Frankenstein 1970

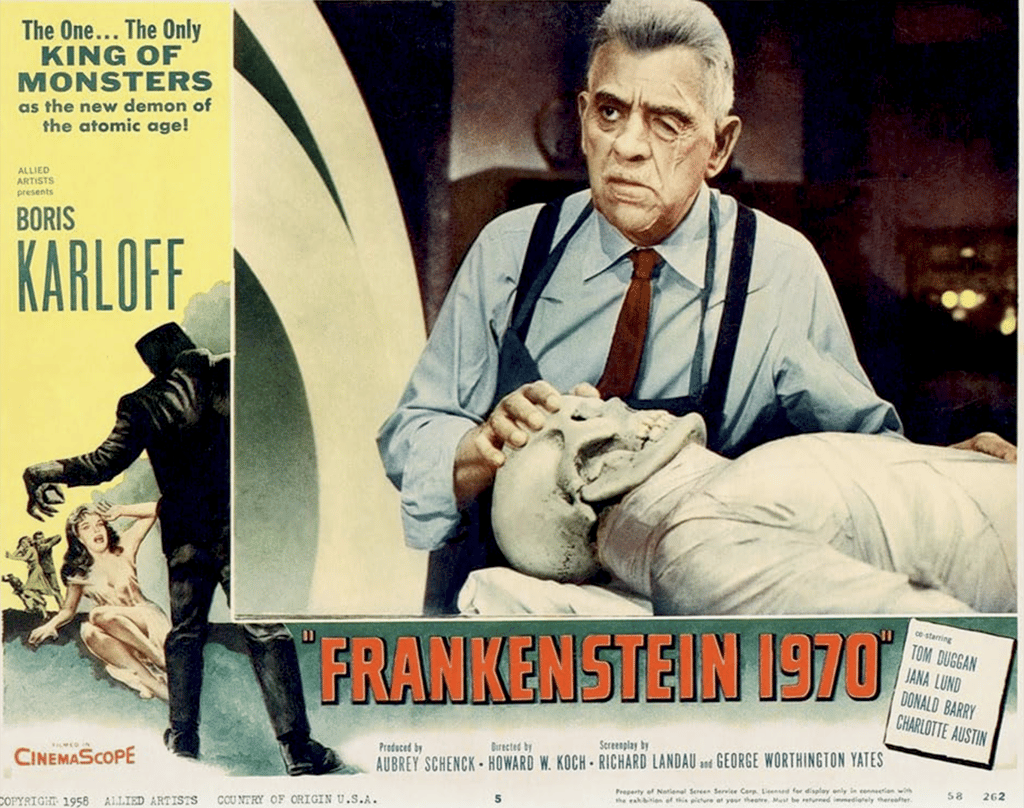

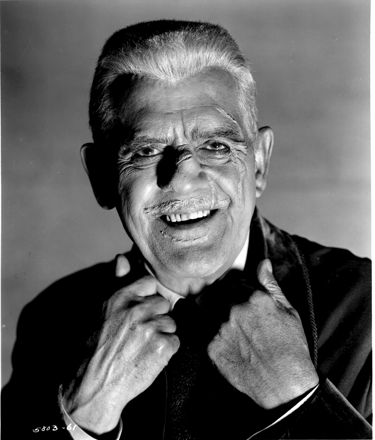

The Universal Frankenstein series enters the 1950s with icon Boris Karloff playing the Monster creator, Victor von Frankenstein. 1 HR 23 MINS Allied Artists 1958

HORROR/SCIENCE FICTION

written by Gary Svehla

6/24/202513 min read

The 1950s were the era of the “B” picture, the double-feature, and in their splendid low-budget glory, a generation of adolescents was entertained by monsters, aliens, and various blobs. What about the revered Frankenstein series, initiated by Universal? After the classics of the 1930s, we had the cheaper monster rallies of the 1940s, and now in the 1950s, we had Frankenstein’s Daughter, I Was a Teenage Frankenstein, How to Make a Monster, and Frankenstein 1970. While we could tolerate teenage werewolves and generic vampires, bastardizing such an icon as Frankenstein and his Monster was almost sacrilegious. Over the years, there have been divergent opinions on Frankenstein 1970, both good and bad, that this film deserves an in-depth analysis of what exactly works and what doesn’t. Rather than declaring it good or bad, we can identify the flaws and superlatives, and ultimately determine whether the film succeeds. Bottom line: Is it worth our hard-earned money?

