Shadow Readings Part One

Recent horror genre film books are reviewed.

HORROR/SCIENCE FICTION

written by Gary Svehla

7/29/202516 min read

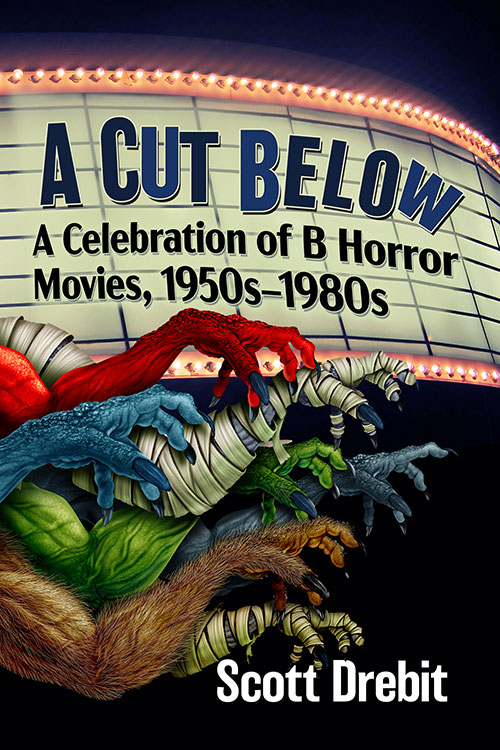

A Cut Below: A Celebration of B Horror Movies, 1950s-1980s by Scott Drebit; McFarlandbooks.com; Order 800-253-2187; 234 pages (6 x 9); 60 photos all in color; softcover $29.95

Where are today’s “B” pictures? How does a writer born in 1970 look at the world of cheap cinema made between 1950 and 1980? These so-called “a cut below” movies are some of the perennial favorites of film buffs everywhere. Author Scott Drebit attempts to categorize such “B” pictures into the following chapters, which he names as different “festivals”: The Animal Kingdom; Those Darn Kids!; The Blood on Satan’s B-Roll; Chop Chop Till You Drop; Any Portmanteau in a Storm; Terror in Technotown; Black Bacon Bloodbath; If You’re Undead and You Know It, Clap Your Hand; What the Film; Duct Tape and Stardust; Potluck of Horror; Around the Weird in a Day; The Past, Present and Future of Horror: Or How to Hit Your Word Count and Close Out the Book; and Index.

In his Preface, Drebit reminds us of what “B” films are, the second or “B” film to round out the double bill, coupled with an “A” feature, but we realize it could easily be a double feature of two “B” features, one a tad better than the other. “I’m drawn to this specific time frame because there’s a lot of cultural symbioses between viewing platform and viewer: radioactive monsters in the 1950s during the Red Scare, the more grounded approach of the 1960s, the societal chaos of the 1970s, and finally into the 1980s when the censors cracked down on our beloved genre.” Drebit praises the “B” movie, saying they were made under “less-than-ideal conditions,” with “fewer funds” and “unproven talent,” which translates into “a great idea, possibly unwieldy, made with passion, heart, and Cthulhu willing, some talent.” “B” films usually allow “a lot more creative control.” Detailing his love of horror growing up amid video stores in the 1980s, Drebit tells us, “We are here to celebrate the horror films you had to beg your parents to rent at the video store.”

To get a “feel” for the book, let us examine a 1950s film and a more recent film. Our list of the 1950s includes The Bad Seed, The Fly, Invaders from Mars, Plan 9 from Outer Space, Fiend Without a Face, and Incredible Shrinking Man. Let us examine The Fly. Drebit tells us that the 1958 original “was eventually eclipsed by its admittedly superior remake,” but we should enjoy “the many-leveled charms” of the original. Charming is the proper word for this movie since “it is a romantic tale about a boy, a girl, a teleportation device, and an insect that comes between them.” The author paints this original as quaint, polite, and well-mannered. “In the light of David Cronenberg’s 1986 classic re-imagining, the original is often viewed as a somewhat quaint relic of its time ... a trifle.” Today’s critics usually portray the 1950s as the perfect decade to raise a child, a laid-back and slow-moving era (even I am guilty of that). Still, in reality, it was a world of segregation, Jim Crow laws, nuclear destruction, poverty, and communism. It was no more quaint unless you wore blinders and ignored the social issues of the time. And yes, women were still second-class citizens. For kiddies growing up then, they thought the world was Lassie and The Honeymooners. “The easiest way to frighten a kid or teen in the 1950s was through the Red Scare, which was tangible, palpable, and all too real.” Not so for someone born in 1950, for the world of politics was a long way off.

