Outward Bound and Between Two Worlds: Sailing for the Final Judgment Part One

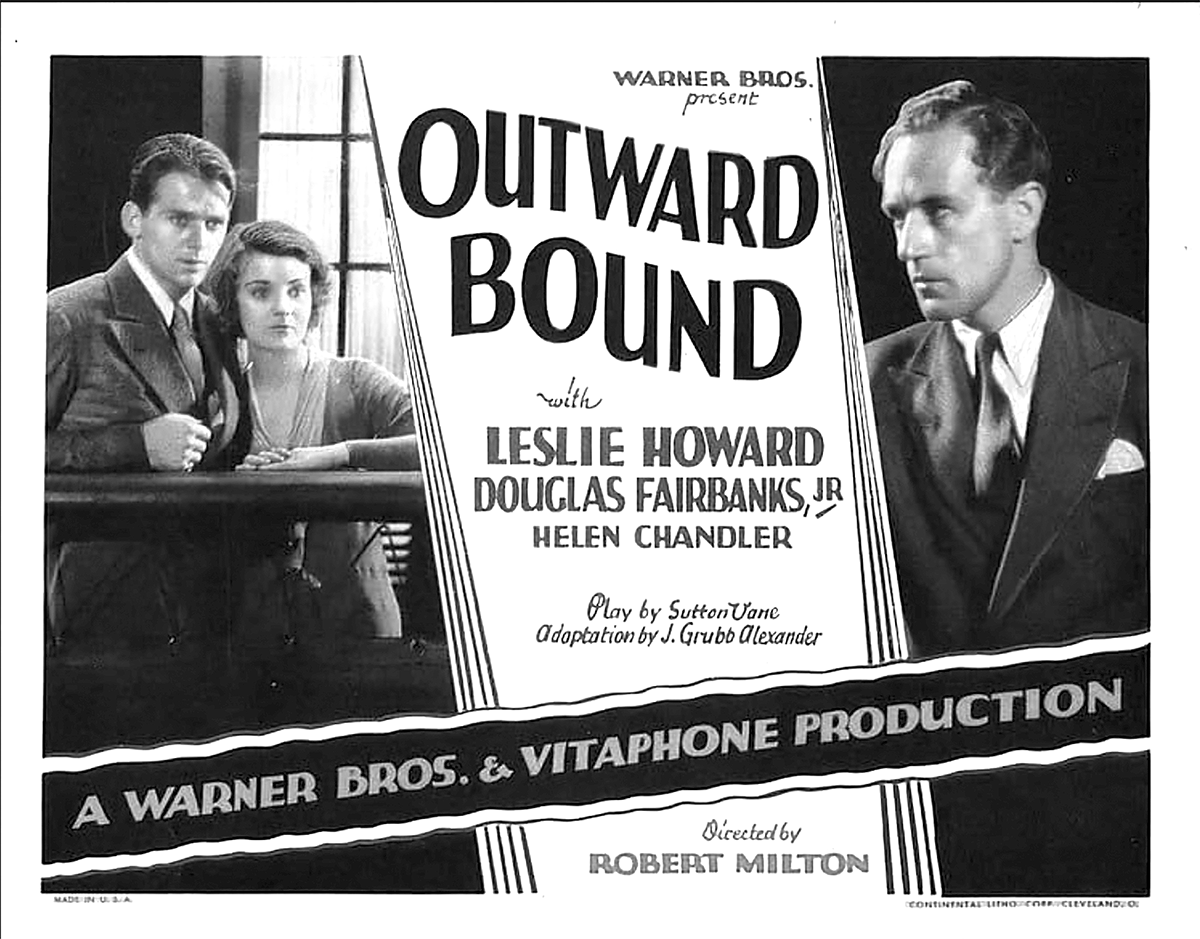

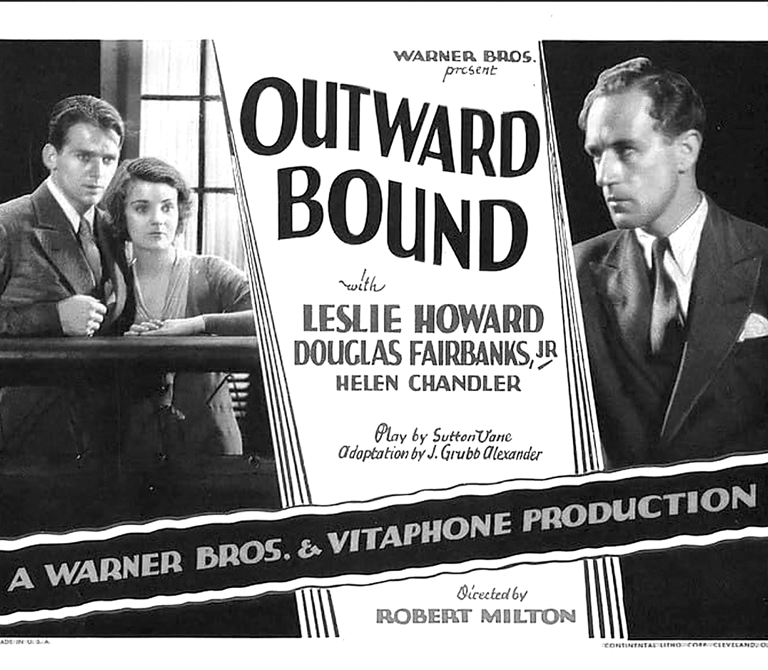

Explore two adaptations of Sutton Vane's play that delve into an imaginary world between heaven and hell, where individuals face judgment at the end of their lives. Discover the themes and interpretations of this thought-provoking narrative. 1 HR 23 MINS Warner Bros.

HORROR/SCIENCE FICTION

written by Nathalie Yafet

5/19/202522 min read

It presented for the first time to the Peoples of the World an entirely new and different conception of Life, Death, and the Hereafter … would the public recognize the profoundly sincere theme of the play and appreciate the strange psychology and glorious sentiment interwoven between the lines … we cordially beg you to place yourselves in the same position as that first night audience in London and see if the deep sincerity of our Vitaphone version of the play impresses you as it has impressed the appreciative theatre audiences of the world.

Portion of the prologue from Outward Bound (Warner Bros. and Vitaphone 1930)

This would be no ordinary night at the movies. The film was based on a play by Sutton Vane, whose acting career was interrupted by his enlisting in the British Army. It was 1914, and he was 26 years old. This, too, was interrupted by malaria, shell shock, and guilt over having left the army. Living through this made a lasting impression. After the war ended, he wrote a few conventional plays.

Then came Outward Bound, which was so unusual in its subject matter as a fantasy drama that no producer would go near it. Instead, Vane produced it himself, renting a theatre in London, painting his backdrops, building his own sets, and bringing together a company of actors, all for a reported total of $600. Outward Bound is about a small, motley group of eight (actually seven) passengers who meet in the lounge of an ocean liner at sea and realize that they have no idea why they are there or where they are bound. Each of them eventually discovers that they are dead and that they're about to face judgment from an Examiner about whether they are to go to Heaven or Hell. In post-World War I England, with its reflective, pacifist mood—many hundreds of thousands of families were still mourning the loss of loved ones, and the nation collectively mourned the decimation of a generation of students, artists, writers, and musicians—the play struck a responsive chord and was an immediate success.