THE BAD:

When among themselves, the movie crew tries to sound hip and current, contrasting Victor and Gotfried’s Old World style and Continental manners. Looking at such scenes today, the movie crew seems to be caught in time, out of sync, and unrealistic. “Yeah, we’re playing over Europe, the United States … we’ve got a good thing going with the national magazines … they are going to the Frankenstein party here in the castle after the show. They got a whole thing going … goblins all over the place … yeah, goblins. We are running a horror contest … beautiful goblins from all over the country …” When the movie isn’t worried about goblins, the movie crew can be found in brief sequences in-between superior Boris Karloff or murderous monster sequences, offering the opportunity for the audience to raid the concession stand while members of the crew try to get into starlets’ pants.

In most Frankenstein movies, the pre-living creature is covered in gauze from head to foot: Frankenstein (1931), Bride of Frankenstein, Curse of Frankenstein (1957), and Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), among others. But after the recreation process, they are unwrapped and emerge as distinct monsters. A generic wrapped fiend is not a unique-looking and fleshed-out personality. Imagine if Boris Karloff played Frankenstein’s Monster completely covered in white gauze? Would any of his sequences play as effectively? Would Michael Gwynn be able to demonstrate the deterioration of his creation so proficiently if his body were hidden from the audience?

This is precisely what was done in Frankenstein 1970. The effectiveness of seeing a giant glazed monster on the slab piqued our interest in exploring the fully exposed monster. But once the creature goes on a murder spree, completely covered except for slits for eyes-to-be, it is a huge disappointment. Instead of a character and a fully scripted creature, we only get an undistinguished hulking monster without character or personality.

And what is particularly disappointing is that the revised Frankenstein’s Monster shown in the opening scene was 100 times better than our giant mummy shown elsewhere. In the first three and a half minutes, this new interpretation of the Monster evolved from the 1930s' Monster, reimagined for the latest generation. Even without showing the front of his head, audiences immediately recognized this figure as Frankenstein’s Monster, complete with suit, clunky shoes, moving as if crippled, with frozen arms outstretched. That was an imaginative concept. But after that moody scene, the central concept used for Victor von Frankenstein’s creation was just that of a giant, generic fiend. Under all those wrappings might as well be a monster from outer space. Even the Hammer Frankenstein series had unique creations in every movie, and as we all know, a Frankenstein movie without an effective monster is a waste of time. It’s like Shakespeare’s Tragedies without superb villains.

THE GOOD:

The opening scene, shot in CinemaScope and black-and-white (such wide screen monochrome was becoming a fad in the 1950s with Return of the Fly, The Alligator People, and now Frankenstein 1970), may be the best sequence in the movie, showing a young lady running, being pursued by a Monster wearing metallic boots, crouched downward, flexing his arms and hands outward, moving in herky-jerky motion (remember Universal copyrighted the Frankenstein Monster’s makeup, and Carl Guthrie’s photography always cut his head off in the widescreen frame, unless shot from the rear). Screaming as she runs through the swamp, the Monster follows her moving as though crippled. Paul Dunlap’s music crescendos as terror intensifies. A close-up of the Monster’s hands reveals they are contorted and twisted; the half-human emits guttural growls. The woman falls, allowing the Monster to get closer, as she runs into the dense fog. The woman then runs into the swampland water, and the quickly approaching Monster, moving as though suffering from a bad case of arthritis, approaches. The Monster lunges at her, chokes her, and places her head underwater. Suddenly, we see a film crew, the director Douglas Rowe (Donald “Red”

Berry) call an end to the shot as crewmembers observe. The first minutes offer an updated view of Frankenstein’s Monster, one remodeled for the 1950s, approximating the original make-up concept. With the dark swamp locale, the film never gets better than this opening sequence.