The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 probably ignited the Red Scare in children when we realized the world could be destroyed all too soon. Remember 1959, when Castro overthrew the Batista government of Cuba? Americans thought this was a good thing. Children of that era were naïve and sheltered from the world's evils. We matured in the 1960s.

Drabit spends too much of his two-page review detailing the plot, which everyone knows. Still, he mentions the incredible color immersion, the creepy ending, and Al Hedison’s multi-dimensional performance. The author concludes it does not matter which film was best, as both Flys are from “different times, technologies, and temperaments.” But he called Cronenberg’s film superior in the Foreword, so which is it?

For the top-heavy covered 1970s and 1980s, let us select Prince of Darkness, one of John Carpenter’s most underrated films. (And why isn’t one of the most successful “B” films of all time, Halloween, covered here?) At least Drabit recognizes that Prince of Darkness is an “incredible paean to classic British sci-fi horror with his peculiar bent.” Nigel Kneale, to be exact ... British sci-fi horror is too broad a term. The author writes that when he and his sister first saw the film, he was “underwhelmed,” blaming his decision on his youth and a lack of interest in the subject matter, finding the film “slow, meandering, and unfocused.” But upon reflection, he now sees the film as one of Carpenter’s best and a personal favorite. In the battle between Satan and humanity, one would think Satan is the winner in Carpenter’s universe. Drabit feels “The first half offers the heady exposition and suppositions ... and the second offers a base relief.” The critical opinion of this film hinges on whether the film’s explosive second half delivers on the promise of its first half. Drabit calls this a “me” problem, finding the pacing is “carefully calibrated not to pounce, but rather insinuate–until it’s too late and the demons have infiltrated.” The writer says, “But all his films are where cynicism, mistrust, paranoia reach out and envelope all they encounter.” Drabit ends his discussion by recognizing that the credited screenplay writer is “Martin Quatermass,” as a tribute to the already-mentioned Nigel Kneale. “The back-and-forth banter and dialogue” are mentioned a lot, mainly in the first half, “it works because it possesses ideas ... rather intriguing questions about how and where we come from.”

I appreciate author Scott Drebit’s attempts to capture the essence of what makes each film tick in just a few words, insightful ones at that! Like most modern writers, his insight into decades he only read about (the 1950s and 1960s) is more superficial and lightweight. Still, his analysis of more contemporary films is where he shines, making some meaty comments about Prince of Darkness. The reader might learn more in some chapters than others, but this book is recommended for those who accept that some chapters will be more effective.

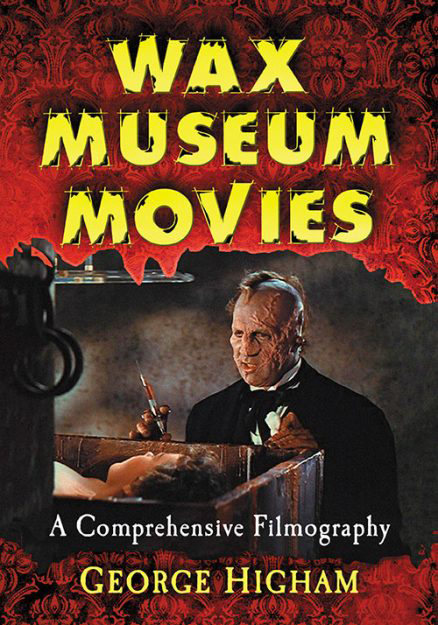

Wax Museum Movies: A Comprehensive Filmography by George Higham; McFarlandbooks.com; Order 800-253-2187; 296 pages (7 x 10); 73 photos; softcover $39.95

George Higham is the ideal candidate to cover wax museum movies, given his passion for wax museums, his background as a sculptor, his experience in special effects, and his degree in film from New York City’s School of Visual Arts. For over the past 25 years, he has also x-rayed corpses at the city morgue. The author begins the book by detailing the mysterious moods of wax museums, which are “where nothing is as it seems. It is a place of wonder, of mystery and horror.” He tells us that 127 films are covered in this book, many of which are “tangential.” But of course, House of Wax lies at the heart of this book.”

