Charles Bronson and the Morality of Cannon Films Part Two

In three Cannon Films directed by J. Lee Thompson, Charles Bronson illustrates the morality created by this exploitation company

FILM NOIR/DARK CINEMA

written by Nicholas Anaz

6/10/202515 min read

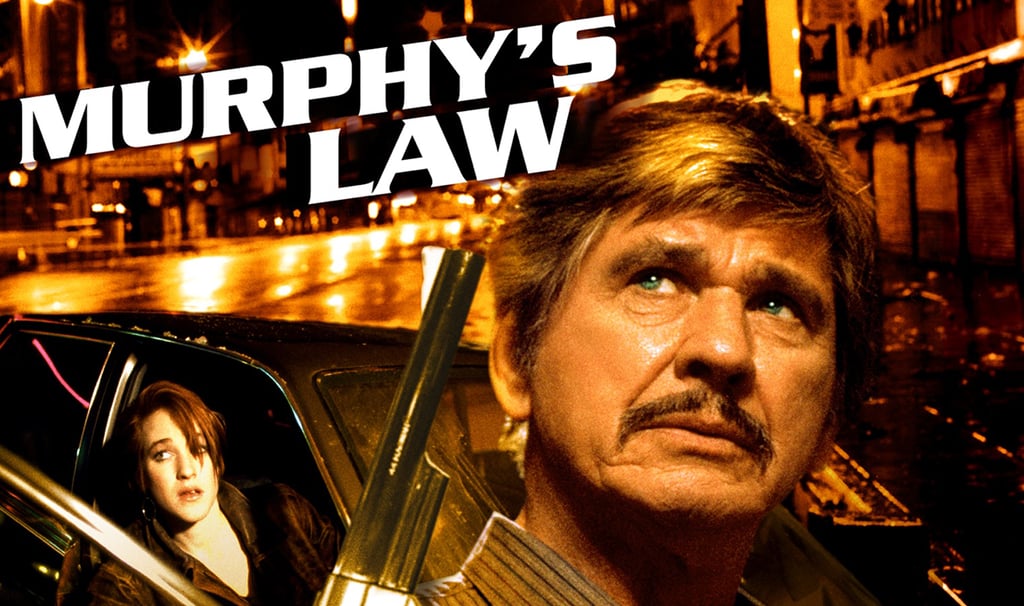

The conventional definition of Murphy’s Law is that anything that can go wrong will go wrong. That rule seems to apply to Detective Jack Murphy, the protagonist of the 1986 film Murphy’s Law. To begin with, Murphy’s wife has left him, and the impending divorce is plunging him into alcoholism. Adding insult to injury, she works as an exotic dancer in a sleazy strip joint. Furthermore, she is shacking up with the manager of the club. Murphy’s professional life is also in a downward spiral. He regularly arrives for work with a hangover, and his career appears jeopardized. But at least Murphy is aware of these problems. He doesn’t know that someone he sent to prison ten years earlier wants revenge. And this ex-con, a woman no less, is not only homicidal but is nuttier than a fruitcake.

However, Jack Murphy has his law. He hasn’t applied it lately because of his problems. But when a mobster threatens violence against him, the veteran cop expresses his law quite succinctly: “Don’t mess with Jack Murphy.” Since this is an R-rated movie, he doesn’t use the word “mess,” but it shouldn’t be too difficult to deduce the more explicit verb that he uses.

Charles Bronson plays Murphy, and this is the sixth movie that he made with director J. Lee Thompson. It is the second movie the duo made for Cannon Films, the second-tier studio known primarily for exploitation movies. Their first movie for Cannon was 10 to Midnight (1983). Though not a box office blockbuster, 10 to Midnight earned a nice profit and became immensely popular on home video. Furthermore, the movie proved that Bronson still had a considerable fan following. It also proved that Thompson could skillfully infuse even a Cannon film with genuine thrills and suspense. Bronson and Thompson reunited the following year to make The Evil That Men Do (1984) for TriStar, another exercise in violence but with a more expensive sheen than Cannon’s product usually displayed. They returned to Cannon for Murphy’s Law.