A man with an extended crew cut, his back toward the audience, says: “How could you inflict these people on me, Goffrey! No privacy. I cannot think, I cannot work. I’m completely overrun. My castle. My grounds !” His manager/financial assistant, Gofffried (Rudolph Anders), reminds him of the need to purchase an atomic reactor and how he said he would do anything for the money. And Gottfried reminds him he has been spending money like a government. The then-revealed Victor (Boris Karloff) yells, “It’s my business,” but Goffried declares it’s his business too; if he's to manage his affairs, he must have something to manage. Goffried states he has sold all Victor’s artifacts to finance his passions. Victor changes the subject, moving to his aquarium, “My fish, they are hungry beasts. They struggle for existence just as fiercely and ruthlessly in their world as it is in ours.” Goffried then mentions the torture Victor received during the war by the Nazi’s. And Victor slowly recalls.

In almost a snickering tone, Victor states: “They believed in one thing, I believed in another. But they were running the country. That was my misfortune.” Goffried states, “But you won!” And Victor retorts, “I won. You’re thinking only of my surgeon’s hands. They were too clever to do anything to them. They needed them for the unholy operations that I performed for them. But what they did to the rest of me … my body.” Goffried adds, “But you did not give them what they wanted. You didn’t go over to their side. They couldn’t take your mind, Victor.” Victor looks downtrodden and says, “Would anybody believe that you and I are the same age and I’m even still a man?” Goffried wants Victor to accept a government scientific position, but Victor adds, “I am the last of the house of Frankenstein, but how much time do you think I have left? Every hour is a day out of my life, every month is a year. A month could see the end of my life. Goffried then asks why he needs the scientific equipment and why he disappears for days. “And now you need an atomic power unit,” Goffried wants to know why. Victor counters with, “Goffried, remind me to tell you sometime the story of the inquisitive commandant who …” (This line becomes a running gag throughout the movie!) At this point, the two men are interrupted by film crew members.