Outward Bound was moved to a larger theatre in London and became the biggest hit of the 1923 season.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

It premiered on September 17, 1923, at the Everyman Hampstead in London, afterward going on to the Garrick, Royalty, Adelphi, Criterion, Comedy, Fortune, and Prince of Wales Theatres to similar acclaim. Coming to the Ritz Theatre in New York City (later the Walter Kerr) on January 7, 1924, it ran for 144 performances. It featured four actors who would also appear in the Warner Brothers Vitaphone version—Leslie Howard, Beryl Mercer, Lyonel Watts, and Dudley Digges. (Leslie Howard took on the male lead, Tom Prior—played by Alfred Lunt on Broadway—which left Howard’s original role of Henry for Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. Ms. Mercer, Mr. Watts, and Mr.Digges played the same parts as they did on Broadway.) Again, it was a smash hit.

Mr. Vane reverses the usual procedure. Instead of introducing an intruder from the Undiscovered Country (whence, as Hamlet inexplicably remarks, no traveler returns), he transports us into the midst of the ghostly throng. He makes the ghosts themselves ignorant of the fact that they are dead. One sees a varied group of quite mundane people disquieted at something vaguely unfamiliar in their ship and voyage, troubled by a growing mystery, and finally convinced that they are crossing a modern Styx on a modern ferry face to face with the solemn terror of the hereafter. (John Corbin, the New York Times, January 13, 1924)

Outward Bound is undoubtedly the best-acted play now running, and future indications are that it is bound for a voyage for an unknown period (The Brooklyn Standard Union, January 8, 1924).

Of particular interest for classic horror movie fans was the 1938 Broadway revival, whose cast included Bramwell Fletcher as Tom Prior, Helen Chandler reprising her role of Ann from the 1930 Warner Bros. movie, and Vincent Price as the Reverend William Duke. It ran for 255 performances and was directed by Otto Preminger.