Murphy’s Law doesn’t have all of the exploitative elements of their first collaboration for the studio, such as extensive male and female nudity. However, Murph’s ex-wife comes pretty close to baring it all. It has its share of graphic violence, but not to the degree of the previous film. However, while 10 to Midnight also contains underlying social messages about contemporary justice, Murphy’s Law is unashamedly lacking in any message, social or otherwise. It also includes an element the previous film lacks, primarily a hefty dose of humor amidst the bloodletting. Most of the humor involves a string of inventive and often hilarious insults that Murphy’s unwilling partner in flight expresses toward him. Indeed, this film has more genuine humor than any previous Bronson-starring vehicle, not only due to the dialogue, some from the frequently expressionless star himself, but also to the unlikely pairing of the 65-year-old actor with a 21-year-old female cohort. (Yes, the 1973 Western From Noon Till Three is technically a comedy, but it isn’t funny, though not for lack of trying.)

Gail Morgan Hickman’s screenplay for Murphy’s Law contains nothing extraneous. The movie begins with a series of scenes that initially appear unrelated but will eventually converge. Upon completing his shopping, Detective Murphy surprises a young car thief, Arabella McGee, who is resilient enough to escape his capture. The next morning, Murphy is suffering from a hangover as he struggles to get out of bed and report for work. Upon viewing the body of a murdered woman, Murphy and his partner, Detective Art Penney, examine evidence which implicates Tony Vincenzo, the younger brother of crime boss Frank Vincenzo. That evening, a woman with a very determined and angry expression meets a private investigator named Cameron in a deserted park. The woman’s name is Joan Freeman, and Cameron has located the addresses of specific individuals for her. That same night, Murphy receives the final decree of his divorce. Then he gets a phone call from Freeman, who anonymously promises him intense suffering before she kills him.

At the police station the next day, it becomes clear that Murphy’s professional life is as disordered as his personal life. He and fellow cop Ed Reineke exhibit mutual antipathy while his superior, Lieutenant Nachman, rebukes him for his behavior and appearance. At least he seems to have a good relationship with Art Penney, and when they receive word that Tony Vincenzo is trying to leave the country, they race to the airport. The ensuing gunfight leaves Tony bullet-riddled and incites Frank Vincenzo to pledge retribution against Murphy. That night, Murphy visits the strip club where his disgust at seeing his nearly naked wife Jan bumping and grinding increases tension with her and her new partner, Carl. Thus, the stage is set for revenge, murder, and an extremely unlikely alliance. After Freeman frames Murphy for the murders of his ex-wife and her lover, his former colleagues arrest him and handcuff him to, of all people, Arabella McGee. This unfolding serves as an indication of the film’s momentum, as all of this occurs within the first thirty minutes, with the remainder of the story focusing on Murphy’s struggle to clear his name and find the real killer.

Murphy escapes from jail, which is a challenging task since he must take a resistant McGee with him. The disgraced cop hijacks a helicopter and escapes a hail of gunfire while being constantly heckled by a frenetic McGee. He gets sidetracked after crashing the copter into an illicit drug lab run by a biker gang, but he quickly proves to be a match for the potential rapists and killers. He seeks help from his former partner, Ben Wilkove, not realizing that Freeman has the disabled Wilkove in her sights for execution. Murphy initially suspects Frank Vincenzo of the murders but eliminates the mobster after reducing him to a pathetic, blubbering wimp. With Penney’s help, he eventually identifies Freeman as the killer. As he tries to find Freeman, who is determined to make him her final victim, he also has to avoid a vengeful Vincenzo, who is equally intent on killing him. If that isn’t enough stress for Murphy, he has to evade the police hunting him, including Reineke, who is delighted over Murphy’s plight. Eventually, Murphy must reluctantly accept that he needs the assistance of McGee, who surprisingly proves to be a resourceful ally.