For those unaware, “Traditionally, the only parts of wax figures that are wax are the visible parts of exposed skin, head, hands, etc. The bodies were wood, straw, plaster, fiberglass, composite materials, etc.” Hingham goes into a deep dive into the construction of wax figures. Still, we are mainly interested in the movies here. The author discusses the main themes in wax museum movies, such as “The Overnight Dare” or “Waxworks Come to Life.” But he also mentions the origin of wax museum movie tropes or more detailed themes: “as a hideout or base of criminal operations” (Charlie Chan at the Wax Museum), “jewels in the waxworks” (Who’s Afraid?), the corpse-in-the waxworks (The Hidden Menace), and the promise of eternal beauty (Mystery of the Wax Museum). However, these themes often incorporate archetype imagery, such as “the giant vat of wax,” “scarred sculptor,” “black slouch hat/black cloak,” “heads on shelves,” “guillotine,” and “electric chair.”

In Chapter One, which covers movies from 1899 to 1919, he opens his volume by examining a 1899 movie called Royal Waxworks. This documentary is also the first to offer a glimpse into wax museums. Still, the film has been lost to time, and details “remain a mystery.” Chapter Two covers films from 1920 to 1929, which includes the well-known Paul Leni film, Waxworks. Chapter Three gets much more interesting, covering the classic Mystery of the Wax Museum starring horror film icon Lionel Atwill. Higham’s analysis, which spans seven pages and includes photographs, is the perfect way to evaluate the book.

Once lost for decades, the film’s initial 1933 release garnered “lackluster reviews”; once rediscovered in Jack Warner’s “personal archives” and given a significant premiere in 1970, viewers “could not help but feel a tinge of disappointment” when the eagerly anticipated “lost classic” was finally re-screened, warts and all. The better remembered House of Wax “proved its superiority in nearly every way.” Spending some time retelling the scenario, broken up by detailing curious facts (such as this movie was filmed using props from director Curtiz’s earlier Doctor X). Higham also analyses Atwill’s starring performance, citing the subtleties of his starring role as the mad sculptor. Just as importantly, he speaks to the performances of far lesser-known actors. He addresses the idea of “genius” being applied to the wax figures created by Ivan Igor (Atwill), which are merely “quite good,” forcing audiences to “suspend disbelief” to view them as the creation of genius. The author criticizes the “art deco reimagining of the morgue” as “a strange spaceship” that is irrelevant to a second-floor morgue at Bellevue Hospital during the day. Director Michael Curtiz’s style is briefly analyzed when Higham states, “ His Expressionistic stylings blend well with Grot’s art deco sensibilities to create a fantastic New York City that never was.” He explains that Igor’s laboratory was another impossible space, while the museum above “seems overly large and adheres to Grot’s art deco predilections.” Because of the “harsh” two-strip Technicolor photography, the lights constantly damaged the wax figures, so L.E. Oates (who created the wax figures) hired Clay Campbell (who worked with wax figures in movies such as Charlie Chan and the Wax Museum) “to be present during the shoot to attend to the figures” The author cites: “Every cinematic sin presented by Mystery of the Wax Museum was atoned for 20 years later with ... House of Wax.

Indeed, the House of Wax coverage spans over seven pages, containing photos. Higham notes, “Vincent Price made a compelling, charismatic antagonist whose villainous charm contrasted with Lionel Atwill’s bitter Ivan Igor from Mystery.” Fighting the constant battle with emerging television, the Warner Bros. production was rushed into production in Technicolor and 3-D, utilizing the technology of Arch Oboler’s 1952 release, Bwana Devil. Director Andre de Toth, who had only one eye, established the standard for 3-D films to come. “His direction set the bar for 3-D films forever after. His visual approach rarely ‘came at you’ as so many 3-D films are prone to do, instead ‘pulling you into’ an intriguing, multi-dimensional world.” Also, Warner Bros. planned to release the film with full stereo sound to outclass television. “This proprietary audio technology proved to be more expensive for theaters to install than accommodating the polarized 3-D system ...” The author explains the improvement to the story and casting that resulted in a far better film than Mystery. Higham details the premiere of the movie and the disproven suspicions that Vincent Price had Communist leanings in 1952. “Fearing he would never work again, Price took the bull by the horns and arranged for his own FBI interrogation. The grueling experience acquitted the man, and within one week, he had two job offers.”

Catching up to the modern day in movies, the voraciously annotated book concludes with Chapter Notes, a lengthy Bibliography, and an Index. I am impressed with Higham’s extensive research and scholarship. Even though he writes about both lost films and heavily covered films, as well as everything in between, he always finds something new to say, adding depth to over-researched films where we thought the last word had been written. I was both entertained and educated by Wax Museum Movies, and I highly recommend it!