Outward Bound was not a typical Warner Bros. effort. The studio was known for gritty gangster movies, musicals, and adventure films. They didn’t really know what to do with it. One of the stars, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., didn’t even like it. "I never saw all of it," said Fairbanks about the film. "It gave me the creeps. Still does, just thinking about it. It was a prestige picture, never made a cent." Bawden, James and Miller, Ron Conversations with Classic Film Stars: Interviews from Hollywood’s Golden Era (Lexington, Kentucky University Press of Kentucky March 4, 2016) 97.

Fairbanks, Jr. made only one other supernatural film towards the end of his career, Ghost Story (Universal 1981). The year after Outward Bound, Helen Chandler was the definitive Mina Harker in Dracula (Universal 1931). It remains hard to believe that the actress only had two genre credits. "It was her look and delicate features, plus her rather bird-like voice, that added to the metaphysical nature of the picture. The press said that she had stars where her eyes should be." Terry Sherwood, "Helen Chandler—Little Girl Lost," (Stardust and Shadows, August 18, 2020) Blog post.

It’s our loss that Helen Chandler and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. only made one film together. Both are blonde and fragile; he is 6’1, and she is 5’3. They glow flawlessly in sync with luminous, undeniable chemistry, words, and gestures. The tragic young people are enchanted with each other, and we are with them. We believe in Henry and Ann. Each has heart-stopping moments when they temporarily lose track of each other on board the unearthly liner. After Tom first asks Henry if he knows where he’s going, he starts off down the deck. Helen’s Ann steps out from inside and audibly gasps as she runs to him. Later on, after another grilling from Prior, Douglas’ Henry goes on deck in the dark and doesn’t see Ann at first. With mounting fear, he moves down the deck calling her name and turning around. Finally he sees her, stretching out trembling arms, “Ann, come here.” They share their fears that the others know they’re dead and again worry about being separated.

Screenwriter J. Grubb Alexander did an excellent job translating Sutton Vane’s play for the film. He handily removed all the unnecessarily endless conversations and clarified the characters—especially the Reverend William Duke.

The play begins with Henry and Ann (the young lovers) boarding a strange ship manned by Scrubby, an otherworldly steward. But the film gives us a lengthy prologue, followed by a nebulous onscreen title—Somewhere near London. In a small rowboat in cheery sunlight are a serious-looking Henry and Ann with their dog, Laddie (Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. and Helen Chandler). Hours later, in the murky dark, they discuss in Ann’s doorway their plans for midnight. We don’t know yet that they intend to commit suicide then, but we are chilled by the tone of their conversation.

12 o’clock.

Yes, Henry. I’ll be ready. You’re sure? You want to? It’s the only way, dear.

You’re sure? You’re not afraid. We’ll be together, dear.

For always. No matter what people say. Won’t it be wonderful?

Yes, dear. Good night Till 12.

Yes, Henry. Till 12.

This discussion is punctuated by talk about being unable to take Laddie with them and by an unhelpful Bobby calling the dog a “funny-looking mutt.” After the comic relief walks away [an uncredited Walter Kingsford who later appeared in two impressive genre films, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Universal 1935) and as Sir Francis Stevens in The Invisible Ray (Universal 1936)]. Henry grips the front of Ann’s coat while he tries to assure himself that she wants to follow through with their plan. Before he leaves, he kisses her hands as she holds his. It’s a moving few seconds, which emphasizes their deep bond. We see just their window where Big Ben sets the time at midnight, followed by a matte painting of the ethereal outward-bound ship. The play’s stage directions describe Ann and Henry separately, "She is young, but one sees at once that she is nervous." “He is good-looking, quietly emotional, serious, and sincere. He is rather mystic in manner and behaves like a dazed man who has recently received a severe shock.” Vane, Sutton, Outward Bound (New York, New York, Liverwright Publishing Corp. 1924) 16, 17. Scrubby, the steward (and, as it turns out, the ship's entire crew), welcomes them as Henry seems to be in shock. Ann asks for his hand, and he objects to her, treating him “like a child,” but he does take her hand as Scrubby guides them to their cabin. Henry thanks him awkwardly for “showing” his “wife” the way. (Although not definitively stated and from the all-knowing steward’s reaction, we know they are not married.) Alec B. Francis is constantly reassuring, gentle, and calm as Scrubby. The actor made more than 240 films between 1911 and 1934, with Outward Bound being his sole genre credit, which is a shame because he has exactly the right touch for this very unusual film.

