Charles Bronson and the Morality of Cannon Films Part One

In three Cannon Films directed by J. Lee Thompson, Charles Bronson illustrates the morality created by this exploitation company

FILM NOIR/DARK CINEMA

written by Nicholas Anez

6/3/20259 min read

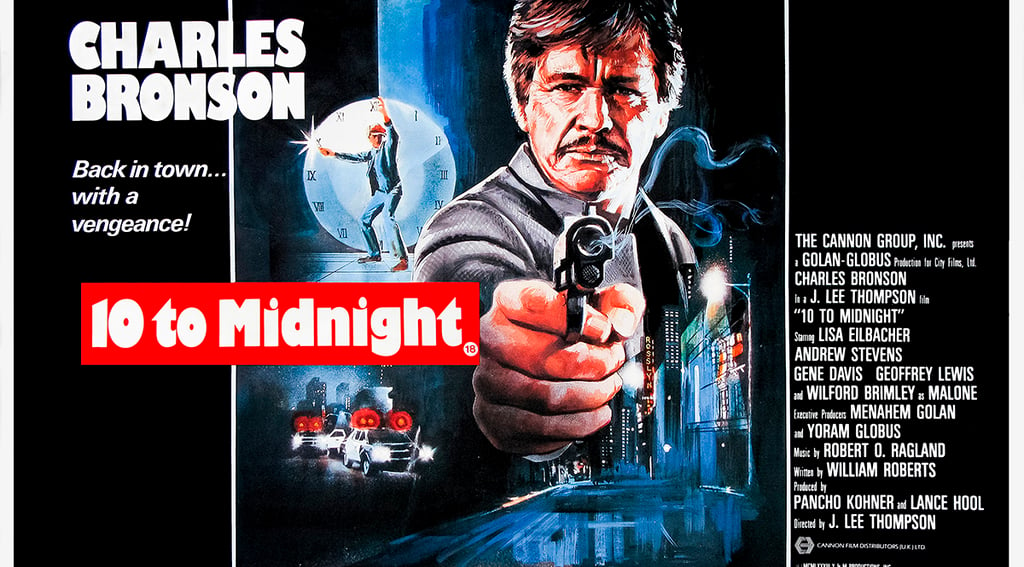

At this point, it would probably be helpful to state one indisputable fact. 10 to Midnight, the 1983 film directed by J. Lee Thompson and starring Charles Bronson, is trashy. To begin with, the story about a serial killer who slashes defenseless women is a subject matter that has served as the basis of numerous exploitative movies. More significantly, it contains all of the ingredients required to qualify as crude and tasteless entertainment, including female and male nudity, graphic violence, soft-core sex scenes, and obscene dialogue.

Upon the film’s release, it was surprising to see such notable talent as Thompson and Bronson participating in this type of movie. Thompson is the director of such acclaimed films as Tiger Bay (1959), The Guns of Navarone (1961), and Cape Fear (1962). He is also the past recipient of four BAFTA (British Academy of Film and Television Arts) nominations and one Academy Award nomination. Bronson is an actor who achieved international stardom in films such as "Rider on the Rain" (1970), "The Valachi Papers" (1972), and "Death Wish" (1974). In 1972, he received the Golden Globe Henrietta Award for World Film Favorite. Thus, the question arises as to why Thompson and Bronson collaborated on a movie with such tawdry elements. The answer is a simple one: Cannon Films.

Cannon Films was a minor studio that in the 1980s was known primarily for low-budget “B” movies appealing to undemanding audiences partial to redundant action, excessive violence, and gratuitous sex. Under the guidance of studio chiefs Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus since 1979, Cannon produced exploitation movies that were often relatively successful, particularly given their modest budgets. Golan and Globus elected to make movies that would hopefully be more financially profitable than their usual low-grade product, designed for quick playoffs and fast returns to expand their markets. Since acquiring major talents would be one step toward achieving this objective, they scored a major coup by signing Charles Bronson to a multi-film contract. Although his more recent films had been only moderately successful in the United States, Bronson was still a huge international box office draw. Bronson, in turn, brought to Cannon one of his favorite directors, J. Lee Thompson, with whom he had made three previous movies.