J. Lee Thompson’s expertise is evident throughout the film. Murphy’s airport shootout with Tony Vincenzo is exciting and realistically violent. Thompson depicts Freeman’s murders with equal brutality but never gratuitously, beginning with Cameron and continuing with the judge who sentenced her and the therapist who was treating her. Freeman’s murder of Ben Wilkove is particularly fraught with tension as the director films the sequence from the viewpoint of the murderer. Thompson excels with the climactic confrontation at the famed Bradbury Building, a climax that pits Murphy against not only Freeman but Vincenzo, his hoods, and, much to his surprise, Reineke. Suspense and action combine to bring the film to a satisfying conclusion.

Interestingly, Hickman’s script doesn’t absolve Murphy of responsibility since it is clear that his actions facilitated the murder of his former wife and her lover. Freeman’s plan to frame Murphy for the double murder of Jan and Carl would have failed if not for his stalking of his ex-spouse. Moreover, he was clearly wasting his time because it was evident that Jan had contempt for him. But he stubbornly refused to accept his ex-wife’s rejection. If this refusal had not made him so careless and led to his excessive drinking, then he would probably have detected the fact that Freeman was stalking him while he was stalking his former wife. It should also be stated that Murphy is not a pleasant person. He has a nasty disposition and broods constantly. He tends to feel sorry for himself and is quick-tempered to the point of being violent.

The development of the relationship between this crotchety detective and the foul-mouthed thief who is young enough to be his granddaughter makes the movie entertaining. Initially, Murphy has nothing but scorn for McGee and treats her as he would any criminal. In turn, McGee attacks him continuously, initially physically and then verbally. He treats her with disdain even after they are no longer chained to one another. He hurts her feelings more than once, even after she risks her own safety to help him. He eventually detects her sensitivity beneath the bravado and begins to regret his behavior toward her. When he realizes that she is in danger of losing her life because of him, he learns how fond of her he has become. Wisely, there is no hint of a romance, which would have been absurd considering the age difference. The last scene depicts them in a prominent paternal or grand-paternal display of mutual affection and acceptance.

J. Lee Thompson was one of the few directors who could elicit a performance out of Charles Bronson, perhaps due to the frequency with which they worked together and their mutual respect. Michael Winner made six movies with the actor, and John Sturges, with four collaborations, also had some success. Bronson had to work with a director many times to develop the motivation to contribute something other than his presence to a movie. As Murphy, Bronson frequently displays emotion, including disgust toward his wife’s public disrobing, intense sorrow upon learning of Wilkove’s death, and explosive fury when McGee takes an arrow from Freeman’s crossbow. And he exhibits elation at the climactic confrontation when he says to Freeman: “Ladies first.” (Sorry, but it is necessary to see the movie to appreciate that line.)

As Arabella McGee, Kathleen Wilhoite is perfect, spewing her verbal insults with just the right amount of bluster, and yet eventually displaying vulnerability beneath the hard exterior. Carrie Snodgress is sadistically lethal as Joan Freeman, capably portraying her as a degenerate psychopath who genuinely enjoys her work. The supporting players perform efficiently, with Richard Romanus standing out as Vincenzo due to the sequence in which Murphy subjects him to Russian Roulette. The script does skimp on a few characterizations. Some of the participants, such as Dr. Lovell, are not fully developed, and the impact of her death would have been more alarming if Janet Maclachlan could have had more scenes. Regrettably, private detective Cameron bites the bullet early in the film because Lawrence Tierney is such an imposing presence in any movie. It seems that both of these characters are introduced just to be killed. But then again, that’s the kind of movie this is.

Murphy’s Law succeeds in being entertaining in an unpretentious way. There are no messages and the thrills are crude, but the movie gives Bronson’s fans what they want, despite the crudity or perhaps because of it. And it certainly displays more professionalism than the standard Canon offering. It may be forgettable, but it is engrossing and never dull. It is simply a solid and competent thriller. And that is probably all that Thompson, Bronson, and company intended it to be.