Enter Leslie Howard’s perfectly cast smiling Tom Prior in search of a drink. (The actor’s only other genre credit would be Berkeley Square (Fox Film Corp 1933). Scrubby tells him vaguely that they’ll be sailing in a “quarter of an hour or more or less.” After downing an all-Scotch hair of the dog, Prior leans in to describe the “thick” night that he can’t remember anything about. After yet another pull from his glass, Tom remarks on the “gorgeous morning.” (The play then has a line wisely omitted from the film as it would give too much away, Scrubby remarks, “It is, sir. A pity some people should be alive to spoil it.”)

Next up is Alison Skipworth’s deliciously snobby Mrs. Cliveden-Banks. She makes the most of it in her only genre film. Ms. Skipworth was famously memorable as Emily la Rue opposite W. C. Field's Rollo in the Road Hogs segment of If I Had a Million (Paramount Pictures 1932). She and Prior know each other from before and are making small talk as clergyman Reverend William Duke arrives. (Lyonel Watts was an English stage actor with very few film appearances. Despite this, his conflicted yet thoroughly appealing Anglican clergyman completely wins us over and becomes his fellow passengers’ moral compass.) The play has an excruciatingly long back and forth about clergymen being unlucky on-board ships, which screenwriter Alexander thankfully removes. Ms. Skipworth hints at it, being unfriendly enough, causing Reverend Duke to apologize as he backs away, “I’m awfully sorry. I didn’t think introductions were necessary on-board ship. I beg your pardon.”

Beryl Mercer’s sweet charwoman, Mrs. Midget, quietly arrives, nearly giving Mrs. Cliveden-Banks fits. “Am I to be attacked on all sides?” Neither Mrs. Midget nor Reverend Duke does anything wrong, but since the ship has only “one class” (again needlessly hashed over in the play), the unpleasant woman has to suffer the consequences. (Beryl Mercer was the Broadway premiere’s Mrs. Midget. She was later to do solid work in Berkeley Square (Fox Film Corp 1933) with Leslie Howard and The Hound of the Baskervilles (20th Century Fox 1939) with Basil Rathbone and John Carradine). To help her get her bearings, Prior questions the woman (both in the play and film):

Where am I?

On board, on board this boat. Yes. But what for?

How should I know?

Are your tickets and luggage all right?

I don’t know. I ain’t one to worry about little things.

Contrasted with Mrs. Cliveden-Banks fussing about nearly everything, Mrs. Midget becomes an instant favorite. Scrubby escorts her to her cabin, and it’s a mutual admiration society with “ma’am” and “captain.”

Cut to Duke and Prior buoyantly toasting each other as we suspect they have been for a while, which is marred by Lingley setting foot in the lounge. He seems to have nearly missed the sailing and calls out for a drink, rudely responding to Scrubby’s offer of whiskey and soda with, “No, confound you, ginger ale with some ice.” Even though the steward appears omniscient, we suspect he offered the alcoholic drink so that Lingley’s character would be instantly established. He recognizes Prior—who by now is feeling pretty loose—as someone he had “sacked mechanically” for imbibing on the job. Remembering this, Tom hurls a choice assortment of insults, including, “You’re a pompous old idiot … you’re a blue-nosed baboon.” The tirade prompts a “Dear, dear—dear, dear, dear, dear.” from Reverend Duke. Prior can’t resist retorting, “That remark helps matters a lot, doesn’t it?” Tom’s provocations push Lingley towards a heart attack, which is probably how he died. Duke kindly ministers to the frightened man, and Prior gives him the rest of his drink. Lingley swallows one of his heart pills and seeks fresh air on deck. He wonders where he is going and which businessperson he is scheduled to meet. (Montagu Love, according to his Wikipedia page, “was an English screen, stage and vaudeville actor…one of the more successful villains in silent films.” He makes a splendid Lingley, neatly capturing the officiousness, fear, and humor. In 1929, he joined Lionel Barrymore in The Mysterious Island based on the Jules Verne science fiction novel (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer 1929), and 13 years later, he was with Basil Rathbone and Evelyn Ankers in Sherlock Holmes and The Voice of Terror (Universal 1942). Interestingly, he reconnected with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. in Gunga Din (RKO Radio Pictures 1939) as his character Colonel Weed expressively recites the last verse of the Kipling poem over the fallen hero, Sam Jaffe’s Gunga Din.)