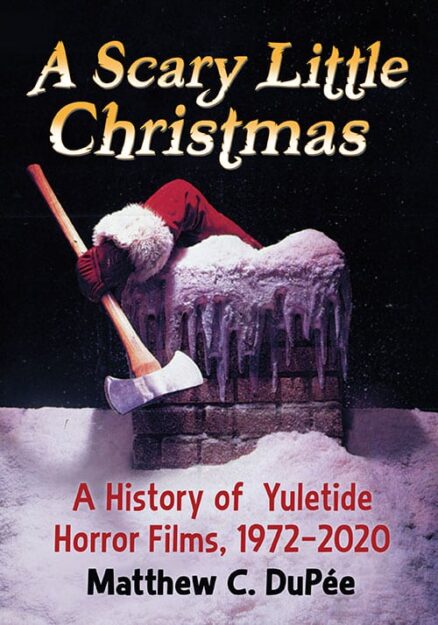

A Scary Little Christmas: A History of Yuletide Horror Films, 1972-2020 by Matthew C. DuPée; McFarlandbooks.com; Order 800-253-2187; 370 pages (7 x 10); 174 photos; softcover $49.95

I once had a friend, Rick Neff, who would entertain my wife, Susan, and me by hosting a large food spread and holiday celebration every Christmas Eve. The evening would often conclude with Neff showing a Christmas-themed horror movie, a relatively rare occurrence in the early 1970s. Today, the fact that a book exists to cover such films almost boggles the mind; who would have ever considered that a subgenre was born and evolved throughout the decades? DuPée’s book includes the following chapters: Claustrophobia: Psycho Santas; Yule Die; Christmas Slashers; Homicidal Holidays; Stocking Stuffers; Killer Christmas Trees; Krampus, the Christmas Devil; Zombie Holidays and Christmas Cadavers; Intergalactic Christmas Mayhem; Evil Christmas Spirits; and Christmas Horror Anthologies. Also included are an Index, Bibliography, Chapter Notes, and an Annotated Christmas Horror Filmology. This book is well-researched and organized.

In his Preface, DuPée tells us the genesis of this book began more than 25 years ago when he first watched Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974). The modest-budgeted film inspired the writer to attend film school at Point Park University in 1998 to begin “a guerrilla filming career and continue the study of horror films.” Though well-read in the genre, he noted the absence of a book on his favorite subgenre, the Christmas Horror Film. When he started writing in earnest, two books about his favorite subgenre, Yuletide Terror: Christmas Horror on Film and Television and Giftwrapped & Gutted: The Trashiest Christmas Ever Made, were published, but the author felt he could do even better. To make his book a cut above, he interviewed directors, writers, producers, special effects artists, music composers, and “everyone in between.” DuPée “tracked down 100 such creators.”

In the Introduction, he admits that even though horror and dark comedy elements were present in Christmas Eve (1913), The Phantom Carriage (1921), and Who Killed Santa Claus? (1941), it wasn’t until Amicus released Tales From the Crypt (1972) “that a darker, more controversial contemporary cinematic depiction of Christmas horror emerged,” showcasing a homicidal killer dressed as Santa Claus ... and we never looked back! Soon, other Christmas-themed movies emerged on the scene: Home for the Holidays (1972), Black Christmas (1974), Christmas Evil (1980), To All a Good Night (1980), and Silent Night, Deadly Night (1984). As the author quotes Mark Connelly, Christmas becomes “an emotional shorthand to impact mood and the mise en scène to the viewer.”

Most refreshingly, DuPée includes his discussion of the films organized around theme-based chapters. For instance, Chapter One follows psychos dressed as Santa Claus. The author’s discussion of Silent Night and Deadly Night is typical of the book’s analytical tone and method, serving as the primary focus of the first chapter. DuPée starts by briefly describing the film's merits and includes background information. “Silent Night, Deadly Night endures as one of the subgenre’s most notorious, significant, and cherished entries. Controversial for its production trials and tribulations and subsequent advertising and marketing difficulty, it is steeped in rich and savory tales of industry treachery, missteps, and creative brilliance.”