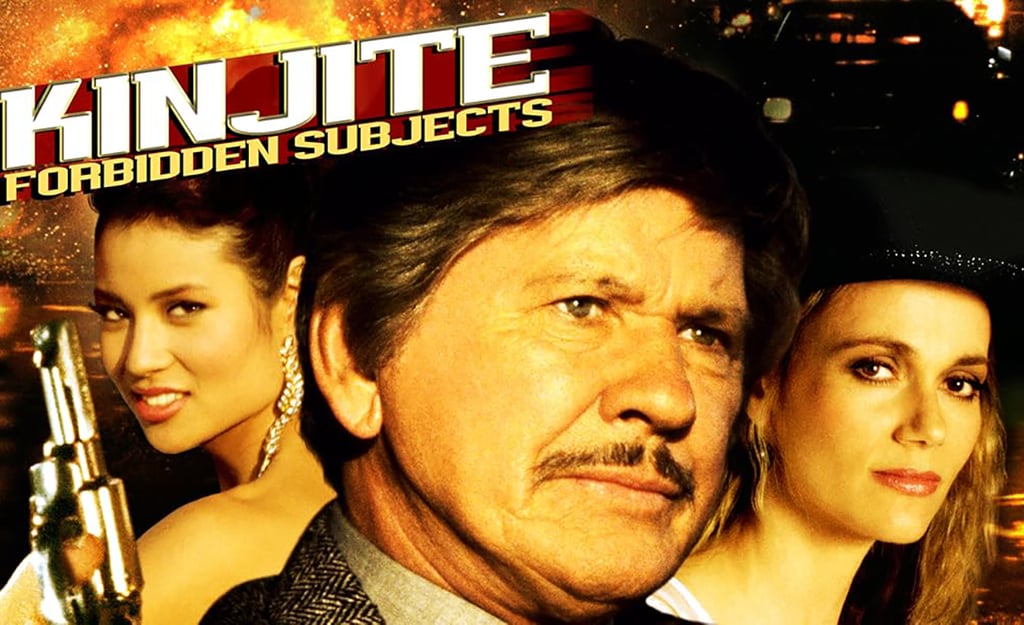

Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects, released in 1989, is notable for several reasons. It is the last of nine movies that Charles Bronson and J. Lee Thompson made together. It is the last movie that Thompson directed. It is the last of ten movies Bronson made with producer Pancho Kohner. It is the last movie Bronson made for Cannon Films. Finally, it is one of the most repugnant movies ever made by a major star and a renowned director. But that fact is also its main asset. This movie intends to disgust viewers deliberately.

Following Murphy’s Law (1986), Bronson and Thompson made Death Wish 4: The Crackdown (1987) and Messenger of Death (1988), both for Cannon. Neither of these two movies nor any of their previous collaborations approached the level of offensiveness that Kinjite does. The subject matter of Kinjite is child prostitution and the sexual exploitation of teenage girls. These are very disturbing themes which, in the hands of incompetent hacks, could have been the basis of a very sleazy film. Since this is a Cannon production, there are some sleazy elements, but because talented professionals were responsible for making this movie, the sleaze is kept to a minimum. Thus, while the topic is distasteful, the movie excludes explicit depictions of the most unsavory incidents.

The first part of Kinjite depicts two parallel stories highlighting the movie’s secondary theme of the contrast between two cultures. In Los Angeles, Lieutenant Crowe of the LAPD is determined to arrest Duke, a degenerate pimp who kidnaps and sexually enslaves adolescent girls. Crowe has a devoted wife and teenage daughter whose budding sexuality worries him because of his awareness of sexual predators rampant within his society. Due to the filth he has to contend with, he is consumed with rage and wants to leave the police force. In Tokyo, businessman Hiroshi Hada regularly engages in adultery and pornography, though he has a wife and two young daughters. Bored by Japan’s repressed culture, he is pleased when his supervisor informs him that he will be transferred to Los Angeles. Hada looks forward to the move because of Los Angeles’s reputation as a sexually permissive city.

Kinjite doesn’t waste any time in depicting its subject matter. During the main credits, a female undresses in apparent preparation for a sexual tryst with a male whose briefcase contains bondage paraphernalia. Lieutenant Crowe and his partner, Detective Eddie Rios, having witnessed Duke drive a teenage girl to the hotel, burst in and prevent the adult male from abusing the girl. The stupid fellow makes the mistake of resisting arrest, and Crowe proceeds to beat him to a pulp before administering poetic justice. Suffice it to say that the man’s screams echo throughout the hotel.

