Hans Salter and House of Frankenstein: Hitting All the Right Notes !

Why the musical score for House of Frankenstein might be the best in the Universal series. 1 HR 11 MINS Universal

HORROR/SCIENCE FICTION

written by Barry Atkinson

5/13/20259 min read

Let’s face it: film music as we once knew (and heard) is dead in the water. Modern-day movies cater to the visual, not the aural; the younger generation of filmgoers do not give a hoot or appreciate who wrote the soundtrack to the latest 3-D blockbuster, what passes for a score, and all that it stands for, simply a mass of swirling tuneless noise behind the requisite explosive action. This wasn’t the case decades ago. Composers were seen as an essential ingredient of the filmmaking process, their scores embedding themselves in the psyche of moviegoers to such an extent that aficionados of a certain age can still recall them.

Take one Hans J. Salter. Born in Vienna in 1896, Salter studied at the Vienna Academy of Music, immersing himself in classical composers, before working for the Berlin State Opera House and moving on to Germany’s Universum Film-Aktien Gesellscaft (UFA) film studios to compose music for early talkies.

Emigrating to America in 1937 to escape Hitler’s burgeoning Third Reich regime and the terrors it represented, Salter was taken on by Universal, where he worked for 30 years, primarily in the fields of horror, science fiction, and Westerns, composing and contributing to over 450 movie soundtracks. Nominated for six Oscars and receiving one for the Executive Achievement Award in 1982, Salter’s music could lift a Universal low-to-medium budget production to untold heights; he’s famous for his mesmerizing scores (created by musical committee at Universal consisting of several composers) to The Wolf Man (1941), The Mad Ghoul (1943), Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), The Mole People (1956) and The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957), as well as numerous outstanding Universal Westerns of the 1950s such as Apache Drums (1951), Bend of the River (1952), and Last of the Fast Guns (1958); his music for the Errol Flynn swashbuckler Against All Flags (1952) is particularly potent.

As an example of Salter at his very best, look no further than his composing efforts on House of Frankenstein, released by Universal in 1944. Salter was no stranger to the company’s Frankenstein franchise, having scored The Ghost of Frankenstein (1942) and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943); the latter’s title music is an absolute sonic blast of sound. The sixth in the series saw Salter, assisted in part by German composer Paul Dessau (he had emigrated to America in 1939 for the same reasons as Salter), producing a score that verged on the classical/operatic at times, thus elevating House of Frankenstein to a near combination of horror and tragic opera. Fanciful? Not if you catch the movie and listen to Salter’s fantastic tonalities, sounds that underscore not only the devious activities of Boris Karloff (Dr. Gustav Niemann) but the doomed love triangle featuring hunchback J. Carrol Naish (Daniel), infatuated with Gypsy girl Elena Verdugo (Ilonka), who in turn has fallen for the morose charms of Lon Chaney, Jr., playing the cursed Larry Talbot, the Wolf Man.

Composed of 34 separate musical chapters, Salter’s score for House of Frankenstein was completed in just over two sleepless weeks; such was the stringent timetables set out by Universal during that frenetic period of filmmaking, this incredible feat just went to prove how immensely talented people like Salter were in those heady Hollywood days, able to adhere to strict deadlines and still produce the required goods. Alongside Franz Waxman’s score for Bride of Frankenstein, Salter’s tonalities used to back up this “company of accursed characters” is so highly thought of today that the entire piece of music is available on disc; not many horror scores can lay claim to that accolade. And like many memorable movie soundtracks, it can be enjoyed as a piece of music to be listened to without viewing Karloff’s antics in Erle C. Kenton’s outrageous fun-packed “menagerie of monsters” concoction shot at a breakneck speed of 71 minutes. So, step by step, we’ll go through the entire movie in tandem with Salter’s music and finally agree that, in this instance, the result was a perfect marriage of classical movie scoring and monster mayhem that very few horror pictures could live up to.