Prior privately asks Duke if he’s noticed anything “queer” about the boat, but the Reverend is non-committal. Still uneasy, Tom spies Henry and asks him if he knows where he’s going. Henry tells him that “certainly” he does, but we know he is not certain. Ann runs to Henry on deck, after which he recounts his encounter with Prior. She tries to soothe him by saying his answers were “right.” They have a sweet few minutes worrying about Laddie and if there’s a Heaven for dogs with “no cats” but “plenty of bones and meat and water.” (Screenwriter J. Grubb Alexander thankfully renamed Jock from the play to the far more appealing Laddie.) They finally arrive at the core of their tete-a-tete—have the others guessed their “secret,” can they be separated, what exactly happened, and have they “sinned.” Always the nurturer, Ann reminds Henry that they’ve been “true to each other,” so how could they have sinned? Not yet recovered from the shock, Henry recalls, “something like gas,” closing his eyes briefly with evident pain.

Unknown to them, Tom Prior returns and overhears the whole “gas” duologue. After the couple leaves, Tom grills the ever-calm Scrubby, who definitively states they’re all “quite dead,” without a trace of irony that the destination is Heaven and Hell, and shockingly, that “they’re the same place,” an unorthodox theology that cannot have escaped notice in 1924.

Although they’re all bound for the final judgment, Scrubby appears to be clearing up after serving the evening meal. They can also all drink alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages and rest in their snug cabins, which is probably all part of easing the outward-bound passengers into gradually discovering the truth. Director Robert Milton (who also did the 1924 Broadway premiere) nicely frames a brief shot, through the small window of the dining saloon door, of the group at the table—including Henry and Ann—finishing dinner. Afterward, Mrs. Cliveden-Banks and Mr. Lingley bully good Mrs. Midget as she comes in from the deck (the “street,” as she calls it) at the Reverend William Duke’s invitation. She starts talking about her boy who grew up with her wealthy brother-in-law after losing all her money, when Tom Prior makes a startling entrance through the center doors, urges them not to waste their breaths, and announces, “We’re done for. Every one of us on this boat …we’re dead people!” Duke’s face tells us he believes him, although he tells Prior to “mind your own business” when asked where he’s going. The others try to keep up their self-deception as Tom recounts how he investigated the whole ship and no one was there except Scrubby, who he saw “Sitting cross-legged high up in the rigging.” (Sailors on old masted wooden ships would climb rigging to calculate the distance before landing. The “cross-legged” pose is one of the play’s many religious references. It also pegs Scrubby as introspective and a bit of a sport.) There are no port or starboard lights, and Tom reminds them that none of them know where they’re going. Desperately, he offers to “go quietly” if one of the men will check out the ship and honestly report their findings. Duke is the only one who is willing. To get Henry to “back” him up, Prior once again brings up “gas,” frightening them both, especially Ann.

The Reverend Duke goes out and sees that everything is as eerie as Tom Prior said. While Duke is gone, the whole group (except for Lingley) hears muffled drums. (These supernatural drums, the ship’s foghorn, breaking glass, Laddie barking, and an emergency siren are the sole sound effects employed throughout the film. There is no background music, just the main title, a brief idyll underscoring Ann, Henry, and Laddie on the river, and the closing, which suits the solemn subject.) Duke doesn’t admit what he saw after he returns and falsely says everything is “all right.” Tom lunges at the clergyman, and Lingley—straining—pulls him away. An anguished Prior declares he’s “only trying to help” and make them “understand.” Mrs. Cliveden-Banks states she’s going to “the (unseen) ladies’ writing room,” with Mrs. Midget following. Ann goes on deck, handily getting all the women out of the room so that Duke can apologize to Prior for his deception, done because he “didn’t want to alarm the ladies.” The clergyman saw the ship “black as pitch … no lights anywhere.” He couldn’t even be sure the vessel was “moving” and fearfully escalated to worrying about the boat “drifting” or “crashing.” Re-enter Scrubby (obviously safely down from the rigging) reassuringly stating, “Oh no, sir, we won’t do that.” In a marvelous moment, he shuts down Lingley’s demand to see the captain by informing him that “he left long ago, sir.” True to character, he brushes aside Lingley’s threats, telling the group that he’s seen many “passengers” get angry at first. Urged by Tom to repeat that everyone there is “quite dead,” they almost accept this when it comes from the man who seems to know everything. That is except for Lingley of Lingley Limited, who proclaims he will “get out of it.” Scrubby—kind as always, even in the face of belligerence and ridicule—tells them this is impossible “until after the examination,” unwelcome new information that sets Lingley off again. But the steward firmly asks that the ladies find out independently so they don’t get “hysterical.” Lingley can’t take it in and appeals to Duke, who suggests they pray, which is met with no enthusiasm. Scrubby tells them there’s no danger and gamely carries on with the foreboding that it’s all simple until they meet the examiner. Lingley calls him a “lunatic,” afterward bizarrely bragging that he alone has “solved the whole thing suddenly” (prompting the first remark from Henry during the entire scene, “Have you?”). Again thinking only of himself, he reveals that he’s asleep. And that, luckily, he can “get out of it.” Scrubby solicitously goes to him, presumably to make him comfortable in his room for a bit. Robert Milton’s staging here is evocatively exactly right: Duke alone at a center table, Prior at a table by the wall (often with his head in his hands or leaning back for some support), Lingley pacing around, Scrubby doing his work as he talks to them, and Henry hanging on to the room divider, eventually gravitating to leaning on the seat that Tom vacates as he drifts to the bar. Duke turns down Prior’s offer of whiskey “in case we meet anyone.” Tom expresses his regret for being a “rotter” and references “a novelist once who said never too late to mend” and “the Great One … in the Bible.” Tom Prior cannot remember what He said. (In Sutton Vane’s play, Prior names the novelist, calling him “rotten.” Charles Reade wrote a book in 1856 entitled It Is Never Too Late to Mend. And undeniably, “the Great One” is Jesus Christ. Screenwriter J. Grubb Alexander omitted Reade’s name and the “rotten” adjective, which made sense since the novelist was probably pretty obscure by 1930. The title of the book is significant.) Duke replies with more nonconformist theology, “it doesn’t really matter very much what either of them said.” and goes on to state that what Tom had to say was more to the point. (Understandable when referring to nineteenth-century novelist Reade, but not so when a clergyman states it doesn’t matter what Jesus said!) Duke and Prior go out on deck to talk after Henry declines an invitation to join them. Relentless, Tom Prior is compelled to talk to the unwilling Henry again and maintains that he had to have known about them being dead, or he couldn’t have left Ann alone on deck. Stubbornly, Henry declares that he knew nothing and doesn’t know anything now. After Prior leaves, Henry and Ann discuss their “secret” and how others know about it. Henry thinks the Examiner might separate them.