This incident infuriates Crowe, but since neither the prostitute nor the client will implicate Duke, he decides to enforce his brand of law. Taking Duke by surprise, Crowe forces the pimp to drive to a deserted setting where he angrily promises him that he will put him behind bars. Duke foolishly tries to bribe Crowe with his expensive watch. Consequently, Duke will probably have some difficulty digesting the timepiece. After Crowe emphasizes his point by burning Duke’s Cadillac, the pimp hysterically vows revenge upon the police officer.

Hada and his family arrive in Los Angeles, and the businessman resumes his adulterous ways, having no concern for his dejected wife or his daughters. As he boards a bus after a liaison, Hada recalls seeing a Japanese girl being molested on a subway and being unable to complain because of shame. He then attempts a similar act upon an American girl, but she reacts by screaming. Though he escapes arrest, his intended victim gives the police a description of the Oriental assailant whose face she will not forget. Her name is Rita Crowe. Her father is Lieutenant Crowe.

Crowe is livid upon hearing of the incident. He subsequently develops a hatred of Asians, especially Japanese, whose widespread presence in the city infuriates him. Meanwhile, Duke and his cohort, Lavonne, regularly cruise the town in search of potential victims. They know that areas around schools are filled with young students, and they are delighted when they see an Asiangirl in her early teens walking alone in a park. She is naïve and, upon being asked directions to her school, she gets into the car. This is the beginning of her horrifying nightmare. Her name is Fumiko Hada. Her father is Hiroshi Hada.

The two stories have now converged. The American father is a racist with uncontrollable outbursts of violence. The Japanese father is an adulterer with an uncontrollable sexual addiction. These two men meet because a child is missing. Crowe becomes determined to find her before she is harmed, while Hada pleads for her safe return. Both Crowe and Hada will have their hopes crushed because Fumiko’s abuse began immediately after her kidnapping. In Duke’s luxurious hotel suite, he raped the helpless girl and then turned her over to Lavonne. This was only the first step of their brutish domination over her. Once she was devoid of all hope, Duke started pimping her out to wealthy deviants and pedophiles.

Most audiences would not consider depicting such sordid themes to be entertainment. But the movie benefits from an incisive screenplay by Harold Nebenzal. Both Crowe and Hada have distinctly plausible personalities. Crowe’s bigotry is due not to intrinsic racism but to an excessive desire to protect his daughter. Hada’s sexual obsession is not owing to contempt for his wife but to excessive self-absorption. They are both emotionally disturbed. At least, Crowe realizes this and seeks counseling from his priest. But it will take a tragedy to make Hada aware of his problems. Duke, the cause of that tragedy, doesn’t have any psychological issues; he is just pure evil. Fiends like Duke exist in the real world, and the screenplay serves a purpose by presenting him in all of his malevolence.

Nevertheless, the movie could have emerged as tasteless sexploitation. Instead, director Thompson emphasizes the emotional content of the story. Crowe’s torment and Hada’s grief elicit sympathy at different stages of the film. However, Fumiko is the primary reason for the film’s emotional commitment. The scene in which a traumatized Fumiko appears out of the bedroom to appeal to Crowe and Rios is heartrending. It is also gratifying because she has finally been rescued. In appreciation, the Hadases visit the Crowes and give them a gift and a poem from Fumiko. On the surface, the meeting appears to be a joyous occasion for the two couples who happily celebrate Fumiko's return to her parents. Hada has learned to appreciate the value of his family. Crowe no longer has racist feelings.

But something beneath the surface occurs at this meeting. Rita Crowe recognizes Hada as the man who groped her, and Hada recognizes Rita as the girl whom he touched. Thompson highlights the scene’s significance by alternating close-ups of Rita with Hada. It is a gripping moment because it appears that a confrontation between the two fathers will happen just when the couple becomes acquainted. But Rita remains silent because she is aware of her father’s potential for violence, and she knows that her identification of Hada will lead to further violence. She inflicts her punishment on Hada by staring accusingly at him. From Hada’s expression, it is evident that he feels shame for his past behavior due to his daughter’s victimization. To the director’s credit, this scene with such unstated emotions is so powerful. But it is also deceptive because of its implication of an optimistic resolution.