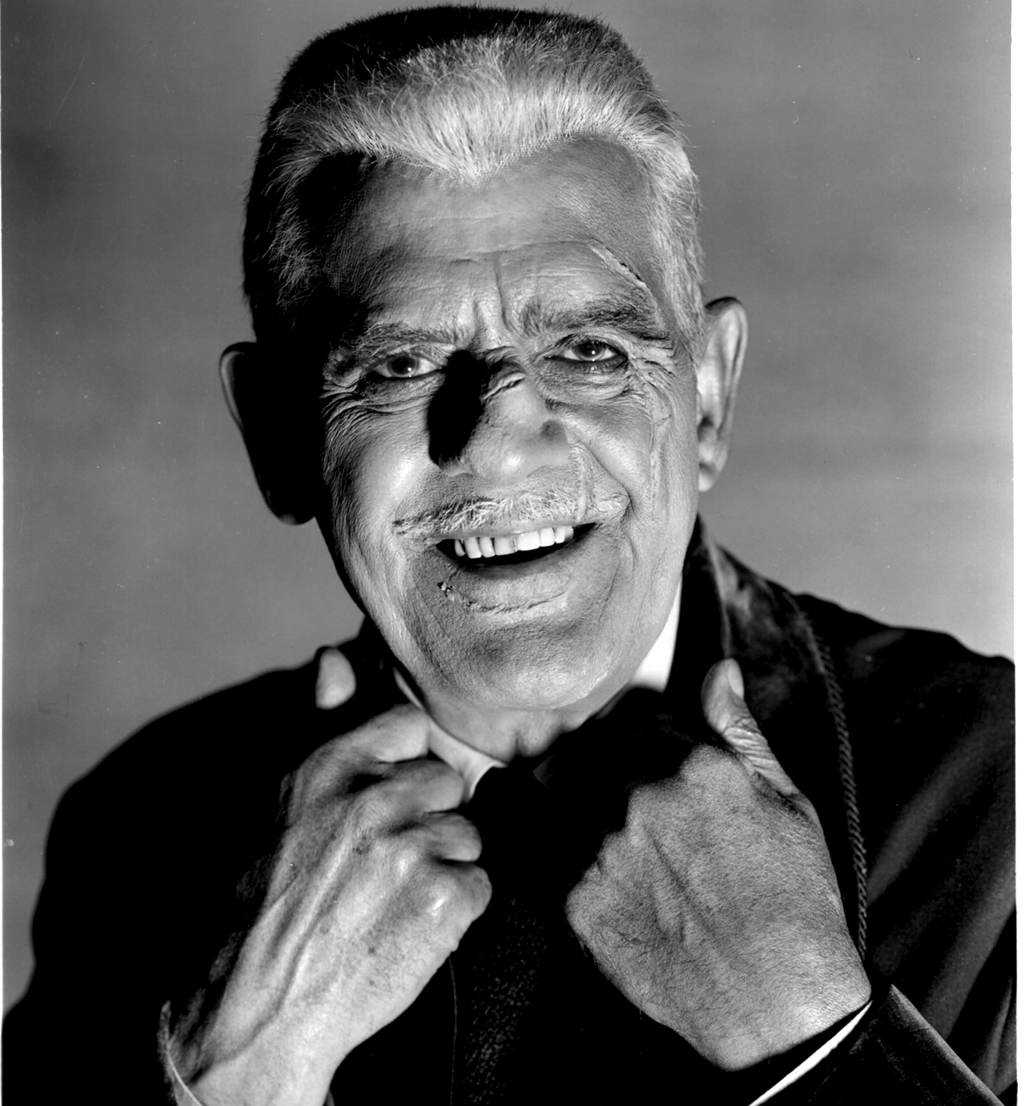

One of the movie's strengths is seeing icon Boris Karloff in another significant role. Instead of playing the monster, he plays his creator. And in such a schlocky movie, his initial performance, telling of his torture and perseverance, touches the heart. The manner and inflection with which he delivers the line about still being a man are riveting, and his cadence is right on. At the end of his conversation, when the movie crew bursts in, it reminds us that this is 1958, and Karloff’s star is still shining brightly, but it also reminds us of the class and talent he possesses for such a movie as this.

Another superb Karloff sequence occurs when he films his part of the movie, standing in front of the tomb of Richard Frankenstein, who lived 1702-1761, and was the original dabbler in recreating life. His crypt marker reads: “I, Frankenstein, began my work in the year 1740 A.D. with all good intentions and humane thoughts to the high purpose of probing the secrets of life itself—but with one end, the betterment of mankind,” And then in passionate rhetoric, he tries to explain all that his great-grandfather had struggled to achieve and how Richard became a victim.. “He created a living man! But to his horror, he discovered that his creation was a vicious, foul monster. His evil brain, but with one thought, to survive, he killed and killed again! And he became the image of the Devil incarnate. Then he realized what he had created; he must kill. However, because he was the creator, he dared not destroy it. Then, in his shot, he walks over to the covered creature and continues his soliloquy. Then Karloff raises a knife, and the figure beneath the sheet screams, as the director yells cut.

Karloff’s talent remains undiminished as he slowly and emotionally gives these lines life. It may only be a low-budget programmer, but Boris Karloff delivers his lines like Shakespeare wrote. The intensity, the cadence, that voice, and that stoic face create so much for the audience, and his “A” performance in a “B” movie creates something special for the spectator As grumpy Victor returns to his quarters, the script girl tells Jack the director that his lines were not in the script. He created them off the cuff. The movie crew cashes in on the horror of the Frankenstein legend, but Victor is trying to defend the good name of Frankenstein and exonerate his immediate ancestors.