Bronson and Thompson began their partnership with St. Ives in 1976 for Warner Bros. and continued it with The White Buffalo in 1977 for United Artists and Caboblanco in 1980 for Embassy Pictures. 10 to Midnight is the first of five movies they would collaborate on for Cannon. The movie’s scenes of violence and sex were quite unexpected, considering the subtlety Thompson had previously employed in films covering a wide range of genres. However, Thompson had been directing since 1950, and by the 1980s, his incentive for working with Cannon may have been primarily to stay active in his advancing years. In addition, after three movies, Thompson and Bronson had developed a compatible working relationship. They also had the benefit of an insightful screenplay by William Roberts, who had co-written the scripts for such major films as The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Bridge at Remagen (1969); he was also the creator of the very wholesome television series, The Donna Reed Show (1958-1966). Roberts infused his screenplay with realistic characterizations and complex relationships, components not usually associated with Cannon product. Furthermore, it contains perceptive ideas about both official and unlawful aspects of criminal justice.

The protagonist of 10 to Midnight is Leo Kessler, a veteran Los Angeles homicide detective experiencing increasing frustration due to legal technicalities that he believes protect criminals and put innocent people in danger. This type of character resembles many other maverick cops that appeared on the big screen in the 1970s and 1980s. However, Kessler is radically different. He doesn’t just circumvent the law; he breaks it. He doesn’t just harass the man that he believes is guilty; he frames him. He isn’t just reprimanded for his actions; he loses his job. Above all, he differs in the consequences of his actions. If not for the illegal act that he committed, it is possible that three innocent young women would not have been viciously murdered.

The movie begins with a brutal double murder of a couple in a van in the woods. The murderer, Warren Stacy, is as naked as his victims, and he displays no mercy for the helpless woman begging for her life. Kessler is determined to catch this killer, not only because of the brutality of the murders but also because he knows the victim’s parents and has the unpleasant task of informing them of their daughter’s death. The murders also give him a pretext to try to mend fences with his estranged daughter, Laurie, a close friend of the victim. The estrangement is not Laurie’s fault since Kessler was so committed to his profession that he neglected his daughter as well as his deceased wife.

Laurie is a student nurse who shares a room with three other nursing students. She is neither hostile to her father nor overly friendly to him. She has been hurt too often by him in the past to so easily respond to his clumsy attempts to make up for his negligence. Despite her initial resistance to his overtures, she gradually softens because she wants her father in her life. Despite some initial hostility, she is also attracted to her father’s young subordinate, Paul McAnn. Meanwhile, McAnn finds it challenging to earn his superior’s respect, partly because He believes in doing his job by the book. However, Kessler and McAnn agree that Stacy is a prime suspect in the killings.

Warren Stacy is a young man with social and sexual inadequacies who murders women who reject him. He primped in front of a mirror in his bikini briefs, kept sex toys in his bathroom cabinet, and made obscene telephone calls to women, including Laurie Kessler. His inability to establish normal relationships with women provokes his homicidal attacks. Stacy is a psychopath who commits his murders in the nude primarily as a substitute for the sexual act; his positioning of the knife while committing the murders makes this quite clear. His secondary motive is to avoid leaving incriminating evidence at the crime scene. (The first criminal convictions based upon DNA evidence, which would be more difficult to eradicate, occurred in 1987, four years after the release of this movie.) He also cleverly manufactures solid alibis to ensure his continued manipulation of the justice system. And Stacy’s lawyer, Dave Dante, utilizes any legal loophole to free his client.

When it becomes apparent that Stacy is targeting Laurie, Kessler undertakes extreme measures. Kessler’s love for his daughter and his need to atone for his past neglect compels him to break the law. Since the justice system has stymied Kessler’s lawful efforts to stop the killer, he resorts to illegal measures. However, McAnn will not allow his mentor to violate due process. In one sense, McAnn emerges as the moral center of the film because he knows that while Kessler’s illicit actions would have put a suspected murderer behind bars, those same actions could also conceivably put an innocent person in prison. Moreover, while viewers of the film know that Stacy is the killer, Kessler doesn’t realize it, but only suspects it. Thus, it is unfair to blame McAnn for the ensuing bloodbath. If Kessler can break the law for what he believes is a justified reason, any person can break the law for any other reason, justified or otherwise.

Kessler loses his badge, but this doesn’t stop him from pursuing Stacy. Kessler’s subsequent persecution of Stacy has one objective: to force Stacy to implicate himself. But he underestimates Stacy, whose elaborate ploy with a prostitute deceives Kessler and sets up Laurie and her roommates as helpless victims for his bloodlust. Kessler makes the fatal mistake of believing he could make himself a potential victim of Stacy, not realizing that Stacy would unleash his fury upon his daughter and her roommates instead. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that though Kessler shares the blame for the carnage that climaxes the movie, the primary person responsible is, of course, the actual murderer.