Following the Universal logo, the powerful central title theme (one minute, 27 seconds) kicks off, first in bombastic style, then undergoing several changes in key, segueing dramatically into a series of near-tragic chords before reverting to rousing notes, and Salter incorporates a clutch of codas in homage to Beethoven’s doom-laden 5th Symphony. An aural barrage of low notes accompanies Boris Karloff, the “would-be Frankenstein” and hunchback J. Carrol Naish’s escape from 15-years’ imprisonment when thunder and lightning cause the walls of their cells in Neustadt Prison to collapse, Karloff subsequently taking on the guise of Professor Bruno Lampini (George Zucco plays him), who Naish has strangled. Lampini’s Chamber of Horrors show features, as its chief exhibit, the coffin and skeletal remains of Count Dracula (John Carradine), with a wooden stake protruding from the rib cage. In Reigelberg, Karloff exhibits Dracula’s skeleton to disbelieving burgomaster Sig Ruman, daughter Anne Gwynne, and husband Peter Coe, then, when the curtains are closed, he removes the stake, reawakening the vampire, his bones materializing into flesh and blood: “I will serve you,” Karloff tells Carradine, but at a price. Karloff wants the burgomaster dead, so the bloodsucker introduces himself to Ruman’s family as Baron Latos, instantly homing in on delectable Gwynne, whom he desires as his new bride; a ring with the Dracula crest is placed on her finger to cement the unholy “relationship.”

Up until this point, Salter’s incidental music has remained relatively low-key. It kicks in with a vengeance during the 13-minute-long Dracula/Latos segment, an eerie, unsettling organ-based undertone that highlights Carradine’s shadowy movements; Salter utilizes a few motifs found in 1943’s Son of Dracula: Carradine changes into a bat, murders Ruman by drinking his blood, and promises to visit Gwynne at night. “A strange and beautiful world in which one may be dead yet alive,” intones Gwynne under Carradine’s spell. Lionel Atwill’s police force is summoned to investigate Ruman’s demise (“Two puncture marks to the throat”) as Carradine flies off in his coach, Gwynne, in a trance, on board. Karloff and Naish, in the two caravans, are ahead of Carradine, the police, and Coe, behind, as the music rises to a crescendo, adding to the excitement of the chase. Naish throws Dracula’s coffin out of the caravan, and Carradine, watching in alarm, sees his home topple into a ditch. His coach swerves and crashes, the vampire crawling over and reaching for his coffin, where he dissolves in the rays of the rising sun. Kenton ends what can be classified as part one of the movie with a sentimental close-up of Gwynne and Coe in each other’s arms, Salter’s music rising to an almost romantic climax.

In the 26th minute, we now get down to the nitty-gritty, although the Dracula/Latos episode isn’t anywhere near as draggy as some critics might suggest. But it’s from here that the inventive action takes off, and the composer’s imaginative arrangements are given full rein to cover the many fatal events to follow. Naish becomes the narrative’s central focus, the caravan trundling towards Visaria (or Vasaria) and entering a Gypsy camp where Elena Verdugo performs an uninhibited dance routine to the composer’s high-spirited, Russian-themed music. Lashed by the Gypsy boss for not handing over her takings, Verdugo is rescued by Naish, who half-throttles the brute, taking her into the caravan (cue for a rather sweet leitmotif). Spotting his deformity, the girl turns her face in fear and sorrow, Naish pleading, “But you will talk to me sometimes, won’t you?”

In the village of Frankenstein, Karloff and Naish, told by the authorities to get moving, scramble into the vaults beneath Frankenstein’s ruined castle in search of the Frankenstein records; Salter’s organ-based music creates a dreamlike air when the pair enter an icy, glacial cavern, the tonalities taking on a more menacing note as the Wolf Man and the Frankenstein monster are found preserved in the ice. “The undying monster! The triumphant climax of Frankenstein’s genius … and the Wolf Man. We’ll set them free. Build a fire,” Karloff orders Naish, snatches from The Wolf Man’s soundtrack used as the hairy one thaws and transforms into Lon Chaney. “You’ve brought me back to a life of misery,” moans Chaney as a thank you, the Frankenstein journal discovered behind a large block of stone.

