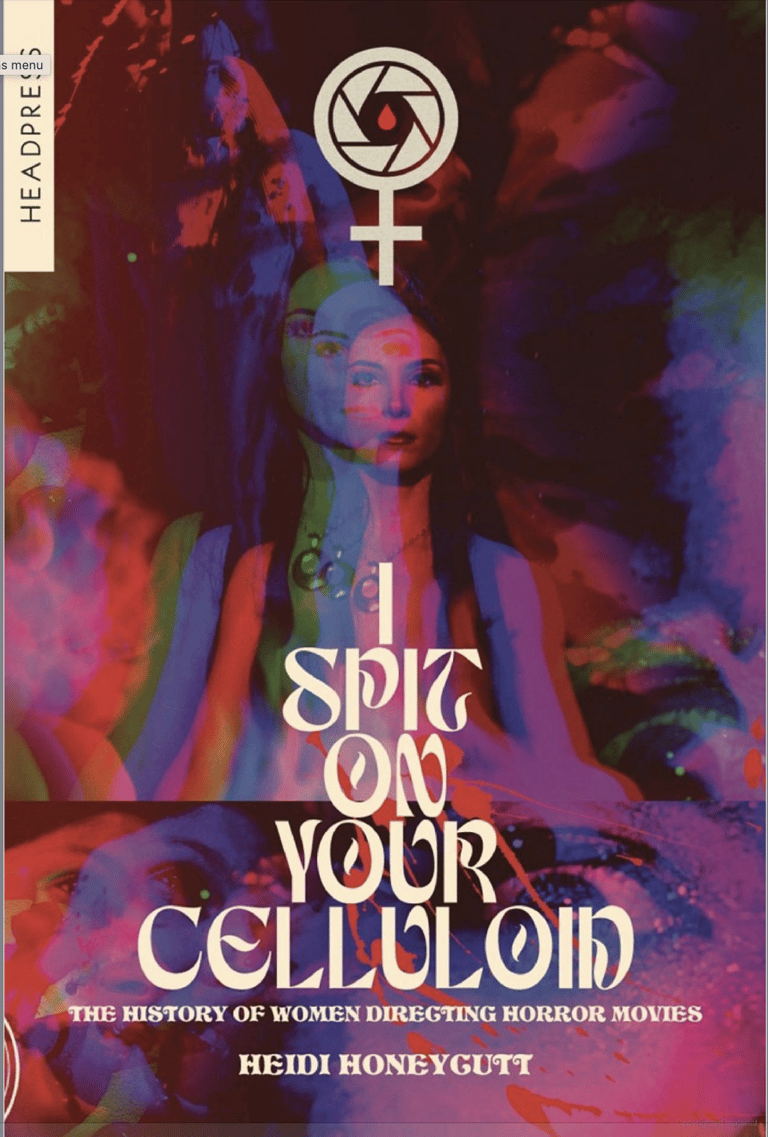

I Spit On Your Celluloid: The History of Women Directing Horror Movies by Heidi Honeycutt; a Headpress Book headpress.com; 456 pages (6 x 9 inches); 100 plus illustrations, over half in color; softcover $32.95

In the Foreword, author Heidi Honeycutt is described as “a beautiful young woman with red hair who wishes to know the meaning of life. She decides to seek enlightenment from horror films,” and we embark on an exploration of the early and primarily current worlds of horror cinema. However, it is mainly men who have directed these horror films. “But she finds herself strangely drawn to the (mostly lower budget) films made by women, and she makes it her lifelong quest to understand what these women are trying to say.” Honeycutt attributes the lack of women directors to organized religion. “Religious mythology is often an inspiration for supernatural themes. The Bible, Catholic dogma, or Christian superstitions with dark themes are used to create a force or a character that threatens other sympathetic characters ... Christianity, which started as a belief system on love and self-sacrifice, vilified the goddess from the very beginning or at least from the moment that the resurrected Christ ascended to heaven and left his female followers at the mercy of a male-dominated society. Much evidence shows that Jesus respected female disciples, whose gospels were later destroyed by the early Church Fathers. And when women continued to demand a voice in spiritual matters of the church, bishops, priests ... emperors, and kings tightened the reins ... Women who wanted agency over their bodies and spiritual lives became blasphemers and heretics, punished with torture and death ... Satan seems to be the only Supreme Being who can speak directly to women ... the villain is often the most interesting character in the story.”

In her preface, Honeycutt describes the slow evolution of her book and her writing credentials. “When an average horror convention attendee was asked to name five horror films directed by women, they could get about three (Pet Sematary, Near Dark, and American Psycho). Sometimes, they’d get to five and mention Ravenous and Stripped to Kill. After that? Fans, men and women, couldn’t name any more. But I knew there were many, and now I know there were thousands.”

In her introduction, she provides more detail about the book's logistics and her qualifications. Her first approach is the misunderstanding that female directors are boring. “Overly academic, well-meaning authors have made the history of women directors boring to mainstream film fans. Film fans don’t want to learn about social and Freudian feminism in Stripped to Kill (1986). Authors writing from this point of view are writing for themselves and other academics rather than for audiences who watch movies ...” Honeycutt seems to be admitting that her kind of female-directed film cannot hold up to intense critical analysis, so one needs to leave their barometer of how we judge these films at home. We should use a different skill set to analyze this type of movie. Honeycutt then admits that "now is the time to investigate female movie directors, and that in the last 20 years, much more relevant information has become available. It is essential to mention that the book does not cover traditional horror films of the past. In the book's early chapters, I cover films that are not conventional horror films. These early films had horror elements and laid the groundwork for future films in the horror genre.” She notes that many women's directions and specific horror films turned out to be dark, but non-horror, upon closer examination. Finally, Honeycutt asks whether men and women make the same types of horror films. “What’s too much T&A? How do you argue that? You and I are men, and we look at women differently. A woman director has a different point of view toward sexuality.” After discussing the question, the author answers, “But are they different? Yes. And no.” And she spends the rest of the book showing why.

The book’s second chapter, "A Land of Both Shadow and Substance: The United Kingdom and the 1950s and 1960s," discusses decades of particular interest to me. “Women had all but disappeared as directors by the 1920s. Except for a handful of Hollywood films directed by Dorothy Arzner and several independent filmmakers and animators in Europe, women did not direct films once sound technology came to theaters.”

Here’s a criticism: Honeycutt points out that when sound pictures started, female directors disappeared. She must prove that some women directors slowly emerged over the decades. However, her coverage of the 1950s and 1960s spans 36 pages, and she mentions the pivotal director Ida Lupino as a major female director of these decades. Of course, there were others, but Honeycutt proves in 36 pages that women in the 1950s and 1960s did not direct too much horror. We have film noir coverage, as well as television horror through shows like Thriller, The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and a notable contribution from a female director to Dark Shadows. We have some anthology television programs, short films, and stand-alone chillers directed by women in Britain. So, primarily melodramas, mysteries, suspense, and crime thrillers substituted for actual horror, and most of it was on television as part of an anthology TV series. And while a good deal of the chapter is devoted to film noir’s The Hitch-Hiker, directed by Ida Lupino, it is in no way horror. I commend the author for unearthing so much content created by women directors, but not much of it belongs in our genre. Even many episodes of Thriller and other horror-themed programs do not!

However, besides chapters devoted to the films of female directors, the author provides notes and an index for further consideration. The book is well-researched and expands upon its basic thesis in exciting ways, but when it comes to horror, it is the films of the 1970s and beyond that attract attention for female directors and do so quite well; the earlier parts of the book have to stretch the point and suspend disbelief.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com