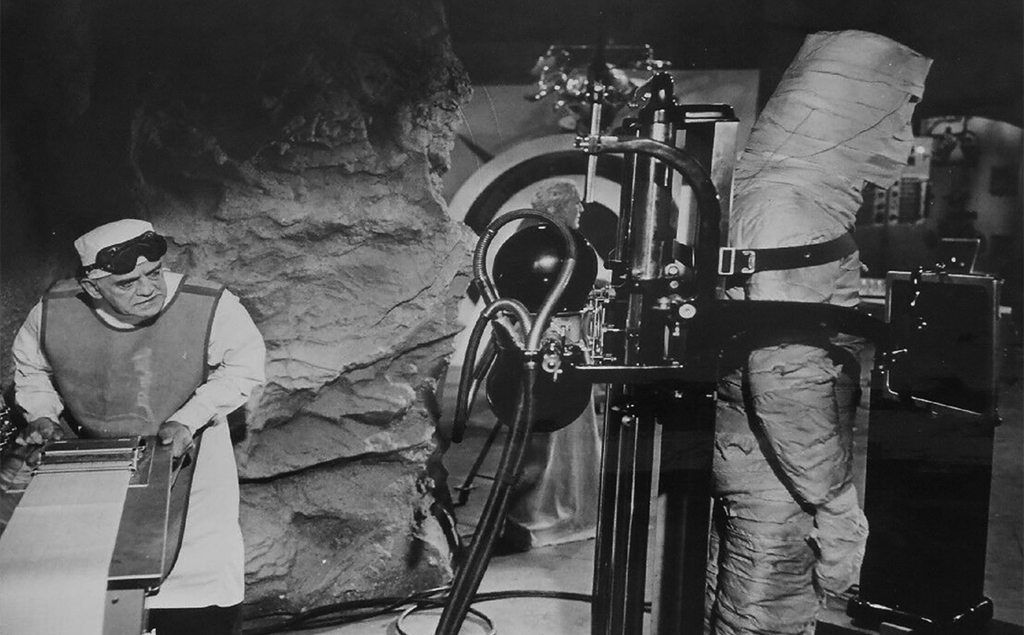

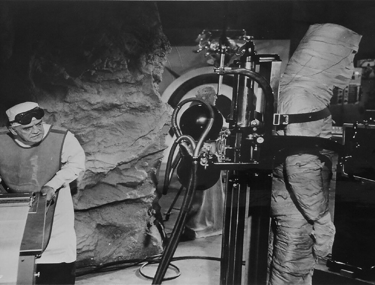

As sinister Paul Dunlap's music plays, Victor lights a candle, turns off all the lights as he looks around, and checks that he isn’t followed. He enters a room where he descends the staircase and walks down moldy corridors, and when he twists an angel’s head, a sarcophagus lid slides open. Once the monument is opened, it reveals another darkly lit staircase, on which Victor descends. Victor soon flips a switch to close the sarcophagus lid and continues his journey, finally arriving at his secret laboratory, a modernistic design that contrasts with his otherwise ancient castle. Victor uses a machine to spy on the film crew members while in their rooms.

This dialogue-free sequence is all mood, dark, and eerie. Background music accompanies spooky scenes of descending decrepit stairs, revealing that creepy stone coffins can move. The movie features several atmospheric sequences, demonstrating that director Howard Koch can immediately evoke a sense of malaise. The film may appeal to teenagers and the modern crowd. However, Koch and photographer Carl Guthrie find it easy to develop old-style horror.

While in his secret laboratory, Victor pushes buttons on an MRI-looking tunnel apparatus and out rolls a bandaged creature-to-be with an exposed skull, a giant assembled human. Victor shines a bright light on his creature and silently revels in the potential of creating life, just as his ancestors did before him. Examining the patchwork creature, he reports after cutting away bandages on one hand and exposing flesh and what looks to be staples near the wrist, “Sewn-on hands, both real and synthetic skin transplantation … pours open and normal … showing no deterioration … contemplating plastic surgery to remove old scar tissue … subject has maintained a perfect state of preservation … now waiting for final surgical step of trying to transplant vital organs, I’ll need to enact the atomic reactor to produce a rebirth.”