In the caravan, Naish is charged with tending to the monster; Chaney is now the driver and attracting the attention of Verdugo, which doesn’t please Naish one bit; the hunchback loves the girl, the music both melancholy and semi-operatic, pointing out Naish’s inner turmoil. “Why are you always so sad?” she asks Chaney, wondering why he’s so non-talkative and downcast. Chaney replies, “No one can help me.” Visaria is reached: Karloff, in a montage of shots enhanced by a myriad of differing notes from Salter, reorganizes his laboratory. Chaney complains that he wants an operation at once to cure him of his curse. “The moon will be full tonight,” he warns Karloff. Naish wants his brain placed in Chaney’s body; Karloff has other ideas, abducting town dignitaries Frank Reicher (Ullman) and Michael Mark (Strauss), two old enemies of his, and relieving them of their brains in his lab. “Ullman’s brain in the skull of the Frankenstein monster … Strauss will get the brain of the Wolf Man,” Karloff chortles, ignoring Naish, who begs, “Master. Will you give Talbot’s body to me?” the scientist callously brushing him aside.

Now, Salter’s score is in overdrive, ranging from tragedy to furious madness. Verdugo learns from jealous Naish that Chaney is a werewolf: “You love him, don’t you? The five-pointed star—the pentagram … he’s a werewolf,” he says to the Gypsy girl who mutters, “The sign of the beast. You’re lying; you’re jealous; I hate you! You’re mean, and you’re ugly!” Naish, crestfallen and broken-hearted, walks over to the semi-conscious Frankenstein monster (Glenn Strange), strapped to a bench, and whips him savagely, sobbing, “She hates me because I’m an ugly hunchback,” the music rising in tempo, swelling to a demented, almost furious racket, reflecting Naish’s agony (which we feel) and the dreadful events shortly to follow.