The play opens its Act III with things set up for a meeting. Lingley is running it to determine whether or not they are dead and how to deal with the Examiner if they are. None of this is in the film. Although acceptable in a play, having a group gathering just before interferes with getting to the real meeting—with the Examiner. If they are dead, Mr. Lingley wants to represent the group himself. Duke’s character goes off the rails in this act. He runs sweepstakes as to when they’ll land, calls Mrs. Cliveden-Banks “Banky,” insults Lingley, and tries to tell an off-color limerick. None of this would have strengthened the film. It is far better to keep Reverend Duke a flawed yet pure soul.

Another solidly cinematic addition to the film is Scrubby knocking on doors, “We’ve just sighted land, sir,” so we get fleeting glimpses of three rooms with Prior, Lingley, and Duke. Cut to the ship (appearing physically different every time we see it), complete with muted foghorn and onshore structures that resemble crystal stalagmites out of a dream—or nightmare. The steward enters through the center doors, already surmising they have questions about the Examiner. He cautions Lingley to leave “the approaching” to the Examiner, which sane advice Lingley of Lingley, Limited will ignore. Segue to some of the most poetic lines in both play and film. Duke asks, “What’s he like?” Scrubby mystically responds,

He’s the wind and the skies and the earth. He knows the furthest eddy of the high tide up the remotest cove. He knows the simpleness of beauty and the evilest thoughts in the human mind. He’ll know all your evil thoughts.

After Scrubby excuses himself, Prior wants to “get away,” stunned that the “judgment” should be “in the smoke room of a liner.” Duke retorts why it shouldn’t be there and wonders aloud if they have ever thought about the where, when, and how before. The film sensibly retains Prior’s extreme agitation and the Reverend Duke acceding to Mrs. Midget’s request for a prayer. “Gentle Jesus, meek and mild, look upon a little child—children—and make me a good boy. Amen.”

Scrubby re-enters, announcing the Examiner. (At Ann’s urging, she and Henry hide.) Their Examiner is Thomson, who Duke appears to know very well, except he’s unaware of his former colleague’s status. Sutton Vane describes him as “jovial.” [The Examiner is Dudley Digges, an Irish stage and film actor who would follow up Outward Bound with the kindly drug-addicted Doctor Saunders in The Narrow Corner (Warner Bros. 1933,) adapted from a metaphysical Somerset Maugham novel also with Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. Next would be his Chief Detective, in The Invisible Man (Universal 1933).] Duke tells him how worried he is, and Thomson reveals why he is there. Gently, he reassures his old friend that he has a room for him in his own house and heartens him immeasurably by promising that he still loves the job he loves.