All this time, kindly servant Shuter (Norbert Schiller) has also been extinguishing lights and admiring the scarf one of the starlets gave him for his birthday. He accidentally turns the head of the angel, opening the sarcophagus, allowing him to descend the secret staircase. Victor intercepts him in an unlit lab, his face half lit in the darkness, registering regret. ”My dear Shuter, why did it have to be you?” Shuter is confused and does not realize the trouble he has stumbled upon. Victor intones in a very sinister voice, “A miracle, Shuter. Come here.” Victor turns on the light and is standing by the corpse, which Shuter finds unsettling and says, “No, you have opened its grave. You have brought the thing back!“ Shuter is almost in shock and is beckoned closer by Victor, brandishing surgical scissors. Victor rants, “He will live again. You will hear me, your brain will obey. What glory you will bring to the house of Frankenstein. You will live again. You will live again! Your brain will obey. No more pain, no more suffering. I’m doing you a favor, Shuter.” Then, Victor puts Shuter to sleep using the shiny scissors, hypnotizing him. Then Victor’s intense face begins to blur and fade out. Then we observe Shuter’s body side-by-side with the creature as Victor von Frankenstein cuts out Shuter’s heart. And soon his eyes (which he drops) and his brain.

In most Frankenstein movies, the pre-living creature is covered in gauze from head to foot: Frankenstein (1931), Bride of Frankenstein, Curse of Frankenstein (1957), and Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), among others. But after the recreation process, they are unwrapped and emerge as distinct monsters. A generic wrapped fiend is not a unique-looking and fleshed-out personality. Imagine if Boris Karloff played Frankenstein’s Monster completely covered in white gauze? Would it be as effective to play the sequence where he backs into the sunlight or stalks Elizabeth? Would Michael Gwynn be able to demonstrate the deterioration of his creation so proficiently if his body were hidden from the audience?

This is precisely what was done in Frankenstein 1970. The effectiveness of seeing a giant glazed monster on the slab piqued our interest in exploring the fully exposed monster. But once the creature goes on a murder spree, completely covered except for slits for eyes-to-be, it is a huge disappointment. Instead of a character and a fully scripted creature, we only get an undistinguished hulking monster without character or personality. He is all-powerful and deadly.

And what is particularly disappointing is that the monster shown in the opening scene was 100 times better than our giant mummy shown elsewhere. This new interpretation evolved from the Frankenstein Monster of the 1930s, re-imagined for the latest generation. Even without showing the front of his head, audiences immediately recognized this figure as Frankenstein’s Monster, complete with suit, clunky shoes, moving as if crippled, with frozen arms outstretched. That was an imaginative concept. But after that moody three and a half minute scene, the central concept used for Victor von Frankenstein’s creation was just that of a giant, generic fiend. Under all those wrappings might as well be a monster from outer space. Even the Hammer Frankenstein series had unique creations in every movie, and as we all know, a Frankenstein movie without an effective monster is a waste of time. It’s like Shakespeare’s Tragedies without compelling villains.

As bad as the movie crew is in private and communal rooms throughout the castle, some effective scenes sometimes occur once they shoot their movie. Take, for instance, when the movie photographer is filming a few publicity shots in front of Richard Frankenstein’s tomb, having Judy Stevens (Charlotte Austin) raise her skirt a little, for the cheesecake, “Let’s try one more shot. You back up in there, huh? Back up there … I want you to get back there. That’s it! Keep backing up, backing up. Keep going. Back up … keep going outside. I want you to make a clean entrance, all the way back. Judy ends up in a dark cul-de-sac and complains about the dark. ‘That’s the idea, I want you to come into the light. Back up !” As Judy backs up in silhouetted darkness, the monster's figure suddenly appears behind her, and Paul Dunlap’s music hits a stinger. But suddenly she is told to walk toward the photographer and escapes the creature’s clutches. But then. She is told to try it again and do it differently.