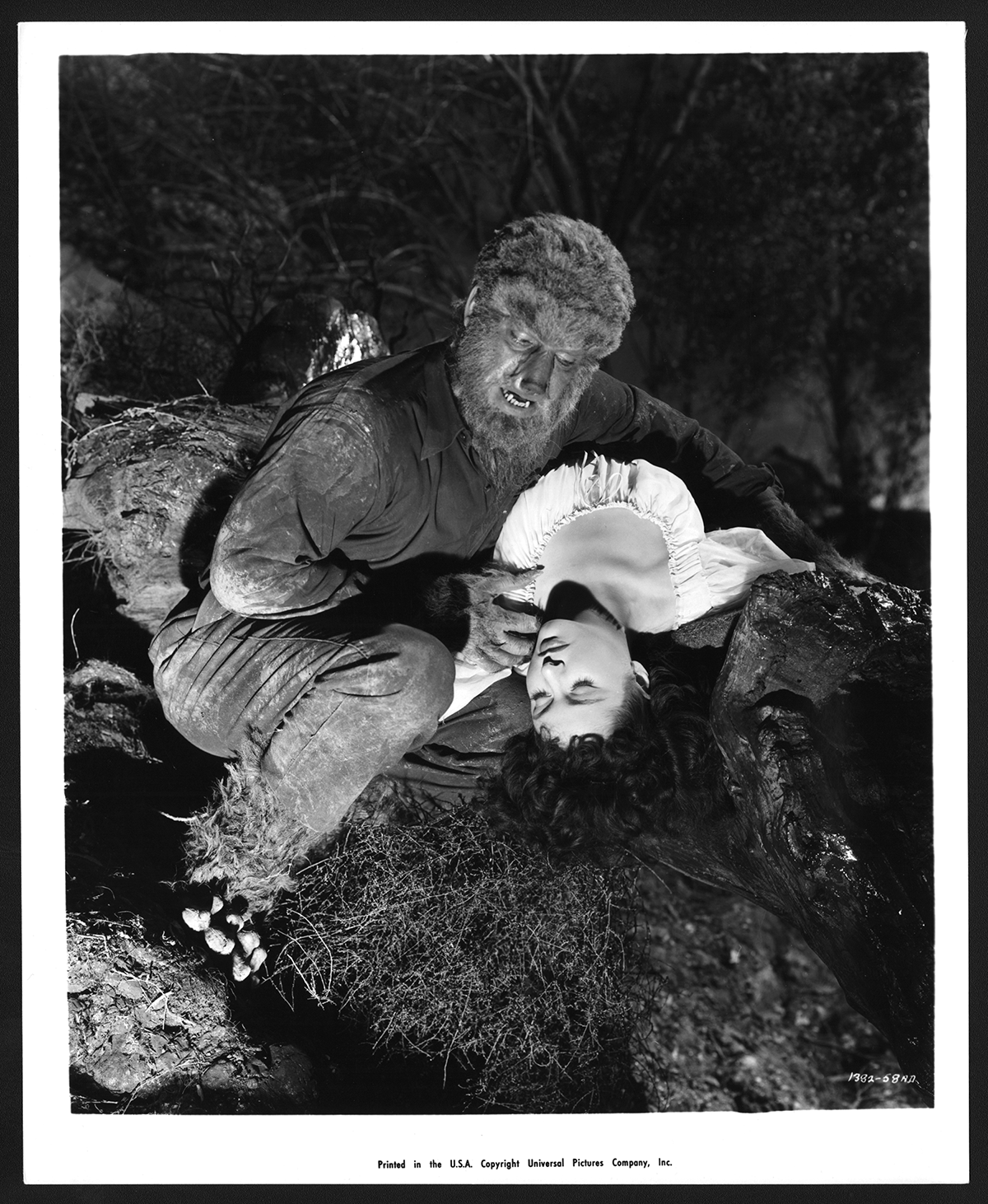

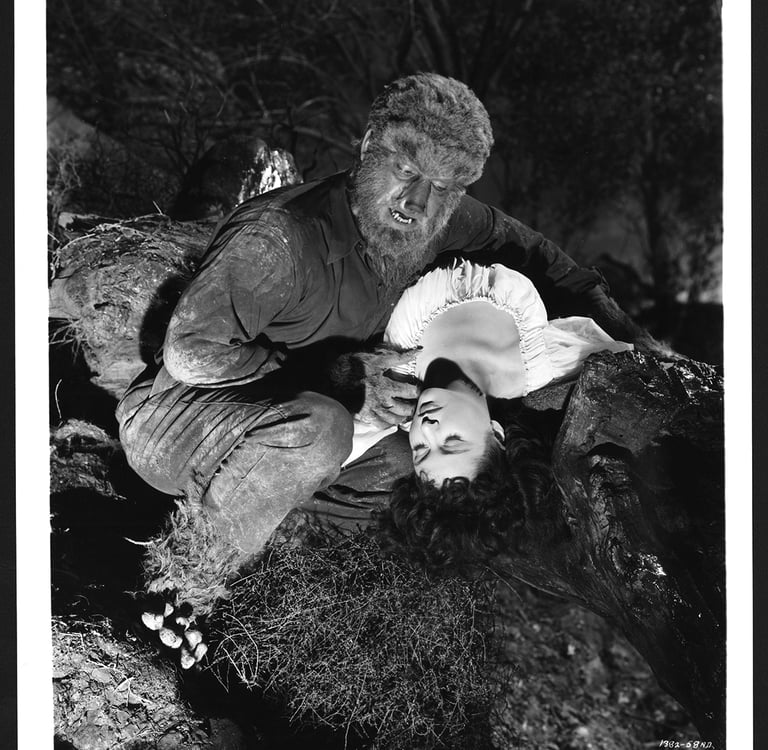

The chaotic, riotous finale commences with the full moon rising; Chaney runs out into the woods, director Kenton panning over footprints that change from human to animal, one man later found mauled to death, his jugular torn open. Hunting parties are split into three to find the werewolf killer, Verdugo, and Chaney, cuddling each other. “You know,” he asks her. “Daniel told me. I might even kill you,” he tells the distraught lass. Salter intensifies his “tragic music” to the full as Verdugo reluctantly says, “Only death can bring us peace of mind … killed by a silver bullet by the hand of someone who loves him enough to understand.” She departs to fashion herself such a bullet. In the laboratory, electrical impulses revive the monster as the House of Frankenstein enters its final phase of horror tragedy. Armed with torches, the villagers observe flashing lights in Karloff’s lab. The moon rises, and Chaney, facing himself in a mirror, morphs into the Wolf Man, hurling himself through the French windows and grabbing Verdugo by the throat; the girl shoots Chaney as she dies, the two bodies sprawled in the dirt. Naish, stricken with grief, takes her body to the lab, placing it on a table, focusing on Karloff. “Master, the only thing I ever loved. It wouldn’t have happened if you’d kept faith in me. I served you well, Master. Remember Lampini? Strauss? Ullman? Now you’re going to join them.”