In my Father’s house, there are many dwelling places … And if I go and prepare a place for you, I will come back again and take you to myself, so that where I am, you also may be.

John 14:3

Uninvited, Mr. Lingley runs on even after Thomson instructs him to “go away” several times. Finally, he does go, and Mrs. Cliveden-Banks cluelessly approaches Thomson with her calling card. After these characteristic but unwelcome advances, Scrubby assists the Examiner with seeing the passengers in order, starting with “the officious one.” Lingley brazens his way through it, mentioning “enterprise,” which got him what he wanted. The Examiner rightly labels it “dishonesty,” which Lingley deems a lie. This ends his case with no possible appeal, even after he asks for a “second chance,” which Thomson stingingly reminds him that he never gave to anyone else. Plain Lingley now dejectedly departs to “suffer” as he “made others suffer.” Duke pities him, but Thomson resolutely states it “must be done.”

Mrs. Cliveden-Banks is next, even though an on-the-edge Prior tries to jump his place in line. At any rate, her session reveals the snooty, unrepentant woman to have been unfaithful to her good husband (Benjamin nicknamed “Bunny”) and to have been a “bad harlot.” Thomson proffers a villa with servants, but to get them, she’ll have to be a real wife and accept that all her sketchy behaviors will be revealed except to Colonel Cliveden-Banks, who will have been allowed to forget. She dislikes these terms, especially dealing with her husband’s loving eyes, and flounces off, deliberately mispronouncing Thomson’s name and slinging a vicious parting shot, “You swine!” In the play, the Examiner wants to “fumigate” the room after Mrs. Cliveden-Banks departs.

Tom Proctor does take his turn next and gets a drink from Thomson. He begs to be dead—blank but is told that he must go on, presumably (to his horror) without drinking. Unbidden, Mrs. Midget apologetically interrupts and talks about how kind Tom was to her. (Thomson undoubtedly is aware of that but allows her to continue.) She excuses his imprudent misconduct, also mentioning there was a girl who “chucked” him, eventually arriving at her dearest wish. Mrs. Midget wants to be Tom Prior’s housekeeper to look after him. The Examiner tempts her with a little cottage and garden by the sea, but since Prior is not yet on her “plane,” the good woman will forsake this charming little paradise to care for him back in “the slums.” Tom objects to her kindness with, “I’m not worth bothering about,” impressing Thomson with his “humility.” He goes off then, promising to at least try. The Examiner bids farewell to “Mrs. Prior,” which upsets her because she doesn’t want Tom to know. Both men swear they’ll never reveal this fact, allowing the happy mother to join her son and look forward to “ ‘Eaven.”

Reverend Duke has attempted to help Henry and Ann all this time. Thomson won’t see them because they’re not on the passenger list. Scrubby discloses that they are “half-ways.” “Not yet, my children.” Duke doesn't understand but accedes to the Examiner and follows him out.

Bewildered, Henry and Ann remain with Scrubby as the ship moves away. Then Henry hears breaking glass and Laddie’s bark and feels Laddie’s touch on his hand.

Screenwriter Alexander switches Ann’s soliloquy to Henry, which works better.

You see, I love you.

I love you so much.

I love the way you walk,

The way you hold your head. I love you. I love your mouth.

Henry tells her to “Never let go,” but Ann is puzzled as to why they aren’t closer. “I thought we would be when we’re dead.” She also suspects they were “wrong,” to which Henry almost angrily objects. He hears Laddie’s bark again and is eager to go to him. Scrubby asks about Laddie but constantly exhorts Ann to stay close to her love. An increasingly torn Henry wants to know what will happen to them, and Scrubby—from his 5,000-plus trip experience—says that because they’re “half-ways,” they’ll go on “backward and forwards—forwards and backward.” Scrubby is also a “half-way,” but he’s” been allowed to forget.” Suddenly, it dawns on Henry what a “half-way” is.

They committed suicide, and it “wasn’t right.” Duetting, Henry, and Ann tell Scrubby they’re not married (which, of course, he has always known). They talk of Henry’s loveless marriage and how they came together. Not regretting their attachment but their lack of courage, Henry says, “Our future here isn’t Hell. It isn’t Heaven. It’s past imagination.” Scrubby sums it up. “It’s eternity.” Henry goes on deck.