Providing background information, DuPée states that in 1981, a 24-year-old agent in training at the William Morris Agency in Beverly Hills, Scott Schneid, received a horror script from an unknown writer, Paul Caimi. Schneid, a Harvard graduate, had maintained his role as an alumni career adviser for students still enrolled at Harvard and interested in the film industry. Caimi recently wrote a 78-page screenplay entitled He Sees You When You’re Sleeping while at a Harvard seminar, and Schneid was not impressed with it. Still chatting with Caimi, he soon realized the screenwriter had known Schneid’s older brother, who had also attended the same prep school in New Jersey, and decided to work with the novice writer. Soon, Schneid conferred with friend Dennis Whitehead, a development executive. While Schneid did not know “B” films, Whitehead did, but Whitehead desired to gut Caimi’s script to pull “out the psycho in the Santa suit killing people around Christmas, that is it. There was no backstory ... no story of a child traumatized by his parents’ death, going to visit his grandpa.” So they developed a whole new story from Caimi’s draft,” And the story of bringing it to completion is further explained. Finally, “armed with a treatment of the project, Schneid and Whitehead raised around $30,000 and paid Michael Hickey, a Writer’s Guild member, a minimum to complete a feature-length script.” Then DuPée spends considerable time detailing the coming together of the film's production, told in part with in-depth interviews with people involved. The details are pervasive. Then, we follow the production of the four sequels that were produced in the wake of the first one, as well as the reboot of the original. If you're looking for production details, this book is for you rather than an in-depth film analysis. But the first chapter does not end here; for the remainder of the chapter, other Santa-based psychos horror movies are introduced, and production details are covered for a slew of far lesser-known films than the Silent Night, Deadly Night series, which concludes the first chapter at 61 pages.

This book might be the final word for gung-ho fans of this Christmas-based subgenre. DuPée’s research and conversations with the prominent artists of productions are as definitive as they come. I would have enjoyed a more insightful critical analysis, but I do not want to delve into the production details of a subgenre that doesn’t quite pique my imagination. However, I admit that I am not the intended audience for this book. Still, I commend DuPée for devouring his subject matter with gusto and doing the difficult work of producing a truly excellent book for the hardcore fan, not the casual viewer.

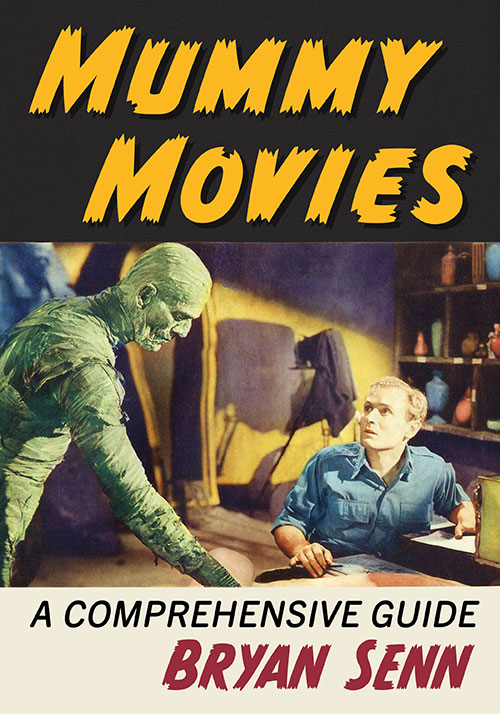

Mummy Movies: A Comprehensive Guide by Bryan Senn; McFarlandbooks.com; Order 800-253-2187; 345 pages (7 x 10); 160 photos; softcover $75.00

After his comprehensive coverage of Zombies, Ski films, Double Features, Werewolves, Golden Horrors, Sixties Shockers, and a few others in individual books, writer/historian Bryan Senn tackles Mummy movies in his latest effort. He is so inclusive that my wife’s minimal budgeted independent Terror in the Pharaoh’s Tomb is granted three pages of coverage.

In his lengthy Introduction: The Mummy Rises, Senn reminds us “that the inspiration for the perambulating ancient corpse known as the Mummy came from the 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb by British archaeologist Howard Carter and his financial backer Lord Carnarvon.” This historic event only came 10 years before Universal’s The Mummy was released. In an on-set interview during the production of The Black Room, star Boris Karloff stated, “My worst make-up was in The Mummy. That took nine hours to get on. There were two make-ups in that—one the Mummy in the tomb, and the second the Mummy come to life.” Senn continues, “While the character of the Mummy, as we know it today, entered the cinematic consciousness with Karloff’s brilliant portrayal in 1932, even that ominous figure had to undergo a significant transformation to become the classic monster we know and love today. The popular notion of the Mummy came into being with Kharis, first played by Tom Tyler in Universal’s The Mummy’s Hand (1940), then by Lon Chaney, Jr. in three further sequels.”