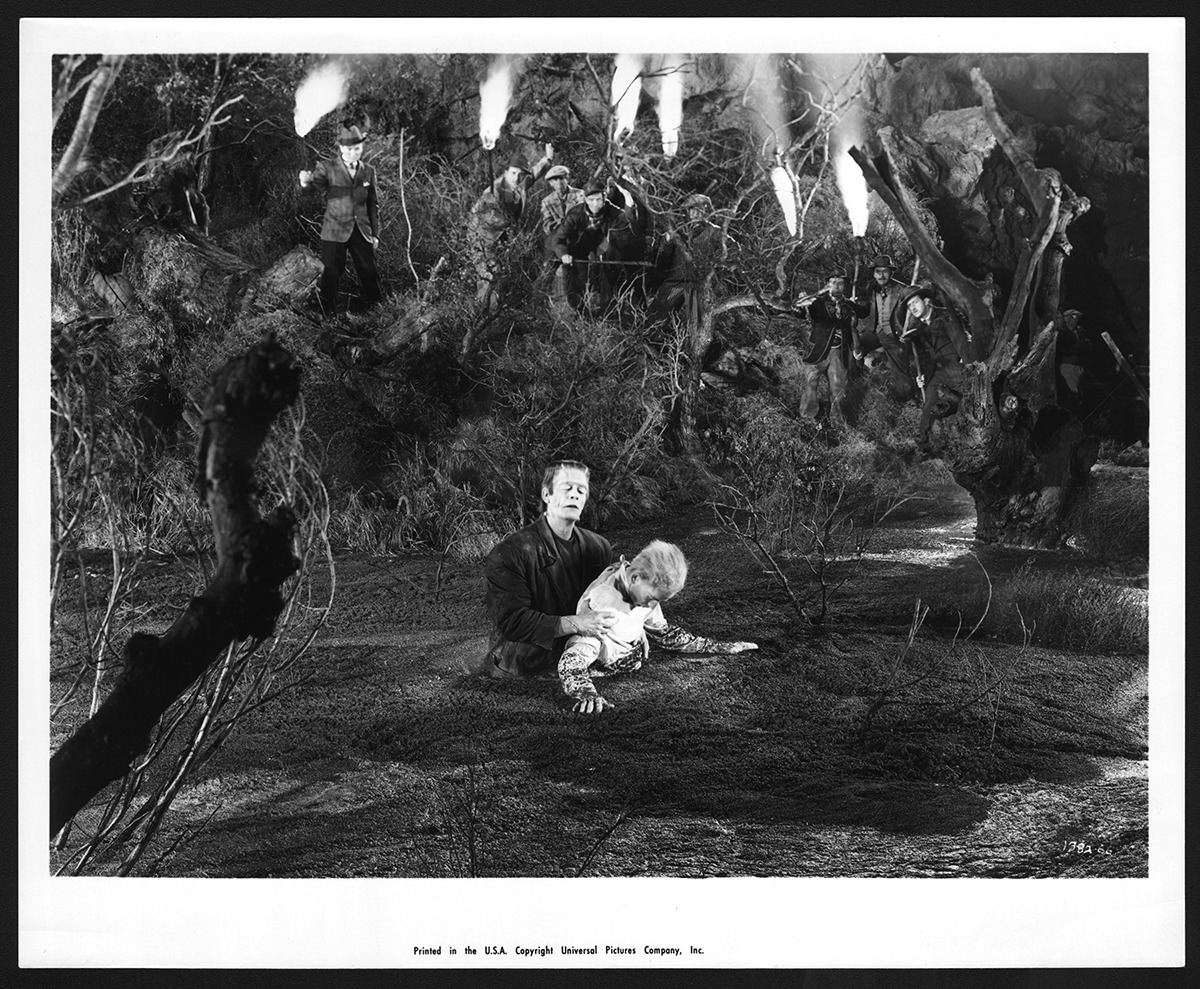

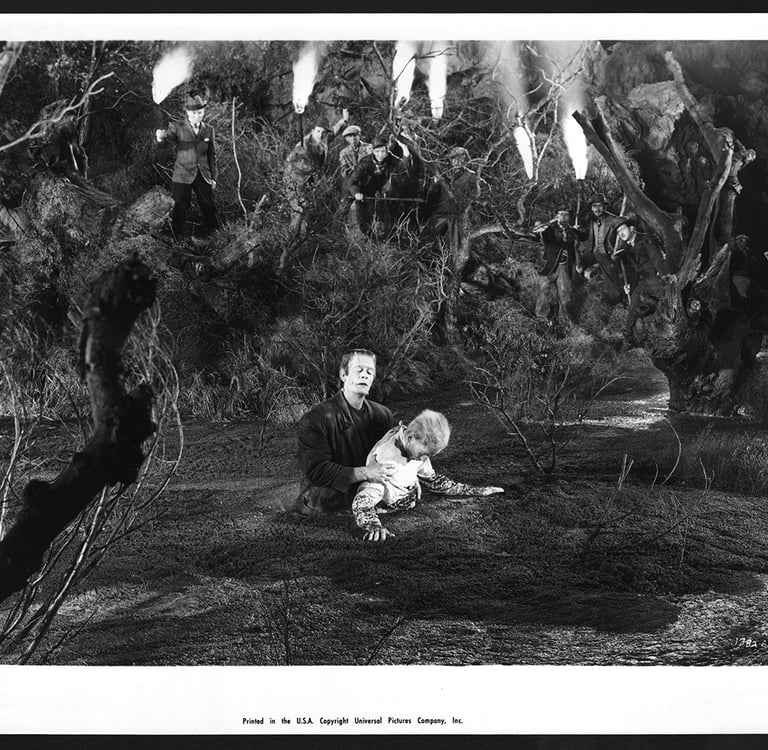

Half-strangling Karloff in a rage, Salter’s thumping, three-note “Frankenstein monster” motif comes into play as the monster lumbers across the lab into view, grabs Naish, and hurls him through the skylight to his death. Picking up a dazed Karloff, the monster is forced to retreat by the villagers, armed with torches, staggering out of the house into swampland to the sound of Salter’s pounding score, where the marsh grass is set on fire. “Not this way? Quicksands! Quicksands!” croaks Karloff as the monster backs into a bog, dragging Karloff under to his doom, Salter’s music reaching a calamitous conclusion. This is one horror film in which every principal character dies in miserable circumstances.

What a pity a composer of Salter’s caliber wasn’t asked to score the follow-up, House of Dracula. Although not a bad effort, it pales beside the utterly flamboyant shenanigans here, faultlessly acted by the cast, that make House of Frankenstein such a joy to watch over 70 years later. Yes, the horror genre meets grand opera, thanks to Hans J. Salter’s richly textured Symphonie Fantastique, a classic Universal horror score (the best of the Frankenstein series and maybe the finest of any Frankenstein film) that seamlessly wove music from his other films into a brand-new soundtrack, one that ebbed and flowed, breathing life into the (among fans) revered visuals, thus ensuring that what you saw on the big screen was bolstered by what you heard. Salter’s score for this Universal classic horror romp has stood the test of time well; it’s one that all students of film music should listen to and learn from. To quote a well-worn saying, they certainly do not make movie scores like this anymore.

LARRY TALBOT (LON CHANEY, JR.) ATTACKS THE GYPSY GIRL (ELENA VERDUGO)

THE FRANKENSTEIN MONSTER (GLENN STRANGE) DRAGS DR. NIEMANN (BORIS KARLOFF) INTO THE DEADLY SWAMP.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com