Ann asks why people aren’t “kinder to each other.” Scrubby says it’s probably because being unkind is more “natural.” He gets Ann reminiscing about what she liked about being alive. “There were so many things. The scent of the earth after rain … and all clear things, like water.” (Ann identifies with water, being a transparently honest, empathetic person herself.) Scrubby tells her he knows she “wants the earth again … the sea will send your wish to the clouds, maybe.” He adds that he hopes the earth “will send back her kindest regards and best wishes.” Scrubby and Ann have an instinctive camaraderie, but still, he cautions that Henry is drifting further away and then, “He’s gone…he lives again.” Saved by Laddie breaking the window, he had to return without Ann.

Scrubby says, “A week. A century. A moment. There’s no time here.” Helen Chandler’s heart-rending Ann is agonizing to watch as she twists and kneads her hands—nearly fainting—imploring her absent love to tell her where he is and to put the wedding ring (that’s not a wedding ring) from the mantelpiece on her finger. She begs, “Don’t leave me alone forever!” Astonishingly, Scrubby hears something on the deck, and Henry does appear. “Be quick, dear … be very quick … there’s such a lot to do, my love, and a little time to do it in.” They disappear into the fog, and we hear an emergency siren and see rubberneckers on the street back in London. Walter Kingsford’s Bobby again shows up, criticizing poor Laddie (this time for breaking the window.) The good dog is being held by a compassionate young girl, calling him a “hero.” Henry and Ann have been given a second chance.

The playwright’s novelization of his immensely popular play was published in 1929, but it’s a depressing read from start to finish. (Vane, Sutton, Outward Bound (66-66 A Great Queen Street, Kingsway, London, W. C.2, 1929.) Various pages. Jock (Laddie) narrates the first chapter of the movie. The couple adopted him from the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home (actually founded in 1860.) Together, Henry and Ann decide to take their own lives (after Henry decides that his legal and unloving wife will never divorce him and may never even die!). It’s cold, but Henry puts Laddie outside to keep him away from the soon-to-be gas-filled room.

Subsequent chapters are no better. We see Lingley at his wedding, where he thinks the cake should have black frosting! (A deal was made: his money, her social position.) Eventually, he goes bankrupt, is deserted by his business associates, and has a fatal heart attack while sitting at his desk.

Next is Tom Prior, who has indeed been “sacked” by Lingley’s firm. He blows through his severance pay on alcohol and chocolates for his fiancée (Popsy), who ditches him. He drinks himself silly, and it’s unclear if the train he wants crashes or if he falls under it to the tracks. But Tom does hear celestial music. (This is only the third chapter!)

We are told very little about the passing away of Mrs. Cliveden-Banks except that it was “peaceful.” Still very rich, she remained in London while her husband was in India, where he preceded her in death. Without any relatives, she appears to have left an entire fortune to her servants.

The Reverend William Duke dies from exposure after saving a girl from drowning. (She turns out to be a prostitute, a fact which his superior unpleasantly brings up, hastily adding that Duke couldn’t have known that about her.)

On the same night of Tom Prior’s death, his mother, Mrs. Midget, becomes “dangerously ill” after never being sick before. Stopping at a side-by-side ladies and gentlemen saloon, she hears her son, Tom, ordering drink after drink. Barely dragging herself home, she hopes to make the approximately two-hour trip to Margate for a rest from her charwoman jobs, but she is ominously feeling weak and delirious. Sadly, the poor woman thinks she should start now rather than the next morning to be on time for public transportation. Mrs. Midget doesn’t make it. The door of her flat opens on its own, and soon enough, she finds herself on board a ship where she is settled cozily with hot tea in a cabin with clean bed sheets. The steward’s name is Scrubby.

After getting all this information, we continue with Scrubby, welcoming all seven passengers to the ship. Just as in the book, the characters talk, drink, argue, and eventually face the Examiner (except in the novel, he’s Thompson, not Thomson.)

Outcomes are the same, but the novelization adds a tragedy for Henry and Ann. Sutton Vane’s original play ends with Henry returning for Ann; it does not show them back in the suicide flat. The 1930 film assures us that the couple was saved by Laddie crashing through their window. (While still onboard the unearthly liner, Henry hears breaking glass and a dog barking.) We see Laddie cradled by a kindly neighbor and know he will be all right. But the book has a denouement that should never have been seen in print. Jock (Laddie in the film) bleeds to death from the broken glass. The very last sentence flatly, emotionlessly tells us that he dies. What?

Author, editor, and writing coach Cara Lee Lopez said this in a SlackJaw post from September 24, 2020. “Never kill a dog or cat in your novel. You’ll lose readers, and you’ll get hate mail.” There’s no information about Mr. Vane’s mail after publishing his novelization.

THE SHIP THAT TRAVELS THE SEAS BETWEEN HEAVEN AND HELL.

DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS, JR. AND HELEN CHANDLER

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com