Citing trends in Mummy movies, Senn briefly covers silent film Mummy movies, most of which deal with tomb invasions and resurrections, leading to 1932’s The Mummy and its many sequels, culminating in 1955's Abbott and Costello Meet The Mummy. The 1950s produced occasional Mummy films such as Pharaoh’s Curse (1957) and Curse of the Faceless Man (1958). It then forwarded two different trends on foreign soil: The Aztec Mummy in Mexico, which produced two direct sequels, and Hammer’s reinterpretation of The Mummy in 1959, which spawned three sequels. Senn continues the history lesson of Mummy movies, from those made in the 1960s to the present day.

The author also covers literary sources, including Living Mummies, but notes that The Mummy lacks any pivotal literary sources, such as Bram Stoker’s Dracula or Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which has earned the film series less respect due to its lack of scholarly foundation.

The Introduction: The Mummy Rises is neatly divided into subdivisions, such as "The Mummy as Pop Icon" and "The Mummy’s Appeal," "but is a Mummy just a Mummy?"; Real Mummies vs Reel Mummies, The Sands of Time ..., King Tut Has Much to Answer For, Guanajuato Mummies, A Note on Nomenclature, and About the Book. Besides this Introduction, the main chapter, The Movies, occupies almost 300 pages; Senn also delivers a Chronology, an investigation of Series and Subsets, a Bibliography, and an Index. Coverage of Mummy movies can vary from two pages for lesser entries to 7 pages for major ones. The stills chosen for illustration purposes are not typical and have been carefully selected.

We must examine the 7-page coverage of the Universal classic The Mummy, starring Karloff the Uncanny. The coverage begins with a truncated cast and credit listing before Senn notes that the iconic Mummy image is derived from four sequels, which had little in common with the subtleties of this first masterpiece. Senn states, “Karloff’s Mummy is not a shambling, inarticulate monster; he is an intelligent being of power, a master of the black arts.” Then, the author retells the entire plot in a single, concise paragraph, which is just the right length. “The Mummy takes a subtle approach in weaving its cinematic tapestry of the strange and terrible. Touching on life, love, and death, The Mummy is poetic horror and one of the greatest, most original fantasy films ever.” Senn covers the first major scene, where the Mummy comes to life slowly and horrifyingly, by practically discussing every frame and angle. After analyzing Karloff’s look in the film, he discusses the supporting cast, make-up guru Jack Pierce, and novice director Karl Freund, who “effectively employs the camera as a thematic device,” noting the actual cinematographer on the film was Charles Stumar. But the director and Stumar worked well together.

Contrary to this, leading lady Zita Johann said her director was somewhat sadistic. This was supported by noted film historian Greg Mank, who interviewed Johann where she said Freund “Threatened to have her pose nude from the waist up; how he saw to it she didn’t get a chair with her name on it, as did the other leading players; and how he worked her so sadistically that, late on a Saturday night, as Karloff was playing a scene with her, she collapsed. ‘I was out for an hour—dead.’” Senn goes on to discuss several outstanding, well-photographed sequences.

Senn confesses that David Manners was the only fly in the ointment, playing hero Frank Whemple. “His annoyingly affected delivery and almost puppyish demeanor as he fawns over the heroine turn him more into a caricature than a character.” David Manners was highly regarded by Universal and won romantic leads in both Dracula and The Black Cat, where he turned in “his regular milquetoast routine.” Senn continues to explore the initial magic of The Mummy as Cagliostro, which would have produced a vastly different film had screenwriter John L. Balderston not transformed this nine-page treatment by Nina Wilcox Putnam and Richard Schayer into Imhotep, which was soon renamed The Mummy. The author then examines John L. Balderston’s input to the film and casting ideas. Then parallels are drawn between Dracula and The Mummy, noting both scripts are virtually alike. Senn ends the chapter by discussing Universal’s “shameless” ideas for ballyhoo, which were outrageous, concluding with a summary of the picture’s merits.

In a film so well-covered by writers and film historians, Senn’s chapter reads fresh, is well-researched, and he manages to say something new, difficult to do when writing about this old chestnut, The Mummy (1932). The entire book does more of the same, especially with less-covered films. It comes highly recommended.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com