Incidentally, some of Bronson’s fans complained that this scene represented a copout because the story seemed to be building to a violent confrontation between Crowe and Hada. But this would have been a typical Charles Bronson vengeful scene, the kind that his fans expected but also the kind that had become too familiar at this stage of his career. The peaceful resolution is different but appropriate because Hada is a changed man after enduring the ordeal of his daughter’s disappearance. He may deserve legal punishment for his offense, but such punishment would not be nearly as painful as he will soon experience.

Unfortunately, there is no happy ending. Crowe expresses foresight when he tells his wife that he wishes he could have found Fumiko sooner. He has previously witnessed the devastating effects of sex trafficking on children. And he will quickly learn that, as he feared, his rescue of the girl was too late. Fumiko has endured the tortures of hell and has been subjected to more suffering than any child should have to bear. She cannot forget the indignation and the horror. She cannot live with her shame. Fumiko sees no alternative but to take her own life. She ends her nightmare, but the nightmare for her parents will last for the rest of their lives.

Kinjite concerns an obscene subject, but it is not an obscene movie. Thompson’s innate sensitivity prevents him from depicting graphic depictions of Fumiko’s debasement. He only has to show Duke and Lavonne going into the bedroom to suggest the horrors inflicted upon the defenseless child. Thompson stresses the shocking impact of her abuse by focusing on her inconsolable appearance as Duke repeatedly prostitutes her. It is only necessary to see the enthusiastic expressions of the deviants who accept delivery of her from Duke to envision the extent of her continued abuse. Her expression speaks volumes because of the frailty beneath her stoic exterior. Only a child’s eyes can suggest such intense sorrow, thus eliciting from audiences unnerving discomfort at her helplessness.

The movie’s action scenes reveal another facet of Thompson’s skill. Crowe and Rios engage in a violent fist fight with some pornographers when they follow a false clue. This sequence serves no useful purpose other than to include some nudity (remember, this is a Cannon movie). Another more reliable tip leads to the capture of Lavonne, who will soon find himself wishing he had wings. However, the most exciting sequence is the climactic battle with Crowe and Rios against Duke and his thugs, which features a crane, a gunfight, and a fiery explosion. The sequence is unusual for a Bronson movie because Crowe doesn’t kill Duke as expected. He has an ulterior motive and once again inflicts poetic justice for a satisfying fade-out. But this last sequence doesn’t erase the film’s pervading sense of fatalism as represented by Fumiko’s ultimate destiny.

Once again, as in previous collaborations with Thompson, Charles Bronson provides his character with some depth. As Lieutenant Crowe, he exhibits genuine emotion when expressing fatherly concern, when displaying rage, and when confessing his sins. James Pax is equally fine as Hiroshi Hada, initially appearing as an egotistic libertine but eventually displaying extreme apprehension. The tears that he sheds over his daughter’s disappearance convert him into a compassionate character. As Duke, Juan Fernandez creates a chilling portrait of a depraved human monster. Amy Hathaway is appealing as Rita Crowe, but Kumiko Hayakawa is memorably haunting as Fumiko. All of the supporting actors contribute to the movie’s impact.

Ultimately, Kinjite is a somber film. The image of Fumiko lying down in her bed to die is difficult to forget. She exacted revenge upon Duke to some degree because her poem gave Crowe the clue he needed to find her defiler. Justice was served to the slimeball who destroyed her innocence but not until after her final act of expiation. Hada and his wife have lost their daughter forever. Crowe will resign, haunted by the fact that he couldn’t rescue Fumiko in time to save her.

“Kinjite,” translated from Japanese, means “forbidden subjects.” Child prostitution and slavery are truly the forbidden subjects that this movie realistically depicts. The film exposes the prevalence of an organized network of ruthless criminals who abduct underage girls, brutalize them into submission, and then sell them to perverted adults. Some people prefer not to acknowledge or even admit that this problem exists. Indeed, the mere discussion of the subject makes many people uncomfortable, which is why this movie is so distressing.

Kinjite: Forbidden Subjects is an extremely disturbing swan song for Charles Bronson and J. Lee Thompson.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com