The film ostensibly appears to validate Kessler’s illegal actions by showing the horrors of Stacy’s crimes as well as the failures of the judicial system, echoing Bronson’s most famous film, Death Wish. Script and direction seem to encourage empathy with Kessler’s decision to frame Stacy, as well as his subsequent harassment of the killer. However, when the film appears to be justifying Kessler’s vigilantism, it illustrates his inability to prevent a fatal chain of events that he has set in motion. It then depicts in shocking detail the unintended but horrifying consequences of his illicit behavior. Though Laurie survives Stacy’s frenzied butchery, her roommates suffer excruciating deaths. While Kessler can save his daughter, he realizes that she will never be safe from harm as long as Stacy remains alive. However, unlike Death Wish’s Paul Kersey, who perseveres through five films to continue enforcing his brand of personal justice, Leo Kessler will probably go to prison for executing Stacy in the presence of dozens of witnesses.

Charles Bronson gives one of his more effective performances as Leo Kessler. Bronson may have diminished his status by signing with Cannon, and, at this stage of his career, he relied too often on his established screen persona to sell tickets. But in this movie, he infuses passion into his characterization and displays a range of emotions that enhance his portrayal. In the intimate scenes with Laurie, he conveys the confusion of a man who wants to be a better father but is unsure of how to be one. On a lighter note, his reaction to finding Stacy’s sex toy is priceless, while his response to mistakenly choosing quiche is equally amusing. However, the climactic sequence in which his tangible fury is heartfelt and formidable makes his character memorable.

Another asset to the film is the presence of many talented supporting actors, whose skills help create believable characters instead of the usual cyphers that populate slasher films. Lisa Eilbacher conveys Laurie Kessler’s sensitivity beneath her surface resentment; she is imposing during the climactic sequence, during which she persuasively projects absolute terror. Andrew Stevens, as Paul McAnn, conveys the necessary idealism that contrasts with Kessler’s pragmatism. Geoffrey Lewis is so slimy as Dave Dante that his countenance exudes chicanery. Wilfred Brimley as Captain Malone and Robert F. Lyons as District Attorney Nathan Zager also add solid support. However, it is Gene Davis who excels in the role of Warren Stacy; his inflexible tone and impassive expression, when composed, contrast with his maniacal outbursts when enraged, creating a truly frightening degenerate.

Though J. Lee Thompson’s direction lacks the expertise of the films he made at the height of his career, it is more than competent. His staging of the action sequences is fascinating. He also convincingly depicts the development of warmth between Kessler and his daughter. Other sequences, including Kessler’s interactions with Stacy and the killer’s stalking of the nurses, are charged with tension. Most significantly, the movie doesn’t sink to the depths of typical slasher films. The opening double murder, along with the climactic carnage, as well as another murder within the story, are deceptive in their delineation. No nauseating, flesh-ripping, organ-exposing scenes are associated with films made by no-talent hacks. Audiences may believe they see more than what is shown, partly due to the skillful editing by Peter Lee Thompson, the director’s son.

Nevertheless, the climactic sequence depicting the terrified women being stalked, chased, and murdered by the blood-soaked killer is disturbing. There is something inherently objectionable about seeing the exposed women pleading for their lives to no avail. While such scenes thematically rationalize Kessler’s subsequent execution of Stacy, they are still markedly distasteful. Suppose Thompson had displayed his restraint in Cape Fear two decades earlier, 10 to Midnight would not register so high on the sleaze scale. However, Cannon Films of 1983 was not the same as Universal of 1962, and the 69-year-old J. Lee Thompson was not the 48-year-old J. Lee Thompson who directed the 1962 suspense classic. 10 to Midnight’s tawdriness is a product of its era, its studio, and a director who was no longer in his prime. But Thompson was never a hack, and his proficiency is evident amidst the trash.

Incidentally, Golan and Globus reportedly provided the movie with its unrelated title because, before production, they had pre-sold the title and Bronson to international distributors. The posters for the film attempt to give relevance to the title by showing a hazy figure against a clock in the background with his left hand pointed up to the number 12 and his right hand clutching a knife pointed toward the number 10. Thankfully, the Cannon chiefs didn’t call the movie The Naked Slasher.

10 to Midnight chillingly depicts a society at the mercy of unmitigated evil. The film’s nihilistic tone creates a sense of pessimism about the judicial system, which, since its release, has arguably become even less effective. Warren Stacy may be dead at the movie's end, but others like him thrive and are nourished in contemporary society.

End of Part One

KESSLER (CHARLES BRONSON), WITH THE CORONER, EXAMINE A CORPSE.

Get in touch

garysvehla509@gmail.com