Judy backs up toward the Monsters’ outstretched arms as Judy emerges from the shadows and walks to the photographer again. The photographer frames shots as the music swells, trying to find good locations and starting to whistle, looking through the camera viewfinder. He encounters the gauze monster directly before him in the camera. He raises his camera to see the top of the creation and lowers it. Fear is all over his face. The Monster quickly advances because of his size as the man attempts to back away. But the fiend with outstretched arms catches him. Back at the lab, Victor is studying a pair of eyes and reluctantly discovers that the blood type is wrong for transplantation. But assistant Gotfried proves the perfect victim with the ideal set of eyes for the creation. As the monster emerges from the sarcophagus to confront the inquisitive financial advisor, we have just juxtaposed eyes with close-ups of Gotfried’s frozen face, which melts into another close-up of the monster sporting two new eyes.

THE VERDICT:

Frankenstein 1970 was relegated to Saturday matinee “B” double feature fare, mainly for kids and teens. The bland movie crew represents everything about the modern age and is meant to contrast with British pomposity, the Old World, and decaying castles with hidden entranceways. Except as the movie plays out, the Gothic nature soon overpowers the modern world. Sequences of the crew are cobwebbed between far more interesting sequences with Victor von Frankenstein, Gotfried, and Shuter. Even sporting an inferior Frankenstein creation, the creature is used for maximum suspense once Victor sends him on missions, and he interacts with the otherwise dull film crew. However, the most powerful superlative is the casting of Boris Karloff as Victor von Frankenstein. Too frail to portray the Monster, Karloff is depicted as playing the Frankenstein monster-creator. This ties the movie to the 1931 Frankenstein film and Karloff to the original series.

This is not a small supporting role filmed over a weekend, but a starring role that features Karloff in nearly every sequence. He effortlessly commands the screen with his iconic presence and delivery of the lines. Considering all his screen appearances from 1952 to 1968, this one may be his best performance. Admittedly, he delivers his lines somewhat over the top and sometimes comes off as melodramatic, but his performance is fun and can be watched repeatedly. His hesitancy, rhythm, and sarcasm are the work of a master, and this slimy performance is superb.

In addition to Boris Karloff's appearance, the film benefits from Carl Guthrie’s CinemaScope photography, Paul Dunlap’s score, and Howard Koch’s committed direction. In the movie’s final third, Koch creates some fantastic mood sequences by utilizing the lack of lighting to evoke genuine fright. How the otherwise generic fiend is employed in the hidden corridors of the castle’s shooting areas is inspired and cleverly executed for maximum chills. When the Monster is dying and is contrasted in size to the shorter Karloff, it always remains in my memory. The Monster appeared so large compared to Karloff. The final surprise unfolds as the Monster’s facial gauze is removed, revealing a shot of Karloff from The Invisible Ray (possibly) juxtaposed with Karloff’s voiceover, in which he states that he created the Monster in his image.

Frankenstein 1970 has its share of flaws and unnecessary bits, but what works is very effective and memorable. It is a film of perfect contrast, the old and the new, the tortured Victor and the scientist who echoes, “Shuter, why did it have to be you?” in a sad, sinister tone, and Gotfried, the best friend, the questioner, and the doubting Thomas. This film, which boasts major highs, must be watched for Boris Karloff’s intense performance in an otherwise flawed movie, making it ultimately worth the time and money.

BORIS KARLOFF AS VICTOR VON FRANKENSTEIN

THE INITIAL 3 MINUTES ARE THE BEST, DISPLAYING A RE-IMAGINING OF THE CLASSIC FRANKENSTEIN MONSTER.

IN CONTRAST, THE ACTUAL MONSTER USED IN THE FILM IS A GIANT, GAZE-WRAPPED ONE, LACKING PERSONALITY.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com